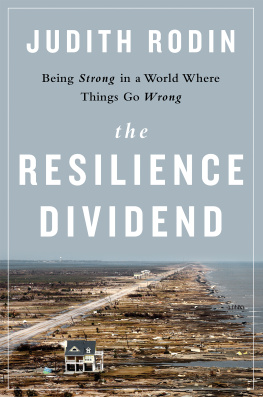

PRAISE FOR THE RESILIENCE DIVIDEND

Dr. Rodins extraordinary leadership has helped introduce the world to the concept of resiliencethe critical strategy for breaking the endless cycle of emergency response and relief for millions of people. From supporting our nations recovery in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy to helping megacities in Asia protect their most vulnerable citizens, Dr. Rodin has made resilience a global priority at home and abroad. Rigorously analytical and powerfully argued, Dr. Rodins book challenges us to work smarter and more collaboratively to predict disasters before they strike and enable citizens to build stronger communities and thriving economies.

Dr. Rajiv Shah, administrator of USAID

With heartbreaking stories and practical examples, Judith Rodin makes a timely and much needed contribution for creating a better world in an increasingly volatile environment. Turning volatility into advantage is a skill that leaders at all levels of any organization can use in building resilience into business models.

Paul Polman, CEO of Unilever

This book makes a compelling case, drawing on stories from countries and communities across the world, that resilience is not just a defense mechanism but a positive gain or dividend, with added value in economic and social terms. The message is timely, given the increasingly disruptive force of climate change and the need to encourage communities to respond positively. It is also a highly readable account because it relies on actual human experience.

Mary Robinson, president of the Mary Robinson Foundation-Climate Justice, and UN Special Envoy on Climate Change

Judith Rodin is a world-class entrepreneurial philanthropist. When she turns her gaze to new areas of engagement, it is both creative and (in a positive sense) destructive. Her insights into resilience shift the boundaries of classic philanthropic, governmental, and business models. For Judith, resilience is not just about defense against natural and manmade threats. She uses resilience as a basis for transforming the human environment. In The Resilience Dividend , she brings her lifes work to bear on the subject, drawing on her deep and personal experiences from around the world. She uses every tool available (including the worlds most advanced technologies) to understand the urban terrain and to deploy real-world solutions. All with the goal of saving and improving human lives.

Dr. Alex Karp, cofounder and CEO, Palantir

Copyright 2014 by The Rockefeller Foundation.

Published in the United States by PublicAffairs, a Member of the Perseus Books Group

All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America. Royalties from the sale of this book will go to The Rockefeller Foundation.

