It is bitter, the bread that has been made by slaves.

Our name is legion though our oppression be great... we war with oppression in every formwith rank, save that which merit gives.

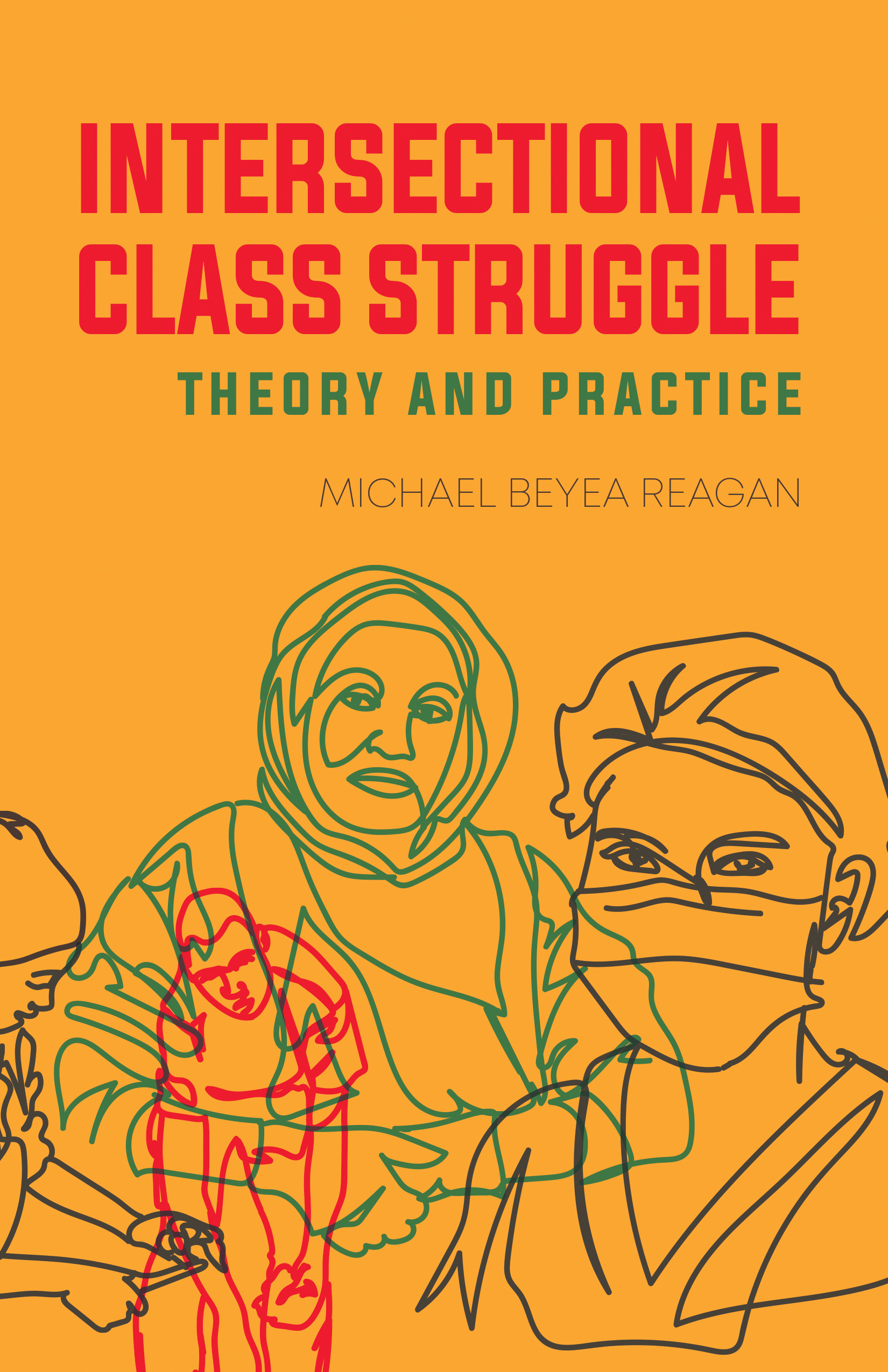

Preface: Of Ourselves, a New Foundation for Class

When I started working on this project in 2016, the election of billionaire Donald Trump had just hit like a freight train. Social movements that had been winning significant victories in the previous yearsuch as Black Lives Matter, the Indigenous movement against Keystone XL, Latinx immigrant struggles, and womens movements against sexual violencewere knocked onto a defensive footing and had to adjust to the new terrain. Most analysts who tried to explain the election results looked alternatively to race, class, or gender, often as exclusive frameworks, for the cause. A major facet of the debate was whether it was the racism of voters supporting Trumps xenophobia, or their class interests, as a backlash to 40 years of neoliberalism, which led to Trumps election. Still others framed it as a manifestation of a deeply misogynistic culture not yet ready to elect a woman, Hillary Clinton, his Democratic Party challenger. As with the investigation of a train wreck, scholars, organizers, and analysts picked through the debris of the election to piece together what had just happened.

