ALSO BY SHASHI THAROOR

NON-FICTION

Pax Indica: India and the World of the 21st Century (2012)

Shadows Across the Playing Field: 60 Years of India-Pakistan Cricket (2009)

The Elephant, the Tiger, and the Cell Phone: Reflections on India in the 21st Century (2007)

Bookless in Baghdad (2005)

Nehru: The Invention of India (2003)

Kerala: God's Own Country (2002)

India: From Midnight to the Millennium and Beyond (1997)

Reasons of State (1982)

FICTION

Riot (2001)

The Five Dollar Smile and Other Stories (1993)

Show Business (1991)

The Great Indian Novel (1989)

ALEPH BOOK COMPANY

An independent publishing firm promoted by Rupa Publications India

First published in India in 2014 by

Aleph Book Company

7/16 Ansari Road, Daryaganj

New Delhi 110 002

Copyright Shashi Tharoor 2015

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from Aleph Book Company.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published.

As the Republic of India turns 65

This book is for my grandmother

Mundarath Jayasankini Amma

As she turns 98

And for my mother

Lily Tharoor

On her 78th birthday

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

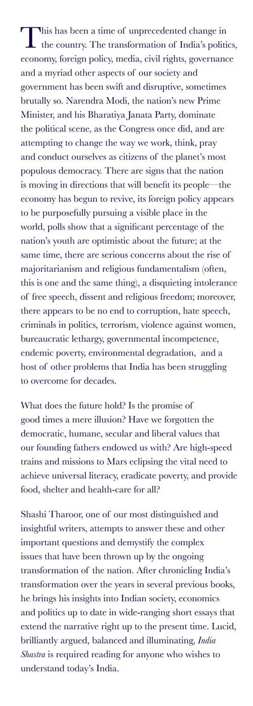

India Shastra is a collection of 100 articles and essays, some longish, some rather short, that seek to convey a portrait of contemporary India from the perspective of late 2014. Many of the pieces began life as columns in the media, but have been updated and expanded for this volume; some are adapted from speeches. Few have been left as they were originally written and delivered, since they are meant to be read at the dawn of 2015. The judgements in the book should stand as contemporary reflections of the India in which they are now being published.

With India Shastra I have concluded a de facto trilogy of works attempting to explore what makes my country what it is. India: From Midnight to the Millennium (1997), slightly revised and republished at the turn of the century as India: From Midnight to the Millennium and Beyond (2000), took in the broad sweep of Indias politics, economics, society and culture in its first fifty years of Independence. The Elephant, the Tiger and the Cellphone (2007) was a collection of various writings on the same themes, bringing the narrative of Indias transformation up to the sixtieth anniversary of Indias Independence. India Shastra (2015) updates the story with more recent writings, and takes into account the dramatic change in Indian politics today with the ascent to power of Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party. In a sense, the three books have evolved as my personal works of Smriti (memory), Shruti (hearing), and Shastra (thinking).

Section I, India Modi-fied, looks critically at a number of initiatives and actions of the new government in its first six months of existence. Section II, Modis India and the World, discusses the foreign policy actions of the current government. Section III, The Legacy, groups together a number of essays relating to the political inheritance received by the new government from its forerunners. Section IV, Ideas of India, goes beyond reaffirming my long-held (and often expressed) faith in Indias democratic pluralism to discuss a number of ideas relating to different aspects of Indian political life and the national ethos. Section V, The Pursuit of Excellence, covers a variety of areas in which India is striving, with varying degrees of success, to achieve quality outcomes. Section VI Issues of Contention, picks up a number of issues on which political opinion in contemporary India is sharply divided. Section VII, A Society in Flux, casts an eye on recent developments that point to changes in aspects of Indian life and society. And finally, Section VIII, India Beyond India, takes up a number of globally-relevant issues of interest and concern to India, but are not principally about India alone, except as part of the worldwide themes in which India is also implicated.

Taken together, the eight sections in this volume do not pretend to amount to a comprehensive portrait of India. Rather, they reflect my preoccupations relating to India over the past seven years, which happen to coincide with my return to my homeland after more than three decades abroad, first as a student and then as a career official of the United Nations. Though there is little by way of memoir or autobiographical reflection in it, except for a look back, in the final section, on my years at the United Nations, the book embodies many of the concerns that dominated my political life during this time. If there are glaring omissionscaste, for instance, hardly features, except in one essayit is not because these issues are not important, but because, for one reason or another, I did not write about them very much during this period (caste is, however, extensively discussed in India: From Midnight to the Millennium).

My basic thesis about India has remained consistent in these three books. It is a land of extraordinary pluralism and diversity, where political democracy is indispensable to national survival; a country of great economic potential held back by some of its own policies and practices, many of which are in the process of being re-examined and reinvented; and a lively, contentious and exciting society which is far removed from the timeless and unchanging land of well-worn clich. A Rip Kumar Winkle who had fallen asleep at the end of the Second World War seventy years ago would be unable to recognize the India of 2015. Everything has either changed dramatically or is in the process of changing: the nations politics, its economic preferences, its social assumptions, the relations amongst castes, the material and professional choices available in the country, the patterns and habits of daily life, and the intangible attitudes of Indians towards everything from religion to profit-making.

I am, I suppose, an old-fashioned liberal, one who believes in political liberty, social freedoms, minimal restrictions on economic activity, and a concern for social justice. This has tended to put me in a very small minority in India, where political opinion is divided between a left pledged to upholding socialism and state command of the economy, and a right defined principally by its adherence to religious and cultural nationalism rather than economic or political convictions. The one liberal political party that largely embodied my views, C. Rajagopalacharis Swatantra Party, disappeared in 1974, and it was only after the liberalization policies undertaken by the Congress in 1991 that I was able to find a congenial home there, albeit, on some issues, on its fringes. My political isolation in many respects has been compounded by the robustness of my views on foreign policy and national security, laid out in greatest detail in Pax Indica: India and the World of the 21st Century (2012). A liberal hawk is a rare bird anywhere, but particularly in an India whose social and economic pieties and peace-loving credentials were sanctified by the hallowed freedom movement led by Mahatma Gandhi.