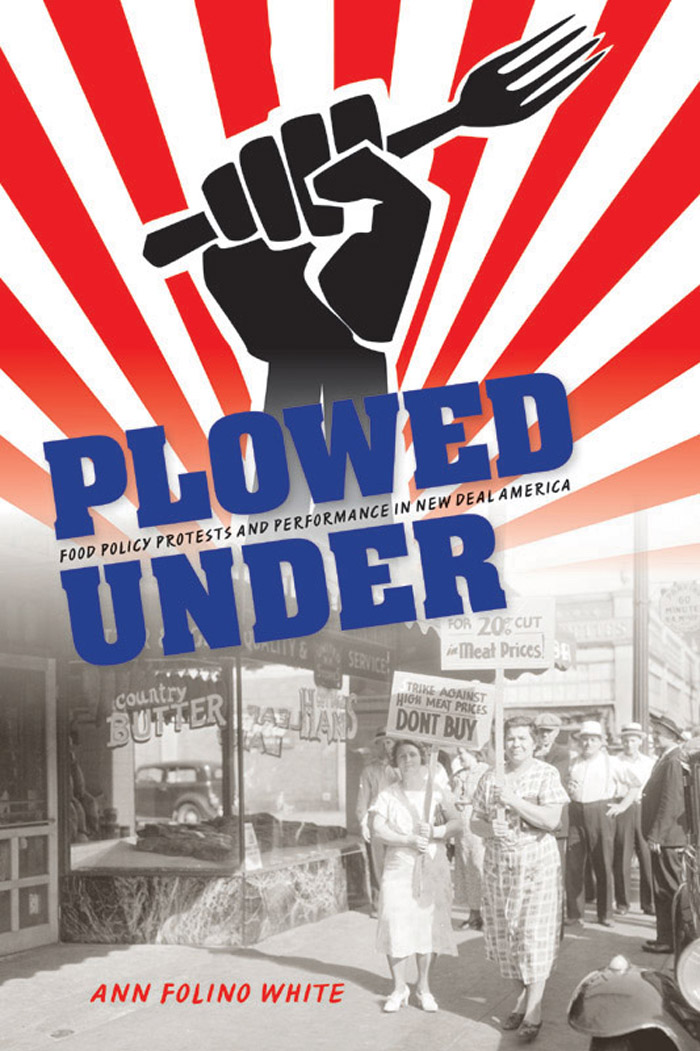

PLOWED UNDER

PLOWED UNDER

FOOD POLICY PROTESTS AND PERFORMANCE

IN NEW DEAL AMERICA

ANN FOLINO WHITE

INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS Bloomington & Indianapolis

This book is a publication of

INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS OFFICE

of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

Telephone 800-842-6796

Fax 812-855-7931

2015 by Ann Folino White

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

Manufactured in the

United States of America

Library of Congress

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

White, Ann Folino.

Plowed under : food policy protests and performance in new deal America / Ann Folino White.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-253-01540-2 (pb : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-253-01537-2 (cl : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-253-01538-9 (eb) 1. Agri culture and stateUnited States History20th century. 2. Protest movementsUnited StatesHistory 20th century. 3. New Deal, 19331939. I. Title.

HD1761.W427 2014

338.197309043dc23

2014022234

1 2 3 4 5 20 19 18 17 16 15

For Marc and June

Contents

Acknowledgments

I received generous financial support from Michigan State University for the completion of this book, including a research leave sponsored by the Residential College in the Arts and Humanities, an Interdisciplinary Research Incubator Grant from the College of Arts and Letters, and a Humanities and Arts Research Program subvention from the Office of the Vice President for Research and Graduate Studies. Funding from the College of Arts and LettersUndergraduate Research Initiative supported Magdalena Kopaczs translations for this book; Ms. Kopacz also gave freely to me important insights into her hometown of Hamtramck, Michigan, for which I am very appreciative. The College of Arts and Letters, the Residential College in the Arts and Humanities, and the Honors College supported David Clauson as my research assistant throughout the four years of his undergraduate education; Davids remarkable intellect and tireless assistance made this book better.

