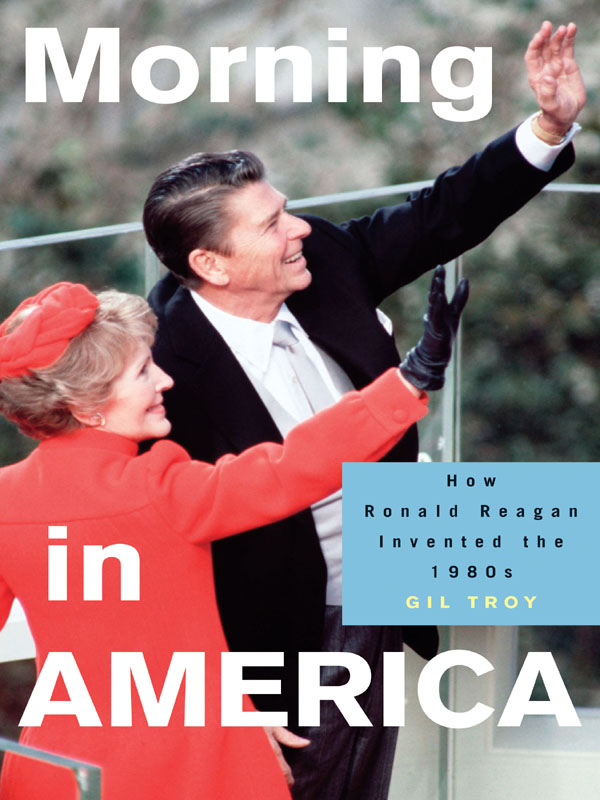

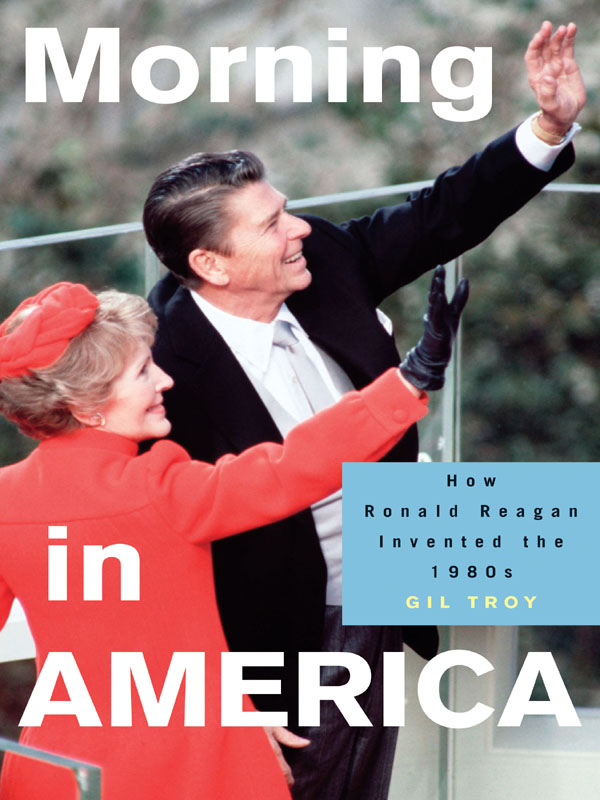

Morning in America

POLITICS AND SOCIETY IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY AMERICA

Series Editors: William Chafe, Gary Gerstle, Linda Gordon, and Julian Zelizer

A list of titles in this series appears at the back of the book.

Morning in America

How Ronald Reagan Invented the 1980s

GIL TROY

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2005 by Gil Troy

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 3 Market Place, Woodstock, Oxfordshire, OX20 1SY

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Troy, Gil.

Morning in America : how Ronald Reagan invented the 1980s / Gil Troy.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index.

ISBN 0-691-09645-7 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. United StatesCivilization1970 2. United StatesSocial conditions1980 3. Nineteen eighties. 4. Reagan, RonaldInfluence. 5. Politics and cultureUnited StatesHistory20th century. 6. United StatesPolitics and government19811989. I. Title.

E169.12.T765 2004

973.927092dc22 2004055295

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Dante

Printed on acid-free paper.

pup.princeton.edu

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

To our four children

Golden doves, harbingers of spring and righteousness, with the hope that you will grow:

To learn knowledge and ethics, to master subtleties.

To embrace the moral discipline of wisdom, justice and right and goodness.

PROVERBS I:23

Contents

1980

Cleveland

1981

1600 Pennsylvania Avenue

1982

Hill Street

1983

Beaufort, South Carolina

1984

Los Angeles

1985

Brooklyn, New York

1986

Wall Street

1987

Mourning in America

1988

Stanford

1989

Kennebunkport, Maine

1990

Boston

Morning in America

Introduction

Ronald Reagans Defining Vision for the 1980sand America

There are no easy answers, but there are simple answers.

We must have the courage to do what we know is morally right.

RONALD REAGAN, THE SPEECH, 1964

Your first point, however, about making them love you, not just believe you, believe meI agree with that.

