Copyright 2009 by Wayne Biddle

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Manufacturing by The Courier Companies, Inc.

Book design by Chris Welch

Production manager: Andrew Marasia

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

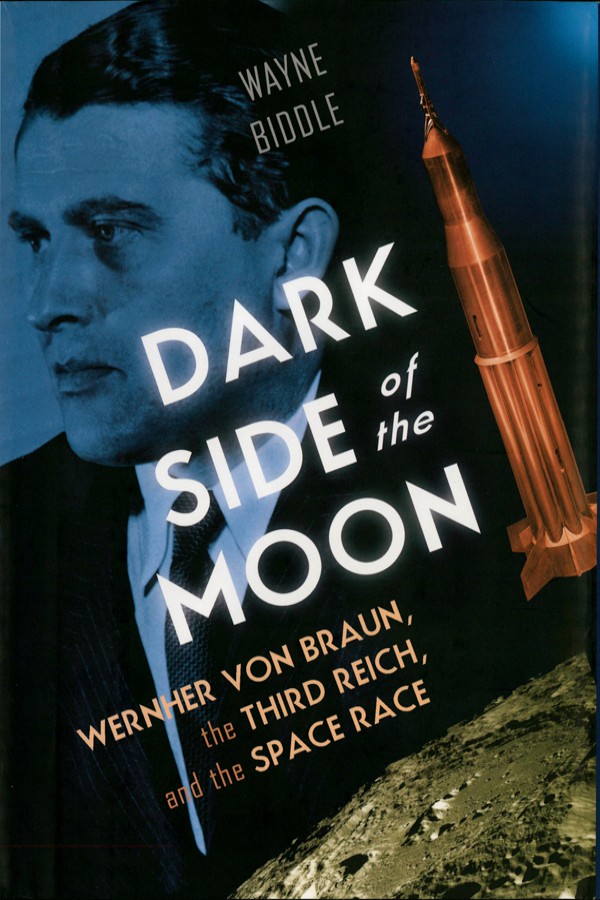

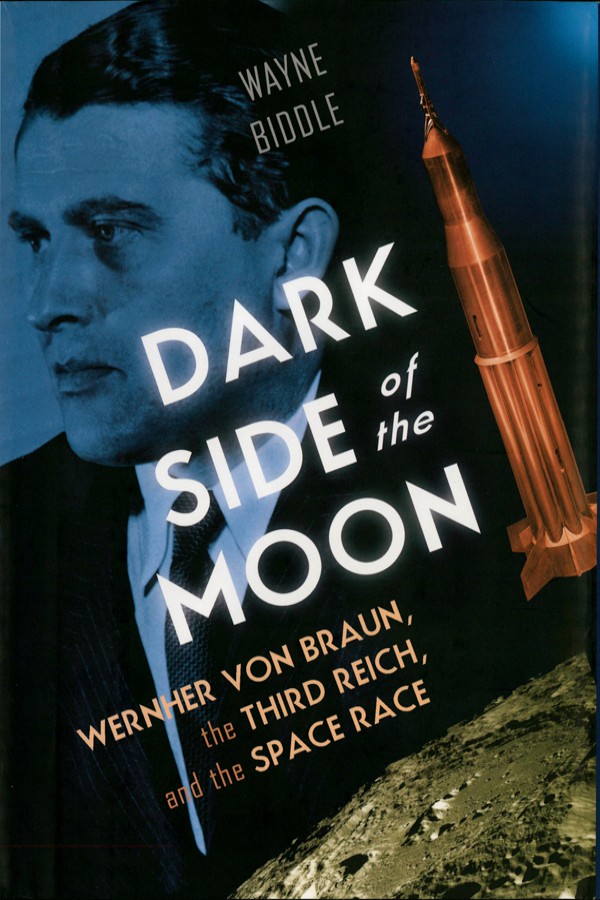

Biddle, Wayne.

Dark side of the moon : Wernher von Braun, the Third Reich, and the

space race / Wayne Biddle.1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-393-05910-6 (hardcover)

1. Von Braun, Wernher, 1912-1977. 2. RocketryGermanyBiography.

3. RocketryUnited StatesBiography. 4. World War, 1939-1945Science.

5. Space raceUnited StatesHistory20th century.

6. GermanyPolitics and government1933-1945. 7. Cold War. I. Title.

TL781.85.V6B53 2009

629.4092dc22

[B]

2009015572

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

1234567890

FOR JEAN

INTRODUCTION

The saying that no one is voluntarily wicked nor involuntarily happy seems to be partly false and partly true; for no one is involuntarily happy, but wickedness is voluntary.

