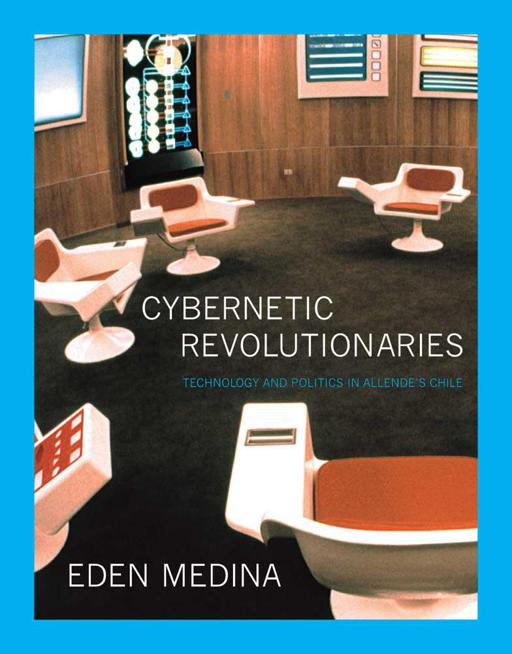

Cybernetic Revolutionaries

Cybernetic Revolutionaries

Technology and Politics in Allendes Chile

Eden Medina

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2011 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

For information about special quantity discounts, please email .

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Medina, Eden, 1976

Cybernetic revolutionaries : technology and politics in Allendes Chile / Eden Medina.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-262-01649-0 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-262-29738-7 (retail e-book)

1. ChileEconomic conditions19701973Case studies. 2. ChileEconomic conditions19701973Case studies. 3. Government business enterprisesComputer networksChile. 4. Government ownershipChile. 5. CyberneticsPolitical aspectsChile. I. Title.

JL2631.M43 2011

303.48'33098309047dc22

2011010109

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Cristian

Contents

Preface

I like to think that I came upon the history of Project Cybersyn, the 1970s Chilean computer network for economic management, because I was looking in the right place, and because it was a place that few in the history of technology had visited. I was a doctoral student at MIT, and I wanted to learn more about the history of computing in Latin America, the region of my birth. MIT has some of the best holdings in the country on the history of computing, but it soon became clear that material on Latin American computing was rather sparse. While I was digging in the stacks, bits and pieces of the story of Project Cybersyn caught my attention.

There wasnt much theretwo paragraphs and a footnote in one book. The book described the project using such phrases as cybernetic policy, decentralized computer scheme, and telex network operating in real-time, and linked it to a British cybernetician I had never heard of, Stafford Beer. This system was built in Chile and brought together in one project, political leaders, trade unionists, and technicians. Perhaps because I was reading about this curious cybernetic project while standing in one of the institutional birthplaces of cybernetics, the project took on special significance. Or maybe the story struck a chord because it so clearly brought together the social, political, and technological aspects of computing and did so in a Latin American setting. Whatever the reason, I was hooked and felt compelled to learn more about this curious system. Over the next ten years, the two paragraphs and a footnote that I had stumbled across evolved into this book on the history of Project Cybersyn.

The book began as an attempt to understand how countries outside the geographic, economic, and political centers of the world used computers. I was particularly interested in how Latin American experiences with computer technology differed from the well-known computer histories set in the United States, a difference I address in the pages that follow. But as I was writing this book, it gradually became clear that what I was writing was an empirical study of the complex relationship of technology and politics and the story of how a government used technology in innovative ways to advance the goals of its political project.

However, it was not just any political project. In 1970 Chile began an ambitious effort to bring about socialist change through peaceful, democratic means. It built on the reform efforts of the previous Chilean president, the Christian Democrat Eduardo Frei Montalva (19641970), who had tried to lessen social and economic inequality in Chile through increased foreign investment, import substitution industrialization, agrarian reform, and greater government ownership of Chiles copper mines. When the Socialist Salvador Allende became Chiles president in November 1970, he accelerated many of these changes and made them more profound. For example, he called for the government to bring the most important national industries under state control and developed policies to redistribute national wealth. He also stressed that socialist change would occur within the bounds of Chiles existing democratic institutions.

Nor was Project Cybersyn just any technological system. It was conceived as a real-time control system capable of collecting economic data throughout the nation, transmitting it to the government, and combining it in ways that could assist government decision-making. This was at a time when the U.S. ARPANET, the predecessor of the Internet, was still in its infancy, and the most technologically advanced nations of the developed world were trying to build large-scale real-time control systems. In fact, the Soviet Union had already tried and failed to build a national computer system for managing a planned economy. By 1970 Chile had approximately fifty computers installed in the government and the private sector, most of which were out of date, whereas approximately 48,000 general-purpose computers were installed in the United States at the time. However, those involved in Project Cybersyn believed that cybernetics, the interdisciplinary postwar science of communication and control, would allow them to create a cutting-edge system that used Chiles existing technological resources. This book seeks to explain how technology and politics came together in a Latin American context during a moment of structural change and why those involved in the creation of Project Cybersyn looked to computer and communications technologies as central to the making of such changes.

To tell this story I have relied upon a diverse range of source materials, including design drawings, newspaper articles, photographs, computer printouts, folksong lyrics, government publications, archived correspondence, and technical reports that I amassed from repositories in the United States, Britain, and Chile. I have made extensive use of the documents housed at the Stafford Beer Collection at Liverpool John Moores University in England, which holds sixteen boxes of papers relating to Beers work in Chile. This history also benefited from the personal archives of project participants Gui Bonsiepe, Roberto Caete, Ral Espejo, and Stafford Beer. How these documents survived is a story in its own right, and it shows that those involved with the project viewed it as a special accomplishment. I present part of that story in the pages that follow.

In addition, I used documents from a number of Chilean government agencies (including the State Development Corporation, the State Technology Institute, and the now-defunct National Computer Corporation); the library of the United Nations Economic Commission on Latin America in Santiago; the archives of the Catholic University of Chile; and the institutional holdings of IBM Chile. The rich holdings of the National Library in Santiago and the libraries at the University of Chile, the Catholic University of Chile, and the University of Santiago allowed me to supplement these primary sources with press accounts, other archived materials, and relevant secondary sources. A full list of consulted repositories appears in the bibliography.

I conducted more than fifty interviews in Chile, Argentina, Mexico, the United States, Canada, England, Portugal, and Germany between 2001 and 2010. Interview subjects included Cybersyn project participants, high-ranking members of the Allende and Frei governments, early members of the Chilean computer community, managers in Chilean factories, and members of the international cybernetics community, among others. Some interviews lasted thirty minutes, while others spanned two days. Some took place by means of extended e-mail correspondence. Unless otherwise noted, I have translated to English all the passages excerpted from Spanish-language interviews and written sources. Only a small number of the people interviewed for this project actually appear in the book, but all the conversations I had shaped my interpretation of this history.