I am also thankful to the American Theatre and Drama Society for the Publishing Subvention Award and to the American Society for Theater Research, the Alice Berline Kaplan Center for the Humanities, and the graduate school at Northwestern University for grants that supported my research. Thanks to Jarod Roll and Don Binkowski for sharing research and to Hannah Tesman and Matthew Campbell and Whitney Minter for opening their homes to me during research trips. Thanks also to Indiana University Presss reviewers for their deep engagement with my work and to the editorial and production staff for their thoroughness and responsiveness throughout this process.

Many thanks to the faculty of the Interdisciplinary PhD in Theatre and Drama Program at Northwestern University, particularly Robert Launay, Nancy MacLean, Susan Manning, and Sandra L. Richards. My graduate cohorts were the first readers of this project and remain my most trusted colleagues. Thank you, Amber Day, Christina McMahon, Jesse Njus, Scott Proudfit, and Daniel Smith. While I am also indebted to Shelly Scott and Stefka Mihaylova for reviewing many drafts, I am most grateful to them for their good counsel and friendship.

Several friends and colleaguesCaroline Kiley, Michael Largey, Melvin Pena, Sam OConnell, and Patti Rogersoffered valuable advice and critiques of this project at various stages. My colleagues Rob Roznowski and Chris Scales have served as important sounding boards and mentors. I am also incredibly grateful to Joanna Bosse for the open invitation to share ideas and for playing hooky with me. Many thanks to all.

To Tracy C. Davis, whose generous spirit, intellectual acuity, and practical advice have enriched my research, my teaching, and my life: thank you for telling me to wear a sweater in the archives.

The Folino and White families have sustained me, and so this project, in all the most important ways. They have taken great care to encourage me and to nurture and entertain my daughter June whenever this project required me to be away from her. To my mother and father, Anita and Dino Folino, thank you for teaching me the importance of perseverance and a well-timed joke. You have been my most important teachers and are the reason I became one. To my June, who requires the tooth fairy to sign for pick up, thank you for your impatience with and interest in me. My husband Marc ensured that I had everything I needed to complete this book. He is the kindest person I know and my truest friend. I am grateful that we share our lives.

Introduction

In all my experience in political life I never heard of anything so truly absurd as helping the people by killing pigs and destroying crops, by paying the farmer not to toil, paying the farmer not to work his land. There is no virtue in waste. There is virtue in relieving the poor and helping them, but there is no possible place where you can find virtue in waste.

Clarence Darrow, September 1933

Famed attorney and leader of the American civil Liberties Union Clarence Darrow, like so many others, thought the 1933 Agricultural Adjustment Act ( AAA ) to be immoral: How could the government pay farmers to leave fields fallow while children rummaged in trash for food and thousands of Americans stood in breadlines day after day? How could President Franklin D. Roosevelt actively throw away food in the face of so much want? Darrow surely knew the currency of his rhetoric and likely believed in it as well. The cultural code of conduct regarding food and the nobility of farming were so deeply engrained in the American consciousness that the AAA seemed to flout basic American morality when hungers call to obligation was most insistent, when access to food was truly at stake for millions of Americans. Secretary of Agriculture Henry Wallace anticipated that this New Deal agricultural program would face an unfavorable public reaction,ways that exceeded the realm of rhetoric. They engaged in what might be called a theater of food in their protests to challenge the AAA s morality. The federal government also turned to foods potency in performance to convince the public of the AAA s benefits.

This book tells the story of the moral issues raised by the Agricultural Adjustment Act from the distinct perspectives of farmers, consumers, agricultural laborers, the federal government, and theater artists. It analyzes five case studies that map out the emergent controversies surrounding the AAA from its passage in the spring of 1933 (and its subsequent versions in 1936 and 1938) to the general adoption of its policies by 1939. Plowed Under begins by examining the U.S. Department of Agricultures ( USDA ) promotion of the humanitarian aspects of the AAA through public exhibits at the 193334 Worlds Fair in Chicago. The next three chapters examine challenges to the official narrative, through protests by three groups of citizens, whose experiences with and complaints against the act were defined by their economic relationships to agriculture and the cultural significance of particular foods. They include the Wisconsin Cooperative Milk Pool strike staged by property-owning, white dairymen in 1933; the Womens Committee for Action against the High Cost of Living meat boycott in Hamtramck, Michigan, staged by female, working-class, Polish American consumers in 1935; and the Missouri sharecroppers demonstration staged by black and white landless/ homeless laborer families in 1939.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.