Nicomachean Ethics

T HE SUBJECT OF moral responsibility has a long history, stretching at least as far back as the fourth century BC. In Book Three of his Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle discussed how to decide whether someone should be praised or blamedeither way, that isfor an action. Simply put, a person is morally responsible for something if he was causally responsible for it, if he was in a position to know that it would come about, if what he did was freely undertaken, and if he was fully rational. As courts of law demonstrate every day, real life is infinitely complicated and each segment of this statement has been masticated by philosophers ever since, but it is fair to say that there is broad agreement in Western culture that if all four conditions are met, then an individual is on the spot for better or worse.

The issue of whether scientists are responsible for the outcomes of their work has been especially turbid since they became powerful enough during the last century to alter the landscape. In 1962, the chemist and sociologist Michael Polanyi (1891-1976) argued in an influential essay called The Republic of Science that the practical results of pure science are often unforeseen; therefore a scientist may not be liable for what others do with them. He recalled that in April 1945, he and Bertrand Russell were asked on a British radio show what applications might arise from Einsteins E = mc2, and they both drew a blank.

Laws of nature are morally neutral, everyone agrees. But so-called pure sciencethe discovery or extension of fundamental theoryis practiced by only a small fraction of the profession. The rest take accepted principles and apply them to carefully defined problems with definite notions about the solutions, which may or may not have practical outcomes. Most engineers, of course, are directly involved with applications in the everyday world. Nonetheless, the separation between scientists and engineers is often impossible to delineate. Yet the convention that scientists as a group exist in a stratum detached from and untainted by common sociopolitical forces, and are thus somehow above reproach, has proved remarkably durable, albeit weakened by the past half-century of disasters clearly traceable to their activity.

Do you think scientists should be blamed for wars? Einstein? He looked for fundamental truths and his formula was used for an atomic bomb. Alexander Graham Bell? Military orders that kill thousands are transmitted over his telephone. Why not blame the bus driver who takes war workers to their factories? How about movie actors who sing for the U.S.O.? These comments may sound philistine today, but they were made six years after the end of World War II in a respectful article in The New Yorker magazine by a man then well on his way to becoming one of the eras most famous and revered technologists. The German rocket scientist Wernher von Braun, who had played a principal role in creating the V-2 wonder weapon for the Third Reich, had come to America under U.S. Army auspices to continue his work. What he had really been doing all along was developing the means to travel into outer space, he claimed time and again. Most of his audience never doubted it.

Later generations largely forgot about him, as the imperatives of the Space Age grew quaint. But it is reasonable to posit that no other public figure of the twentieth century was forgiven so much as Wernher von Braun, so that he be allowed to pursue his dream. The army gave him a fresh identity by classifying for decades the most malevolent details of his pre-1945 life. He needed little else besides more of the incredible good luck that had propelled him out of Hitlers Germany into General Eisenhowers America.

There has been much biographical writing about von Braun over the years. Because of government secrecy and popular disinclination, most of it was uncritical until long after he died (of cancer) in 1977. As the archives opened up and cold war restrictions on traveling in eastern Germany relaxed, a few journalists and historians performed the investigative toil of straightening out a record that had been warped by public relations men and pervasive sycophancy.

My own entry into this fray came about because I was one of innumerable members of the postwar baby boom generation who enjoyed von Braun as an inspirational narrator on Walt Disneys television shows about space travel during the mid-1950s. Young boys, especially, built models and read science fiction and believed that mankind would explore the solar system in our lifetime. It is ironic that von Braun had a similar boyhood in the 1920s and managed to transfer it directly into our brains. Also like many of my age, the political atmosphere ten years later led me to wonder skeptically how a Nazi weapons builder could become an American hero. Yes, he played a central role in sending astronauts to the moon, but, by contrast, LBJ would never be forgiven for Vietnam, so why was this man let off the hook? Or so the thinking went.

The question was not merely an artifact of a credulous childhood, but a window into a core phenomenon of American technology and culture. Von Braun moved so seamlessly from Peenemnde, Pomerania, to Huntsville, Alabama, because millions of people wanted him to, because the secrecy and some of the obsessions of the Third Reich were not entirely different from those of postwar America. They wanted to believe in his prophecies, his genius, and his goodness, no matter what. This is why his life remained of interest to me, not because of the exciting hardware he produced, which like all hardware is ultimately trivial when divorced from its social and political context.

My goal for this book was to bring von Braun truthfully through the first thirty-three years of his life in Germany to America in 1945 and then tell how he blended into the late-1940s and 1950s. That was when the torquing of his persona took place, which I believe to be one of the central conundrums of that weird time of anti-Communist hysteria and progress worship. After

Next page