UNDERSTANDING

CLASS

ERIK OLIN WRIGHT

This eBook is licensed

For my brother, Woody Wright,

and father-in-law, Robert L. Kahn,

with love and admiration

This eBook is licensed

First published by Verso 2015

Erik Olin Wright 2015

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78168-945-5 (PB)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78168-920-2 (HC)

eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-921-9 (US)

eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-922-6 (UK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wright, Erik Olin.

Understanding class / Erik Olin Wright.

pages cm

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-78168-945-5 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-78168-920-2 (hardback) ISBN 978-1-78168-921-9 (ebk)

1. Social classes. 2. Marxian school of sociology. I. Title.

HT609.W7134 2015

305.5dc23

2015012843

Typeset in Sabon by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh, Scotland

Printed in the US by Maple Press

This eBook is licensed

CONTENTS

This eBook is licensed

The essays assembled in this book were written between 1995 and 2015. They involve three agendas: interrogating the approaches to class analysis of specific writers working in a variety of theoretical traditions; developing general frameworks of class analysis that can help integrate the insights of different theoretical traditions; and analyzing the problem of class conflict and class compromise in contemporary capitalism.

Most of the chapters in this book are concerned with the first of these agendas, exploring in detail theoretical issues in the work of a range of writers who specify the concept of class in different ways: Max Weber, Charles Tilly, Aage Srensen, Michael Mann, David Grusky and Kim Weeden, Thomas Piketty, Jan Pakulski and Malcolm Waters, and Guy Standing. My own approach to class is firmly embedded in the Marxist tradition, while none of these writers adopts a Marxist approach and some are overtly hostile to Marxism. Often in encounters between Marxist and non-Marxist approaches to some problem the basic stance is one of combat, each side trying to defeat the arguments of the other. While there may be circumstances in intellectual debates where vanquishing an opponent is appropriate, in these essays my goal is to figure out what is most useful and interesting rather than mainly to point out what is wrong with a particular theorists work. One might call this virtue-centered critique rather than flaw-centered critique. Of course, it is necessary to clarify gaps and silences in particular bodies of work, to illuminate salient differences between approaches, and sometimes to identify more serious theoretical flaws. But all of this is still in the service of clarifying and appropriating what is valuable rather than simply discrediting the ideas of rival approaches.

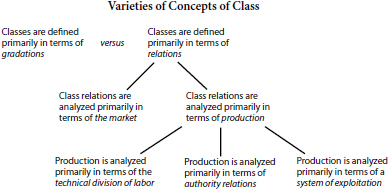

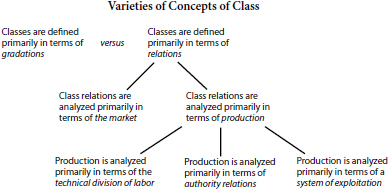

It is one thing to recognize that there are valuable insights to be appropriated from even hostile theoretical traditions; it is another to try to systematically integrate those insights into a broader framework. This is the second task of this bookproposing general strategies for integrating key ideas from Marxist and non-Marxist currents of class analysis. My approach to accomplishing this comes out of a longstanding preoccupation in my work with constructing conceptual typologies as a way of clarifying the theoretical differences between my arguments and those of others grappling with the same problems. For example, in my early empirical work on class structure I used a typology in the form of a branching diagram of alternative ways of defining class as a way of identifying the specificity of the Marxist concept.

Source: Erik Olin Wright, Class Structure and Income Determination, New York: Academic Press, 1979, p. 5.

My initial purpose in constructing this kind of typology was to draw clear lines of demarcation between alternative theories and concepts and then argue for the virtue of my preferred option. More recently, however, it has become clear to me that there is an alternative way of using such typologies. To the extent that a typology of theories identifies the distinct mechanisms that are the focus of different theories, it might be possible to integrate at least some of the different approaches to class into a more general framework of analysis organized around the interconnections among these different mechanisms. Rather than mainly see alternative approaches as competing with each other, perhaps they could potentially be seen as complementary.

My first effort at doing this was the edited book, Approaches to Class Analysis (Cambridge University Press, 2005). The book included essays by six sociologists working within different theoretical approaches to class analysis. Each contributor was instructed to write an essay elaborating the theoretical foundations of a particular approach to class analysis. The title of the concluding chapter posed the question If Class Is the Answer, What Is the Question? The basic idea was that different strands of class analysis were anchored in different kinds of questions, and this helped explain why the concept of class was defined in different ways. The last sentence of the book loosely evoked Marxs famous passage about a society without class divisions in which it was possible to hunt in the morning, to fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticize after dinner: One can be a Weberian for the study of class mobility, a Bourdieusian for the study of class determinants of lifestyles, and a Marxian for the critique of capitalism.

The next logical step was to try to integrate the mechanisms connected to these different questions into a more comprehensive framework. Three chapters in this book try to do this in different ways. , From Grand Paradigm Battles to Pragmatist Realism, originally published in 2009 in New Left Review, constructs an integrative model for class analysis by arguing that the different broad traditions of class analysis are anchored in three different clusters of causal mechanisms: stratification approaches to class define class in terms of individual attributes and conditions; Weberian approaches define class in terms of a variety of mechanisms of opportunity hoarding; and Marxist approaches define class in terms of mechanisms of exploitation and domination. Each of these causal mechanisms plays a key role in particular streams of causal processes. The task of the essay was to clarify these focal mechanisms and then try to integrate them into a broader explanatory model of class analysis. The key device of this integration was a series of diagrams connecting the micro-level of class effects tied to attributes of individuals with the more macro-level effects generated by the nature of structural positions within the market and production.