This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

601 North Morton Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47404-3797 USA

www.iupress.indiana.edu

Telephone orders 800-842-6796

Fax orders 812-855-7931

Orders by e-mail

First paperback edition 2010

2000 by Indiana University Press

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or

by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying

and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval

system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

The Association of American University Presses Resolution

on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of

the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence

of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

Manufactured in the United States of America

The Library of Congress cataloged the original edition as follows:

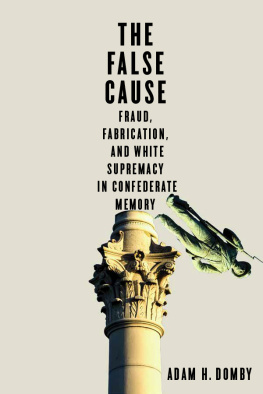

The myth of the lost cause and Civil War history /

Gary W. Gallagher and Alan T. Nolan, editors.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-253-33822-0 (cl : alk. paper)

1. Confederate State of AmericaHistoriography. 2. United StatesHistoryCivil

War, 18611865Historiography. 3. Confederate States of AmericaHistory. 4. United

StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865. I. Gallagher, Gary W. II. Nolan, Alan T.

E487 .M97 2000

973.713072dc21 00-036978

ISBN 978-0-253-22266-4 (pbk.)

2 3 4 5 6 15 14 13 12 11 10

Introduction

Gary W. Gallagher

White Southerners emerged from the Civil War thoroughly beaten but largely unrepentant. Four years of brutal struggle had ravaged their military-age male population, vastly altered their physical landscape and economic infrastructure, and destroyed their slave-based social system. They grimly acknowledged the superior might of United States military forces and understood the futility of further armed resistance. Yet the majority of ex-Confederates, who had remained hopeful of establishing a new slaveholding republic until late in the conflict, did not believe they had fought for an unworthy cause. During the decades following the surrender at Appomattox, they nurtured a public memory of the Confederacy that placed their wartime sacrifice and shattering defeat in the best possible light. This interpretation addressed the nature of antebellum Southern society and the institution of slavery, the constitutionality of secession, the causes of the Civil War, the characteristics of their wartime society, and the reasons for their defeat. Widely known then and now as the Lost Cause explanation of the Confederate experience, it drew strength from the pages of participants memoirs, from speeches at veterans reunions, from ceremonies at the graves of soldiers killed while serving in Southern armies and other commemorative events, and from artwork with Confederate themes.

The architects of the Lost Cause acted from various motives. They collectively sought to justify their own actions and allow themselves and other former Confederates to find something positive in all-encompassing failure. They also wanted to provide their children and future generations of white Southerners with a correct narrative of the war.

Many Northerners who watched the developing Lost Cause school of interpretation worried that it might gain wide acceptance. For example, Frederick Douglass labored throughout the postwar decades to combat what he perceived as Northern complicity in spreading Lost Cause arguments. Aware that most former Confederates had not forsworn their belief in the rightness of their experiment in nation building, he complained in 1871 that the spirit of secession is stronger today than ever. Douglass described that spirit as a deeply rooted, devoutly cherished sentiment, inseparably identified with the lost cause, which the half measures of the Government towards the traitors has helped to cultivate and strengthen. Nearly a quarter-century later, a publication sponsored by the Grand Army of the Republic in Massachusetts mounted an attack on what one of its subheadlines termed the Lost Cause of Historical Truth. Concerned that school textbooks had fallen under the sway of those who sought to mask the true causes and meaning of the Civil War, this article staked its position clearly in referring to the conflict as the Great Pro-Slavery Rebellion. In 1925, a Pittsburgh newspaper cheered news that a shortage of funds had stopped work on a massive Confederate memorial at Stone Mountain, Georgia: Just enough work has been done to remind the traveler that there is the lost cause, conceived in hatred, and interrupted in its course for want of support. Nothing could constitute a more appropriate insignia to a

The sculptures at Stone Mountain eventually were completed, and Lost Cause symbols and interpretations remained visible and sometimes hotly debated throughout the twentieth century. Controversies erupted in the 1990s over the public display of Confederate flags in South Carolina and Georgia, the inclusion of Robert E. Lees picture on a flood wall along the James River in Richmond, and the presence of early-twentieth-century statues of Confederate heroes on the campus of the University of Texas. Public discussion of such questions suggests the degree to which the Lost Cause remains part of the modern Civil War landscape.

The Lost Cause also has attracted significant attention from historians interested in its nineteenth-century manifestations as well as its long-term impact on American understanding of the Civil War. In a pioneering effort, Rollin G. Osterweis depicted the Lost Cause as an extension of antebellum Southern romanticism and found it much in evidence during the mid and late twentieth century. Gaines M. Fosters landmark study, in contrast, argued that the Confederate tradition played an increasingly marginal role in the South after the turn of the century. Charles Reagan Wilson explored connections between the Lost Cause and postwar Southern religion, while Thomas L. Connelly and Alan T. Nolan focused on Robert E. Lee as a pivotal figure whose Lost Cause image gained national favor. The Southern Historical Societys Papers and the Confederate Veteran, major outlets for Lost Cause authors during a span of several decades, received recent attention from Richard D. Starnes and John A. Simpson respectively. On the artistic side, Mark E. Neely Jr., Harold Holzer, and Gabor S. Boritt analyzed popular nineteenth-century prints and lithographs that formed a Confederate iconography, and Kirk Savages study of nineteenth-century monuments allotted considerable attention to the heroic statue of Lee on Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia. Jim Cullens investigation of

The essays that follow seek to build on previous literature by engaging various aspects of the white Souths response to defeat, efforts to create a suitable memory of the war, and uses of the Confederate past. Readers should be aware that the collection does not pretend to compete with the monographic literature on the Lost Cause. Nor does it present a unified interpretation of the many dimensions of the subject. Instead, the essays focus on both specific and general topics, revisit some longstanding debates and well-known actors, illuminate continuities between antebellum and postwar attitudes, and underscore how political and ideological antagonisms divided white Southerners who generally accepted basic elements of the Lost Cause interpretation of slavery, secession, and the war. Several of the essays discuss the degree to which Lost Cause arguments continue to influence modern writers and, by extension, the large lay audience interested in the Civil War.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of