BATTLING AND MANAGING DISEASE

HEALTH AND DISEASE IN SOCIETY

BATTLING AND MANAGING DISEASE

EDITED BY KARA ROGERS, SENIOR EDITOR, BIOMEDICAL SCIENCES

Published in 2011 by Britannica Educational Publishing

(a trademark of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.)

in association with Rosen Educational Services, LLC

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010.

Copyright 2011 Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopdia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved.

Rosen Educational Services materials copyright 2011 Rosen Educational Services, LLC.

All rights reserved.

Distributed exclusively by Rosen Educational Services.

For a listing of additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, call toll free (800) 237-9932.

First Edition

Britannica Educational Publishing

Michael I. Levy: Executive Editor

J.E. Luebering: Senior Manager

Marilyn L. Barton: Senior Coordinator, Production Control

Steven Bosco: Director, Editorial Technologies

Lisa S. Braucher: Senior Producer and Data Editor

Yvette Charboneau: Senior Copy Editor

Kathy Nakamura: Manager, Media Acquisition

Kara Rogers: Senior Editor, Biomedical Sciences

Rosen Educational Services

Alexandra Hanson-Harding: Editor

Nelson S: Art Director

Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager

Nicole Russo: Designer

Matthew Cauli: Cover Design

Introduction by Monique Vescia

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Battling and managing disease / edited by Kara Rogers.1st ed.

p.; cm.(Health and disease in society)

In association with Britannica Educational Publishing, Rosen Educational Services.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61530-484-4 (eBook)

1. Public health--Popular works. 2. Medicine, Popular. I. Rogers, Kara. II. Series: Health and disease in society.

[DNLM: 1. Delivery of Health Care. 2. Diseasehistory. 3. Cross-Cultural Comparison. 4.

Developed Countries. 5. Developing Countries. 6. Socioeconomic Factors. W 84.1 B336

2011]

RA431.B38 2011

362.1dc22

2010023229

On the cover: The bacterium Campylobacter jejuni, shown here in petri dishes, causes gastroenteritis. Henrik Sorensen/Stone/Getty Images

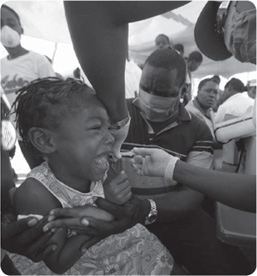

On pages : A nurse prepares a vaccine against the A(H1N1) (swine flu) virus at a high school in the western French town of Quimper on November 25, 2009. Fred Tanneu/AFP/Getty Images

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

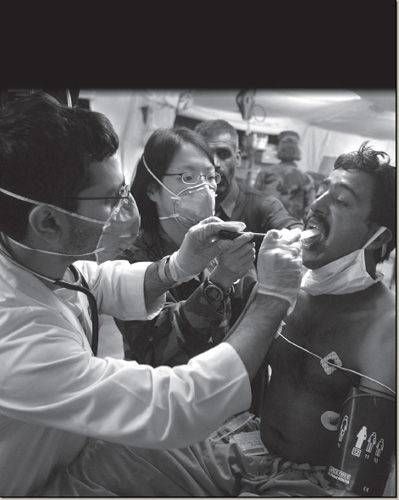

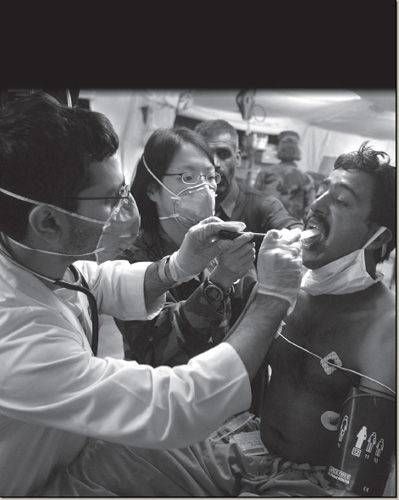

A diphtheria patient is examined by two American doctors at a Mobile Army Sugical Hospital (MASH) in Muzaffarabad, Pakistan in 2005. The disease spread quickly after a devastating earthquake in the region. Paula Bronstein/Getty Images

T oday it is widely known that certain diseases are contagious, whereas others are not, and that a specific malady may be a result of where an individual lives or works, of what a person eats or drinks, or of the genes he or she inherited. This understanding of illness first emerged, along with other advances in human culture, in ancient Greece, when people began to formulate scientific theories about the origins of disease. One of the first to recognize that air, water, and the environment can all be sources of sickness was Greek physician Hippocrates, who lived in the 5th to 4th centuries BCE.

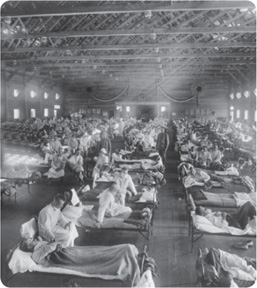

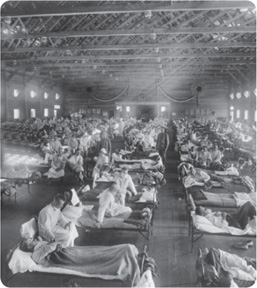

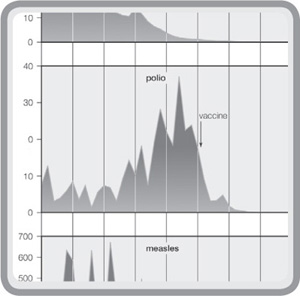

The people of the ancient world and the Middle Ages suffered periodically from epidemics of highly contagious illnesses, such as leprosy and smallpox, which afflicted large portions of Earths population. Today, with the benefit of advanced medical knowledge and systems of public health care, the devastation seems unimaginable. But centuries ago, there was little knowledge of how to stop contagion. Some of the first advancements included the establishment of hospitals, the development of quarantine (isolation) for infected patients, and the improvement of sanitation.

In the 16th and 17th centuries an understanding of microorganisms and their role in disease started to take shape. Also during this period, some of the first comprehensive statistical records on public health appeared. An Englishman named John Graunt began keeping death records of Londons population. Graunts statistics, published in 1662, showed that city dwellers had higher mortality rates than rural people. Such statistics would eventually form the basis of epidemiology, the study of disease in human populations.

As important as they were, these scientific advances would not significantly improve the health and welfare of the general population until public health policies and services could be established. So, while people recognized that a countrys productiveness depended upon the good health of its citizens, the foundations of large-scale public health systems still remained to be laid. Public pressure and political will eventually forced these developments into motion.

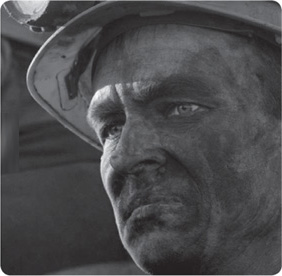

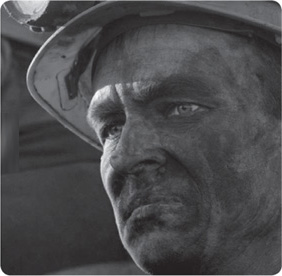

The Industrial Revolution prompted a surge in urban populations, as people moved from rural areas into cities where jobs were plentiful. Increasing numbers of workers (many of them children) laboured for long hours in coal-burning factories. These work conditions contributed to a range of health problems, including respiratory ailments such as tuberculosis (TB) and industrial accidents. Inadequate housing, poor nutrition, lack of sanitation, and the coal dust that fouled the air further undermined workers health. Despite efforts by reformers and humanitarians to educate people about disease transmission, illnesses swept through the slums.

Next page