Green Capital

Green Capital

A New Perspective on Growth

Christian de Perthuis and Pierre-Andr Jouvet

Translated by Michael Westlake

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

NEW YORK

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

Copyright 2013 Odile Jacob

Translation copyright 2015 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54036-0

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Perthuis, Christian de.

[Capital vert. English]

Green capital : a new perspective on growth / Christian de Perthuis,

Pierre-Andr Jouvet; translated by Michael Westlake.

pages cm

Translation of: Le capital vert : une nouvelle perspective

de croissance, published in 2013.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-17140-3 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-231-54036-0 (e-book)

1. Environmental economics. 2. Sustainable development.

I. Jouvet, Pierre-Andr. II. Title.

HC79.E5P45713 2015

333.7dc23

2015002297

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: Noah Arlow

References to Internet Web sites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing.

Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

Contents

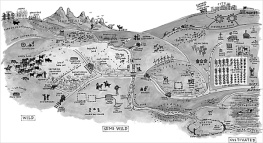

FOUR THOUSAND YEARS AGO, the fate of the Sumerians revealed that when growth is driven by capital accumulation that preys on the environment, it will eventually self-destruct. Thanks to their control of irrigation, the inhabitants of Sumer developed agriculture, writing, law, and the city; but because they were unable to master drainage, the indispensable complement to irrigation in arid areas, their civilization vanished as a result of the sterilization of the soil by salt. The inhabitants of Easter Island, who had also developed one of the first writing systems, experienced a similar fate.

Scientific reports all reveal the rapid loss of this biodiversity. Suppose that the services currently provided for free by biodiversity were reduced by a quarter between now and 2050; this would amount to a 10 percent decrease in global GDP, probably irreversibly.

Despite the supportive discourse of international organizations like the OECD and the World Bank, which has lent credibility to the idea of green growth, these new environmental concerns remain on the periphery of political and economic decision making. Worse, following the deep recession of 20082009, the outlook of decision makers has shortened: what counts now is a rapid return to growth and the reduction of unemployment. As for the color of growth, they seem to say, well think about that later! Barack Obamas first presidential campaign in the fall of 2008 focused on two societal projects: the extension of health coverage and controlling greenhouse gas emissions. His 2012 campaign revolved around one point only: who, given the choice between the incumbent president and his Republican opponent, would be most able to stimulate the economy and create jobs? A few months earlier, the environment had likewise disappeared from the debate around the French presidential campaign. International life is in step with this restricting of the field of vision. In 2009, when the Copenhagen summit brought together many heads of state, climate change still seemed to be a major challenge for policy makers. The economic and financial crisis has since taken its toll. By 2013, the marathon sessions that counted were those that sought to save the euro or to defend the quality of ones sovereign debtin short, to repair the economic machine and quickly restore growth. Climate change, ecology, the color of growth: these are no longer on the agenda.

In adopting such an approach, the industrialized world is indefinitely postponing any ambitious action to address climate change and the challenges presented by the environment more generally. With varying degrees of awareness, we are passing on the perils of global warming and loss of biodiversity to future generations. But by buttressing ourselves with such narrow visions of a return to growth, we are at the same time depriving ourselves of the most appropriate way of emerging from the current economic depression. Everyone vaguely feels that emergence from the crisis will not happen by copying past formulas. This time, exit requires a new wave of investment and innovation that will reconfigure the economic structure, as has taken place historically with the advent of animal traction, the steam engine, electricity, the computer, and the Internet. It is our personal conviction that green capital will play a central role in the reconstruction of the economy. But for this to happen, it is essential to stop pushing it to the periphery, and instead to place it at the heart of economic debates. The aim of this book is to contribute to this process by providing the reader with an itinerary consisting of five main stages.

its center of gravity has simply shifted to China and newly emerging countries. Nor has growth been held back by any shortage of raw materials. Yet at the same time the impact of humanity on the natural environment has increased, threatening the major regulatory functions of natural capital such as climate stability and biodiversity. But these regulatory functions are incorporated into neither prices that calibrate values nor aggregates, such as GDP, that measure wealth.

show how it is possible to move from a quantitative notion of the limits to growth based on the scarcity of natural resources to a panoptic outlook concerned with the preservation of the regulatory systems of natural capital. Rather than a representation deeply rooted in an economic concept of natural capital as a stock of scarce resources, there is a shift to a systemic view of natural capital, understood as a complex system of regulatory functions. Because nature is not a commodity that can be traded in a market, it is not possible to assign it a value, as is done for other components of capital. On the other hand, the deterioration of natural systems of regulation has a cost that reflects the use made of natural capital. We therefore include the cost of pollution in the production function because it contributes in the short term to the supply potential of the economy, although simultaneously weakening its long-term growth path. In the short term, pricing pollution changes the preexisting combination of production factors by attributing to the use of natural capital part of the supply previously attributed to labor and capital. By pricing pollution, green capital thus affects the short-term equilibrium and becomes a factor of production in which it is necessary to invest for long-term expansion. There are many ways of doing this. Adding a factor to the production function gives rise to an apportioning problem: Should it be capital or labor, the blue-collar worker or the boss, high-income countries or low-income countries who are obliged to cut back their revenue to pay for this new component of the natural capital that is progressively destroyed if a value, and hence a price, is not attached to it? This approach is consistent with the theoretical extensions that have progressively enriched the standard growth model developed in the 1950s by Robert Solow.

the groundbreaking experiments that are opening up new fields for investment and thus growth.

look in greater depth at the energy aspects of the transition to a green economy. First, various energy transition models are discussed: the U.S. energy revolution driven by the large-scale exploitation of oil and gas shale is a very different option than the low-carbon strategy adopted by Europe or the long-term diversification aimed at by oil-producing countries and the major emerging economies. The catalyzing role of energy pricing, and its climatic and environmental impacts, is then examined, along with the specific issue of nuclear power: though a non-CO2-emitting primary energy source, it nonetheless gives rise to many other questions, as is shown by the French example. There follows an analysis of the various innovations that will accompany the energy transition: innovations in technology, of course, but also innovations in social organization, land management, and the way people live, along with innovations in terms of governance and the conduct of public affairs, without which public debates run the risk of being all talknot having any real impact on policy decisions.