Class was certainly one component of the election but, as with most things in life, the ultimate causes were complicated. The questions over what explained the rise of Trump and the renewed interest in the role of class, especially the white working class, is just one example of a class resurgence in our political moment. From the surprise campaigns of Bernie Sanders and Jeremy Corbyn, to laments about the unprecedented wealth inequality of the second gilded age, to debates over the primacy of class or race by contemporary academics and activists, social class is once again a hot topic. Because it has emerged as one of the more important political dynamics of the twenty-first century, we need to take a moment to better understand what it is that we are talking about when we speak of class: What is it? Why is it often connected to conflict and struggle? What is the working class? And why are class analysis and movements of the working class seeing a resurgence right now? To answer these questions, Intersectional Class Struggle argues that social class is defined by the difference and variety of us, regular working people, in our everyday lives. In the last analysis, class is made of ourselves.

Intersectional

Despite the interest, much of the contemporary debate about class is impoverished, and Trumps election is no exception. In the social train wreck that the election revealed, using isolated pieces of wreckage from the crash, the analysis that people drew was only partial. Was it race, or class, or gender that best explained the social crisis? This was simply the wrong question to ask; the obvious answer was yes. Unfortunately, this fractured perspective framed virtually the entirety of the mainstream debate with arguments based on exclusive and essential race or class explanations. To understand each social factor as distinct, rather than a complex whole of the social totality, in which race, class, and gender (along with immigration, disability, colonialism, and other vectors of social power) were mutually reinforcing social phenomena, was part of the problem. But more than this, the language and ideas used to discuss class were particularly poor, alternatively viewing level of education or income and tax register as an analytic stand-in for class. At the core of the problem of discussing class was an inability to define it.

One helpful corrective is the concept of intersectionality. Trump ran specifically on class issues, or, shall we say, a particular articulation of white working-class masculinity was at the foundation of his campaign. He used the language of class to speak directly to wage earners. He fostered racial fear by telling audiences that they (immigrants) are taking our jobs, theyre taking our manufacturing jobs. Theyre taking our money. Theyre killing us. His record of abuse of women fit into a pattern of patriarchal violence and braggadocio. The odiousness of a figure such as Trump is hard to face, but even harder to understand are the motivations of his supporters, who are also often the targets of his violence. Despite the offensive and harmful language he used about women, a majority of white women voted for Trump. And he won their vote despite facing sexual assault allegations and running against the first major-party woman presidential nominee.

Demonstrating the need for intersectional analysis, in the complex phenomenon of the Trump election, a greater percentage of Latinx voters cast their ballot for Trump than for Mitt Romney, whose father was from Mxico. Although Black voters supported Democrats in overwhelming numbers, more stayed away from the polls in 2016 with Clinton as the candidate than any election in a decade. Of those who bothered voting, a greater percentage of Black voters supported Trump than the Republican candidate in 2012. And if we look at non-voters, tens of millions completely stayed away from the polls. Many of these non-voters were both culturally and structurally what we can call working class. This basic divide in the political arena, a class divide, reveals the degree to which class and its intersections with race and gender influenced the election and the political institutions of our time.

However, to look at any one of these factorsgender separate from race separate from classwithout considering them in all in their totality leaves us with a diminished understanding of social power and oppression. If we think about how these factors intersect, how particular sets of interests are articulated in particular historical moments, not only will our understanding be improved but so too our movements for liberation.

Class

In this book, I argue that class can help us understand these apparent contradictions. In much of the work on intersectionality, however, the thinking about class is not robust. This is in part because the tradition of intersectional theory tended to under-theorize class, as I explain more in the introduction. This poor footing has had spillover effects into our movements today and our analysis of contemporary events. In the election debate, depending on how one defined classby education or incomevery different explanations came forward. For those who saw education as a defining factor, Trumps election was the revenge of the white working class, in which those with less education voted in increasing numbers for Trump. Others argued that Trumps support from working-class voters was a myth, that it largely came from middling business owners and that his voters were better off economically compared to most Americans. Trump contributed to this confusion, equating working-class interests to protect jobs with the white supremacist fear of immigrants, and a particular brand of violent and reactive masculinity.

Unfortunately, this equation of working-class interests with whiteness wasnt limited to Trump. In his rejection of reparations and insistence on increasing police funding in the wake of the 2020 Black Lives Matter uprisings, candidate Bernie Sanders also demonstrated a construction of working-class interests with white interests. This is not to equate these two very different politicians; Sanders is a politician on the other side of the political universe from Trump, with a long history of anti-racist activism. I point to Sanderss weaknesses on race to demonstrate that our political understanding of class needs some serious work, even for the best of us on the left. Focusing on programs to establish universal working-class standards from the harm of American capitalism is laudable and would provide great relief for working-class people of color. But color-blind policies cannot adequately address the difference and diversity to be found in the American working class or the historic inequities that affect Black America. If class is made of ourselves, then we need to reflect the variety of working-class experience in our class politics.