Violent Borders

Refugees and the

Right to Move

Reece Jones

This eBook is licensed to z z, zz@gmail.com on 11/19/2016

First published by Verso 2016

Reece Jones 2016

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-471-3 (HB)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78663-183-1 (EXPORT)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-472-0 (US EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-473-7 (UK EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

The Library of Congress Has Cataloged the Hardback Edition as Follows:

Names: Jones, Reece, author.

Title: Violent borders : refugees and the right to move

/ by Reece Jones.

Description: London, UK ; Brooklyn, NY : Verso,

[2016] | Includes

bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016019159 | ISBN

9781784784713 (hardback : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Emigration and immigrationSocial

aspects. | Emigration and

immigrationGovernment policy. | Border security

Social aspects. |

Freedom of movementSocial aspects. | Refugees

Government policy.

Classification: LCC JV6225 .J66 2016 | DDC 325

dc23

LC record available at

https://lccn.loc.gov/2016019159

Typeset in Sabon by MJ & N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall

Printed in the UK by CPI Mackays

This eBook is licensed to z z, zz@gmail.com on 11/19/2016

Contents

This eBook is licensed to z z, zz@gmail.com on 11/19/2016

The question that drives this book, why states are often concerned with limiting the movement of the poor, was inspired by the work of James C. Scott. Scott writes, in the introduction to Seeing Like a State, that he began working on the book with the question of why the state has always seemed to be the enemy of people who move around. He notes that nomads and pastoralists (such as Berbers and Bedouins), hunter-gatherers, Gypsies, vagrants, homeless people, itinerants, runaway slaves, and serfs have always been a thorn in the side of states. Efforts to permanently settle these mobile populations (sedentarization) seemed to be a perennial state projectperennial because it so seldom succeeded. Although Scott writes that this question ended up being a road not taken for himhis book instead focuses on why mega-planning projects by states often failhis work inspired me to investigate it here.

This book has benefited from the comments and insights of dozens of people over the three-year period in which I conceived of and wrote it. First and foremost, I want to thank my partner, Sivylay Kham Jones, and my children, Rasmey and Kiran, for their support during the research and writing process. They traveled with me to several research sites and gave me the time to write the book. Thanks also to my brother, Brent, for reading and editing the entire draft and my parents, Celia and Wally, for their support and encouragement.

My frequent collaborator, Corey Johnson, also read and commented on the entire book, provided feedback throughout the research and writing process, and traveled with me during the field research in Melilla, Spain, and Nador, Morocco. Sections of are derived from a coauthored paper with Corey Johnson entitled Border Militarization and the Rearticulation of Sovereignty, which was published in the Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. It is used here with permission. Jill Williams, Lynn Cochran, and John Padwick read parts of chapters at different stages of writing. Julius Paulo created the global border walls maps. Thanks to Audrea Lim and the folks at Verso for believing in this project and shepherding it to publication.

Several chapters received valuable feedback at workshops and conferences. was presented on September 26, 2014, at the Borders and Globalization Conference in Ottawa, in revised form on May 21, 2015, at the Department of Geography at the University of Oulu in Finland, and on October 15, 2015, in the International Cultural Studies Lecture Series at the East-West Center in Honolulu. Thanks to lisabeth Vallet, Fred Shelley, Travis Gliedt, Emanuel Brunet-Jailly, Victor Konrad, Lauren Martin, and Nandita Sharma for the invitations to speak. Thanks to Oliver Belcher, Simon Dalby, Michael Dear, Anssi Paasi, Darren Purcell, William Walters, and the audiences generally for insightful questions and comments on the presentations. Thanks to Michael Eilenberg for inviting me to the Klitgrten writers retreat in June 2014. The week of the midnight sun in Skagen, Denmark, proved to be a crucial period of writing and reflection that finally gave this project a direction. Thanks also to the fellow Skagen School members Zach Anderson, Erin Collins, Jason Cons, Mike Dwyer, Christian Lentz, Christian Lund, Duncan McDuie-Ra, Jonathan Padwe, and Nancy Lee Peluso for their feedback on my proposal.

This book is based on field research that was facilitated by colleagues and research assistants. Joe Heyman provided valuable advice and connections during my time in El Paso, Texas, in March 2011. Thanks to Riton Quiah for his work in Bangladesh and India in 2006 and 2007 and Namareq Younus for assistance in Palestine in 2010. John Padwick was an amazing source of knowledge about the Midlands Revolt during a research trip in May 2014. My dad and Steve Burnley were wonderful traveling partners on that trip. Mimoun Attaheri, Marcelo Di Cintio, Xavier Ferrer-Gallardo, and Said Saddiki provided useful contacts and information in Morocco and Melilla in November 2014 and March 2015.

Thanks to the International College of Seville for hosting me during my stay in Seville. Thanks also to my colleagues in the Department of Geography at the University of Hawaii at Mnoa, who believed in this project and supported me through course releases and research funds. Mahalo! Any errors that remain are mine.

This eBook is licensed to z z, zz@gmail.com on 11/19/2016

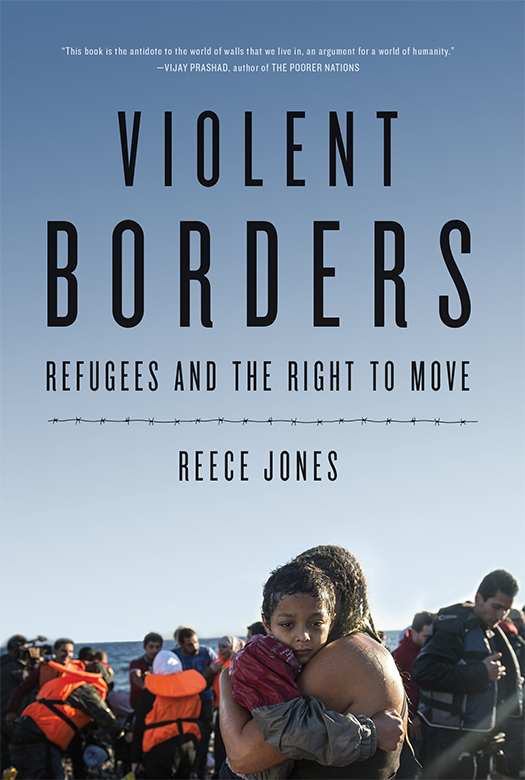

In November 2014, I led a weekend trip to Morocco for American students studying in Spain. It was rainy on the day we took the ferry across the Strait of Gibraltar from Algeciras to Tangier. It was too wet for the first event on our itinerary, a dromedary ride, but our Moroccan guide promised to get the students on a camel at the end of the day, before we took the ferry back to Spain. My students might have imagined a journey through the vast sands of the Sahara, but the reality was three scruffy animals in a waterfront parking lot in the rundown outskirts of Tangier.

As soon as our bus, with its EU license plates, arrived at the lot, fifteen or twenty Moroccan youths, roughly the same age as the American students, surrounded the vehicle, peering underneath it. Most of the students, focused on the animals, did not even notice the commotion, but one of them thought the boys soccer ball was stuck under the bus and bent down to try to help them find it. The Spanish driver and his Moroccan assistant tried to shoo the boys away. It quickly became apparent that the boys were trying to climb under the bus and inside the engine compartment. The driver, helpless and exasperated, gave up and got back behind the wheel. Every minute or two he honked the horn, encouraging the students to hurry up.