RONALD REAGAN, OCTOBER 16, 1979

One day in 1924, a thirteen-year-old boy joined his parents and older brother for a leisurely Sunday drive roaming the lush Illinois countryside. Trying on eyeglasses his mother had misplaced in the backseat, he discovered that he had lived life thus far in a haze filled with colored blobs that became distinct when he approached them. Recalling the miracle of corrected vision, he would write: I suddenly saw a glorious, sharply outlined world jump into focus and shouted with delight.

Six decades later, as president of the United States of America, that extremely nearsighted boy had become a contact lenswearing, famously farsighted leader. On June 12, 1987, standing 4,476 miles away from his boyhood hometown of Dixon, Illinois, speaking to the world from the Berlin Walls Brandenburg Gate, Ronald Wilson Reagan embraced the one great and inescapable conclusion that seemed to emerge after forty years of Communist domination of Eastern Europe. Freedom leads to prosperity, Reagan declared in his signature dulcet tones that made fans swoon and critics cringe. Freedom replaces the ancient hatreds among the nations with comity and peace. Freedom is the victor. Offering what sounded then like a pie-in-the-sky challenge or a pie-in-the-sky prayer, President Reagan proclaimed: General Secretary Gorbachev, if you seek peace, if you seek prosperity for the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, if you seek liberalization: Come here to this gate! Mr. Gorbachev, open this gate! Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!

Another seventeen years later, on June 11, 2004, Ronald Reagans funeral climaxed a week of Lincolnesque commemorations. Contradicting its own editorial line, the New York Times front page hailed Reagan for project[ing] the optimism of [Franklin D.] Roosevelt, the faith in small-town America of Dwight D. Eisenhower and the vigor of John F. Kennedy. The 2004 Democratic nominee, Senator John Kerry, gushed: He was our oldest president but he made America young again. The Massachusetts Turnpike, a central artery carrying hundreds of thousands of opponents now often caricatured, eighties-style, as Chardonnay-sipping, NPR-listening, New York Timesreading, Reagan-hating yuppie liberals, flashed an electronic sign saying: GOD SPEED PRESIDENT REAGAN. The respect and affection millions expressed, be it in silence, tears, or wistful reminiscences, constituted Ronald Reagans final gift to the American people. He brought us all together for one last time, wherever we were, Reagans speechwriter extraordinaire Peggy Noonan wrote.

In the 1980s Ronald Reagan offered his fellow Americans a perspective, a set of glasses that helped their glorious sharply outlined world jump into focus. For some, it was a miracle that would see America revive, the Soviet Union falter, and the once seemingly unassailable Berlin Wall fall. For others, Reagans vision represented a national myopia that was immoral, adolescent, and dangerous. But then as now, whether they shouted in delight or muttered in frustration, few could deny Reagans significanceor the importance of the decade he dominated, as his funeral confirmed.

Reagans vision represented his keystone contribution to the 1980s, a decade of boom times and boom-time values. Perhaps the biggest consumer revolt of the period came in 1985, when the Coca-Cola company unveiled New Coke, a sweeter, tangier, more Pepsilike version of Americas national beverage. Reporters played the grassroots backlash as a modern American Revolution, defending baseball, hamburgers, Coke, although some critics simply grumbled that New Coke did not mix well with their rum. When Coca-Cola retreated, Senator David Pryor, an Arkansas Democrat, called old Cokes resurrection a very meaningful moment in the history of America. It shows that some national institutions cannot be changed. This rebellion was a quintessential 1980s story: in the disproportionate reaction to a minor, symbolic problem; in the application of 1960s grassroots tactics to a decadent, consumer culture issue; in the anger of Reagan country mobilized against change; in the sweet strains of nostalgia and patriotism mingling with self-indulgence; in the gap between the simple media story line and the messier realities.

The centrality of a soft drink to the identity of both New Coke and Classic Coke advocates reflected Americas epidemic consumerism. New technologies, ideologies, and bureaucracies, along with revolutions in economics, marketing, advertising, and conceptions of leisure, had transformed the cautious American customer, once wary of chain stores, into the 1980s sale-searching, trend-spotting, franchise-hopping shopper. Spurred by Reagans gospel of progress and prosperity, Americans happily indulged themselves. God wants you to succeed, Reverend Robert Schuller preached from his shopping center for God, the $19.5 million Crystal Cathedral seating three thousand.

Shopping became the great American religion, with advertising jingles uniting Americans through a common liturgy. Loudmouths in stadiums would shout Tastes great, echoing a popular Budweiser commercial for light, spelled lite, beer. The Pavlovian crowd would respond: Less filling!round after round after round. Malls sprouted like mushrooms across the landscape, creating huge, homogenized, artificial environments, killing off main streets and helping franchises gobble up individual entrepreneurs. And Americans became more obsessed than ever with having the latest, the hottest, the bestan obsession exemplified by the craze for cherubic-faced Cabbage Patch dolls, the must-get gift of Christmas 1983 that arrived with a birth certificate and hospital papers.

Next page