Copyright 1994 by Smithsonian Institution.

All rights reserved.

Designed by Kathleen Sims.

Edited by Lorraine Atherton.

Production editing by Rebecca Browning.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Jenkins, Virginia Scott.

The lawn. A history of an American obsession /

Virginia Scott Jenkins,

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references ().

ISBN 978-1-56098-406-1

eBook ISBN:978-1-58834-516-5

1. LawnsUnited StatesHistory. I. Title.

SB433.J46 1994

716dc20 93-28003

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available.

This book contains references to various commercial organizations and products. The author has made every effort to identify company and product designations, some of which may be registered trademarks, and to distinguish them with initial capital letters. The appearance of any such commercial names in this book constitutes neither endorsement nor criticism on the part of the Smithsonian Institution.

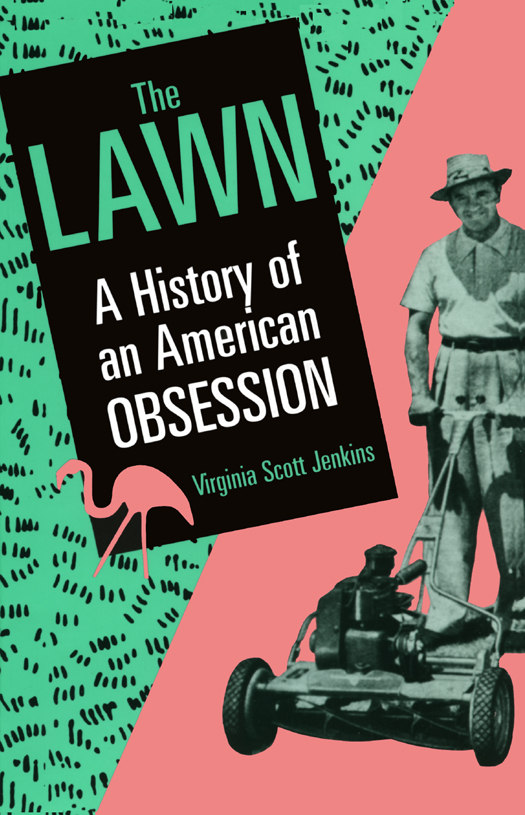

The cover image of Sam Snead pushing a 1951 Toro lawn mower is taken from a Toro advertisement that appeared in the March 1951 issue of Flower Grower magazine and is used here with permission from the Toro Company.

For permission to reproduce illustrations appearing in this book, please correspond directly with the owners of the works, as listed in the captions. Smithsonian Books does not retain reproduction rights for these illustrations individually or maintain a file of addresses for illustration sources.

v3.1

For my mother, Jane Lyman White, and my husband, Thomas A. Anastasio, with love and thanks.

Both, in their way, made this book possible.

Contents

PART ONE

Americans Adopt the Front-Lawn Aesthetic

PART TWO

The Democratization of the Lawn

Acknowledgments

The staff of the Archives Center of the Museum of American History and Technology of the Smithsonian Institution, the Division of Domestic Life, Terry Sharer and Pete Daniel of the Division of Agriculture, and Charlie McGovern in the Division of Community Life have all been very helpful in this project. Susan R. Gurney, chief librarian of the Horticulture Division of the Smithsonian Institution, provided seed catalogs, gardening books, and information on the Philadelphia Centennial.

The Library of Congress was a rich resource for popular magazines. I would particularly like to thank Delores Moyano Martin for her assistance when it came time to photograph the advertisements. I am also grateful to Mattingly Eisner for the loan of his photographic equipment.

Janet Segal, librarian at the Golf House Museum and Library, U.S. Golf Association, Far Hills, New Jersey, made material on the USGA and the USDA available. Mrs. Herbert H. Hendricks of the Garden Club of America and Mrs. Monica Freeman, library secretary of the Garden Club of America Library in New York, were very interested in my project and made me welcome. The U.S. Department of Agriculture Library, Beltsville, Maryland, was an important source of material, and the staff was always helpful. Kevin Morris, of the National Turf-grass Evaluation Program, and Mieki ONeill, grass pathologist with the Agriculture Research Service in Belts ville, Maryland, were very generous in making their files available to me.