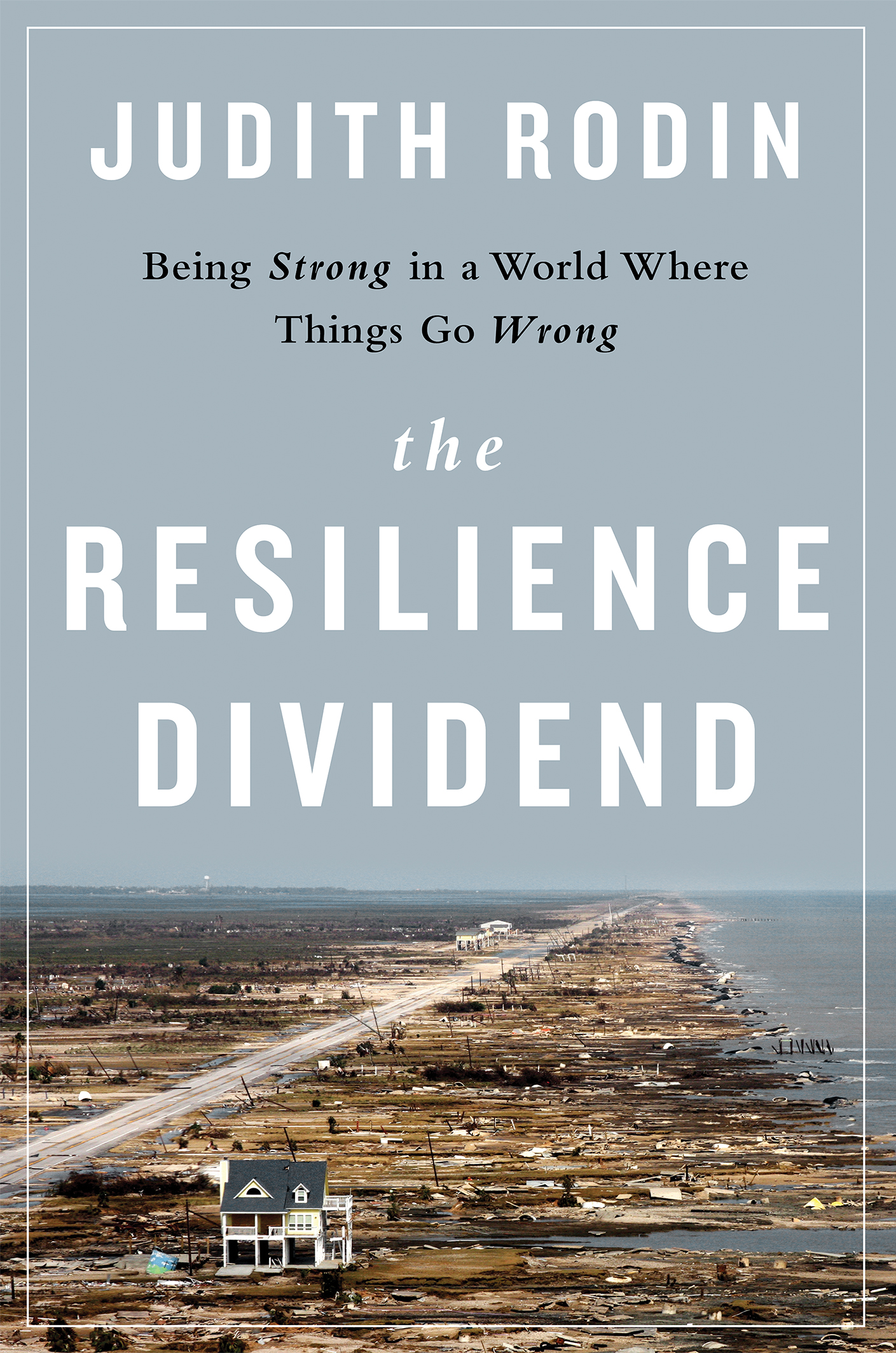

About the cover: Pam and Warren Adams built their home in Gilchrist, Texas, on high columns, knowing they were vulnerable to sea surge from storms along the Gulf Coast. When Hurricane Ike struck in 2008, although their home suffered some damage, it became known as the last house standing in their area.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address PublicAffairs, 250 West 57th Street, 15th Floor, New York, NY 10107.

PublicAffairs books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail .

Book Design by Cynthia Young

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

Library of Congress Catalog Control Number: 2014949467

ISBN 978-1-61039-471-0 (EB)

First Edition

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Paul and Alex

I was in Beijing speaking at a conference on global health when Superstorm Sandy struck New York City with incredible force on October 29, 2012. When I understood just how catastrophic the storm was, I frantically tried to reach my chief of staff, who lives in Brooklyn, but the phone lines were completely jammed. I was worried. Our headquarters are in Manhattan. Many of my colleagues and staff members live in the New York area. I had no idea whether they were OK or what the status of our work was. As I watched the flood waters surging through Wall Street on TV, I urgently kept texting my executive assistant, who lives in New Jersey. No response. As I learned later, communication channels throughout the region had either been taken down or were overwhelmed. Not even emergency personnel could get through. People and places I cared about were in danger, and there was nothing I could do.

In the end, we were lucky. None of our staff members suffered injury, although several had to abandon their flooded homes, and many could not return to them for months. I managed to get a flight back, but only days later. Our New York offices were closed for a week because the area of Manhattan where we are located was without power, but we were able to keep some operations going and to help one another by communicating via our personal e-mail addresses. We were disrupted, for sure, but we continued to function, and the foundation was back to almost normal within a week.

That was not the case for many throughout the region. Superstorm Sandy brought damage beyond what we had ever seen in this area and even greater than we had imagined, though I was well aware of the devastation that a storm of this magnitude could wreak on New York City. Indeed, The Rockefeller Foundation had helped to support the development of a report by the New York City Panel on Climate Change that explored the potential effects of intense hurricanes, extreme wind, coastal flooding, and storm surge on the citys infrastructure. We had also funded groups of architects, engineers, and planners to collaborate on innovative design solutions for the citys response to rising sea levels, which were exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art.

In other words, our region knew a great deal about the worst-case scenarios related to storms and sea rise, but until Superstorm Sandy hit, it had all been hypothetical. Now the nightmare had been realized, and we could see that New York should have been better prepared and could have responded more effectively than it did. It was a wake-up call we could not ignore.

Only weeks after the storm, Andrew Cuomo, governor of New York, convened the NYS2100 Commission, a group of skilled and knowledgeable people whose task was to study the effects of the storm and make recommendations for what we should do to better prepare and rebound more quickly when the next shock hit. The commission had a broad and sweeping charge to make New York more resilient. Governor Cuomo asked me to act as cochair of the commission, and I jumped at the opportunity because I knew The Rockefeller Foundation had a lot to offer. For years, we had been working on issues of resilience, many of them related to climate change and weather disruptions, through projects around the world.

I knew the work of the commission was vitally important, but when I visited some of the areas most devastated by Sandy I realized how truly essential it was. I saw homes destroyed, neighborhoods disrupted, peoples lives in disarray. In Breezy Point, where more than a hundred houses had burned to the ground, we talked with a firefighter who was digging through the rubble of what had been his home. He was trying to find his fathers World War II medals.