2013

Lantern Books

128 Second Place

Brooklyn, NY 11231

www.lanternbooks.com

Copyright 2013 Martin Rowe

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of Lantern Books.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Rowe, Martin.

The elephants in the room : an excavation / Martin Rowe.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-59056-387-8 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-59056-388-5 (ebook)

1. Environmental protectionKenya. 2. Wildlife conservationKenya. 3. Humananimal relationshipsKenya. 4. KenyaHistory. 5. Great BritainColoniesAfrica, EastAdministration. 6. Sheldrick, Daphne, 1934 7. Maathai, Wangari. I. Title.

TD171.5.K4R69 2013

333.72096762dc23

2013018977

Permissions

Excerpts from Settlers, Childhood, Growing Up, and Married Life from Love, Life, and Elephants: An African Love Story by Dame Daphne Sheldrick. Copyright 2012 by Dame Daphne Sheldrick. Reprinted by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC. Excerpts from Unbowed: A Memoir by Wangari Muta Maathai, copyright 2006 by Wangari Muta Maathai used by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc. Any third party use of this material, outside of this publication, is prohibited. Interested parties must apply directly to Random House, Inc. for permission.

For Mia, who was there

Contents

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge the life and work of Professor Wangari Maathai and Dame Daphne Sheldrick, honor their dedication to the welfare and protection of those whom the powerful have long exploited and humiliated, and express my gratitude for their commitment to the preservation of the wild on this planet. It has also been a blessing to get to know Muta Mathai (whom I must thank for translating some Kiswahili); Waweru Mathai; and Wanjira Mathai, her husband Lars, and daughters Ruth and Elsa.

I want to extend my appreciation to Sangamithra Iyer for a conversation that stimulated my thinking about this project; to Judy Stone for her invaluable advice and work on the manuscript; and to Namulandah Florence for her many insights into the Kenyan context of Professor Maathai's life and political and environmental activities.

None of what I've written here would have been possible without the support and companionship of Mia MacDonald, who made me aware of the horrors that we inflict on nonhuman animals and brought to my attention Wangari Maathai and her work. In these, and countless other ways, she has immeasurably enriched my life and deepened my understanding of the many complexities of the world.

The Elephants in the Room is a contribution to HumanAnimal Studies (HAS) in general and to Lantern's series of books in HAS in particular, entitled {bio}graphies. This series explores the relationships between human and nonhuman animals through scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences viewed through the lens of autobiography and memoir, to deepen and complicate our perspectives on the other beings with whom we share the planet.

Author's Note

Changing fashions in orthography and pronunciation over the past century have meant that some words in The Elephants in the Room are spelled differently in quotations than in the main text. The African micronationality whom Willard Price refers to as the Watussi are more commonly known these days as the Tutsi, which is how I've chosen to name them. I've opted to use the more common spelling of Kikuyu rather than Gikuyu to describe one of the peoples and languages of the Central Highlands of Kenya. The Maasai people are often spelled using a double a, which is how I've decided to write the word; however, I've used the more common spelling of Masai Mara to delineate the region of Kenya known for the splendor of its wildlife. Likewise, with collective nouns I have used, with a few exceptions, the singular form (i.e. the Kikuyu) rather than the plural (i.e. the Kikuyus).

Dame Daphne Sheldrick's talk, given on May 8, 2012 at the American Museum of Natural History, including the slideshow, introductions, and the question-and-answer session, is available at the AMNH's YouTube site , then search for Sheldrick or (accessed June 18, 2013). You can read about the death of Lawrence Anthony, The Elephant Whisperer, at: (accessed June 18, 2013). M.R.

Introduction

Toying Architecturally with the Bones

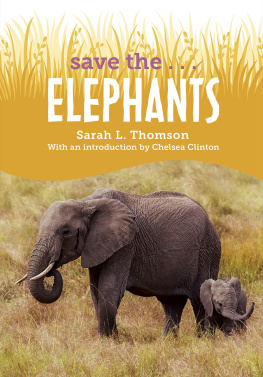

ON THE EVENING of May 3rd, 2012, my partner, Mia, and I took the elevator to the fourth floor of the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. We'd been invited to a soire to celebrate the publication of Love, Life, and Elephants, a memoir by Dame Daphne Sheldrick, matriarch of the David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust, which looks after orphaned baby elephants and rhinoceroses at its compound at the edge of Nairobi National Park in Kenya. The Trust rehabilitates the elephants and rhinos over many years before it releases them into Tsavo National Park, also in Kenya.

The elevator doors opened and we turned right, into the Paul & Irma Milstein Hall of Advanced Mammals in the Lila Acheson Wallace Wing of Mammals and Their Extinct Relatives, where we were immediately confronted by the skeletons of three proboscideansmammut americanum, gomphotherium, and mammuthus. As you might imagine, to walk past these animals on the way to a fundraiser for preserving their distant elephantine descendants presented a certain cognitive dissonance. Nor were these the only bone-houses on display. We encountered, assembled in neatly arranged glass cases, the ancient precursors of camels, pigs, rhinos, tapirs, tigers, sloths, marmots, armadillos, deer, and horses. According to panels near the entryway, these creatures had vanished between 30,000 and 10,000 years ago, likely from two main causes, both of which tolled a familiar, depressing bell. The animals had either died at the spear points of our predecessors, who during the Paleolithic era had spread in sizable numbers throughout the continents, or they'd been unable to adapt to the warmer weather that signaled the end of the Ice Age and had died out.

The living mammals among us were herded into a circular room that overlooked Central Park, in the turret named after the late socialite and philanthropist Brooke Astor, third wife of Vincent, one of whose extinct relatives had once been the richest man in America. John Jacob Astor (17631848) had made his fortune in real estate and through the trafficking of the fur of beavers, whose ancestors we'd also strolled past. Attendees at this social occasion feasted on members of the families phasianidae (chickens) and penaeidae (shrimp), spring rolls, and assorted nuts. The Trust's U.S. board members greeted us and the actress Kristin Davis told us of her connection to Daphne Sheldrick, and how inspired she'd been by her work.

The chair of the U.S. board invited the guest of honora stocky, white-haired woman in her late seventiesto the dais. In clipped, flatly enunciated tones, Dame Daphne (she'd been knighted in 2006) thanked us for coming, marveled at how long it had taken for her to write her book, and expressed her hope that we'd continue our support of the Trust. After some more grazing, the assembly then migrated to the museum's IMAX Theater, where Dame Daphne narrated a slideshow that illustrated her life in her native Kenya, and the many species of animals with which she'd been privileged to spend time over the decades. Following her address, Dame Daphne accepted questions, and then moved from the theater to a table, where a long line of people waited for her to sign their copies of

Next page