Many thanks to my mentors and advisors at the George Washington University, Bernard M. Mergen, Barbara G. Carson, Clarence C. Mondale, Howard F. Gillette, Jr., and Donald E. Vermeer, for their reading, suggestions, criticism, and support for this project. Janet King and Susan Wolfe also read chapters of this book, and their suggestions were very helpful. Peter Bent provided important information on popular music and American culture.

I would also like to thank Wendy Frieze, Angela Leonard, Andrea Foster, Jacqueline McGlade, and Dorothy Pennino for their friendship and support as we faced the creative process together.

Mark Hirsch, acquisitions editor at the Smithsonian Institution Press, has never flagged in his enthusiastic support for this project as it grew from a doctoral thesis into a book. He helped make the whole process enjoyable.

Finally, I would like to thank my husband, Tom Anastasio, for his continuing interest, editorial advice, and technical assistance. Without him, there would have been no Lawn.

Introduction

I grew up in a house in Connecticut with a front lawn, but the American aesthetic of the lawn as a green velvety carpet was not part of my childhood. That was possibly because lawns in the United States are mens work. My mother (widowed when I was six years old) was far more interested in her garden than in the grass in the front yard (I hesitate to call it a lawn). She occasionally responded to a perceived need to do something about it, perhaps because of the advertising messages of the lawn-care industry, horticultural advice in popular magazines, or the example of other front lawns on our street. When that happened, she hired two boys who lived across the street to cut our grass. One year my mother paid me and my sister a penny for every ten dandelions that we dug out of the back yard. I can still remember the blisters I got from digging with a kitchen knife.

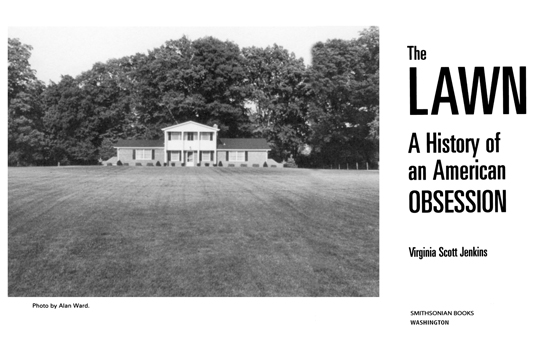

My mother did not share the aesthetic that a velvety green carpet was necessary in front of our house. Nor has the aesthetic been important to me as an adult. I can remember the first time I visited Ohio and saw people riding mowers over acres of front lawn. I was amazed and wanted to know why they were willing to spend so much time, energy, and money on what appeared to be unused space. At our home in Maryland, my husband and I have widened the flower beds and planted ground cover, making our front lawn smaller each year. We did away with the grass in our back yard altogether.

However, we are not typical in that respect. American homeowners spend billions of dollars plus untold hours and energy on their front lawns every year. An entire lawn-care industry has developed that employs thousands of people. As I pondered these curious facts, I began to wonder about the history of our obsession with the front lawn. Why do Americans have front lawns when people in other countries have front gardens or build their homes directly on the street with interior courtyard gardens? What do front lawns tell us about American culture? Why is the residential landscape similar in all parts of the country? Why do some homeowners spend so much time, money, and energy on maintaining a front lawn that they do not use? How has the residential landscape changed, and what changes will occur in the future? This book is an exploration of the American front lawn and of the changes in our landscape and ecology as a result of the choices made by individual homeowners.

As I began my research, I discovered that before the Civil War very few Americans had lawns at all. Until the mid-nineteenth century, the houses in many American towns were built close to the street with perhaps a small, fenced front garden. On farms, houses and farm buildings were surrounded by pasture, fields, or gardens and a bare, packed dirt farmyard. Currier and Ives prints show farmhouses with such yards. A painting by Winslow Homer (18361910) with the title