I am, as ever, indebted to my wife Pat and to my children for putting up with my interminable ramblings about this little book and every other book that I have written and to my editor at The History Press, Jo de Vries, for her advice and patience.

I am particularly grateful to the team at Dekko , the newsletter of the Burma Star Association, who kindly printed an appeal for help which brought me into touch with Mrs Rhona Palmer and Mrs Angela Benions. Mrs Palmer provided me with a copy of her fathers memoir of the war in Burma and has generously allowed me to include several photographs from his collection. Mrs Benions very kindly lent me a copy of her fathers recollections of the Burma theatre when I failed to find one myself.

I would also like to draw attention to the work of the Kohima Educational Trust. When the veterans of the battle held their last reunion in 2004, they decided to set up a trust to provide assistance with the education of Naga children in memory of the Commonwealth troops who fell in battle, and as an expression of gratitude for the sacrifice and loyalty of the Naga people in whose land the battle was fought. The trust does remarkable and valuable work, and is a cause worthy of support; it can be contacted at www.kohimaeducationaltrust.net.

This book is dedicated to three gentlemen gunners who served their country in the Second World War: my father, Peter Brown, who had the good fortune to arrive at the Burmese border at the best possible juncture of the campaign; to my late father-in-law, Robert Smith, who served in North Africa and Italy; and to John Laindon Cornwell, who was murdered by the Japanese Army on Ballali Island in 1943.

General Satos 31st Division had not only failed to achieve the objectives of the operation, it had been all but destroyed as a viable fighting force. While they were meeting disaster at Kohima, the rest of the great U-Go offensive was unravelling with similar consequences for the rest of the Burma Area Army. At the beginning of the campaign, Gen. Scoones IV Corps had been poised for an offensive of its own, and was not, therefore, ideally deployed for defence. Fearing that the forward elements could become isolated and be defeated in detail, Gen. Slim authorised Gen. Scoones to withdraw to the Imphal plain, thus shortening the Allied lines of communication while the Japanese logistic effort came under increasing strain because of the distances involved, the harsh country and because of interdiction missions flown by the RAF and RIAF.

Concentrating his forces at Imphal allowed Slim and Scoones the opportunity to fight a major battle on their own terms. Commonwealth troops had found that they increasingly had the edge on the Japanese in battle in the jungle and now that they were fighting on the plain, their air combat support, their artillery and their armour were all much more effective than in previous encounters.

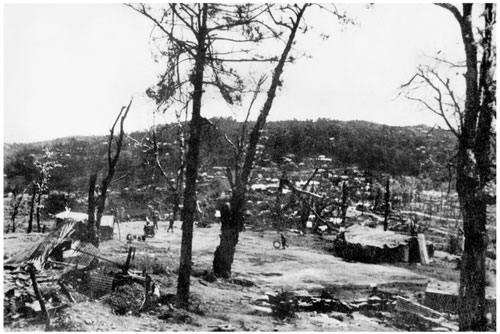

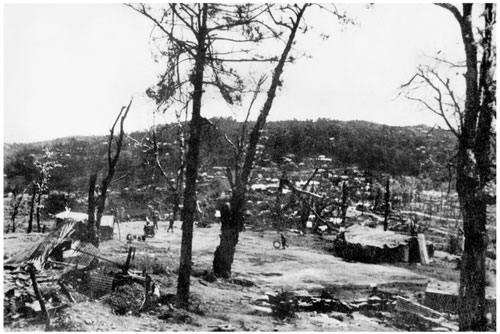

37 A view of the shell-scarred Kohima battlefield. (AB/AWH)

Once the battle was flowing in the Allies favour, and the enemy were in retreat, there was no place where Japanese forces could make a properly coordinated stand which would allow Mutaguchi an opportunity to regroup and reorganise his forces. The Allied advance was remorseless and every effort was made to destroy the enemy before he could get across the Chindwin to replenish and dig in. The heavy casualties incurred by the Japanese in battle were made worse by failures in supply, which meant that Japanese soldiers were dying of hunger-induced exhaustion. For the first time in the whole Burma conflict they started to surrender in sufficient numbers to give the Allies a decent intelligence picture based on more than observation and interpretation. The morale of the Burma Area Army units was battered, but by no means destroyed, and British, Indian and African troops still faced a lot of hard fighting. There was, however, clearly no realistic prospect of a Japanese recovery. Allied morale continued to improve as Japanese spirits sank and even if Gen. Mutaguchi had miraculously found a means of spiriting his troops out of harms way and into safe quarters with ample food and medical supplies, there was no means of rebuilding his army as a fighting force. Japanese factories could not produce the guns, armour and small arms to replace those lost in battle or abandoned in the retreat, and Japanese society could not provide the manpower. Even if these things had been possible, there was no time to rain replacements and no shipping to get them into the fight.

At the start of the campaign the Burma Area Army was no longer the confident and competent force it had been in 1942, but by the end of the campaign it was a mere shadow of its former self. If the troops expected the supply situation to improve as they withdrew to their starting positions, they were to be sadly disappointed; airstrikes and sabotage operations had crippled communications all the way to the Thai border. Increasing numbers of administrative and supply troops were now redundant and were being remustered as infantry, but they had little training and in the main no experience of any value; many of them had no rifles and those who did had precious little ammunition.

The U-Go offensive was the only major initiative of 1944. In the Pacific theatre, Japan was on the back foot as American forces advanced from one island to another, mounting air raids against the Japanese homeland with consequent damage to industry and civilian morale. Losses to commercial shipping had mounted steadily since mid-1942 and were impossible to replace, so it was, therefore, increasingly difficult to get the limited materials that industry could produce to where it needed to be right across a vast perimeter stretching through the Pacific and South Asia to Burma.

Defeat made the survivors less confident of eventual victory and, with declining morale from late 1944 onward, it became easier for the Commonwealth forces to take prisoners, though most Japanese soldiers were still fighting with incredible determination. Although the intelligence and planning staffs of Fourteenth Army were keen to have POWs, several factors precluded this: the determination of so many Japanese soldiers to fight on to the bitter end; the practice of having to pound each enemy position to dust to make progress; and an unwillingness among Commonwealth troops to take prisoners given the general experience of the campaign. It was common knowledge that the Japanese generally would not take POWs in Burma and, when they did, they almost invariably treated them with great cruelty wounded men left behind in action were often murdered for sport. The situation was not much better for INA troops. Indian soldiers who had not deserted to the enemy were not inclined to have much respect for those who had.

The failure of the U-Go offensive had a political impact in Burma and India. The Japanese occupation in Burma was clearly not going to last very much longer and even elements that had been strongly opposed to colonial status before the war started to make overtures to the British with a view to being on the right side when the war came to an end. In India the British had kept close control of the media and the INA had not figured prominently, other than as renegades who had betrayed their word and who had been duped and used by the Japanese. The political subtext was that the defeat of the British would simply have meant a rather more oppressive rule from Japan, and that brave and loyal Indian soldiers had been in the forefront of a struggle to protect their country from a rapacious enemy.

The direct threat to India had been removed and the Japanese were being driven from Indian soil in Manipur. This was a major boost to pro-British sentiment. This was more important in much of India than is generally realised today; not all Indians were in favour of the Indian National Congress campaign for independence. At the time it was significant both in British India and in the much larger area of the Princely States. Many people in the latter and not just the princes themselves were happy at the prospect of a massive Indian union imposing a single central authority on the many countries which were, at least notionally, independent of British rule.