ALSO BY T. R. REID

Copyright 2017 by T. R. Reid

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

PROLOGUE: EVERY THIRTY-TWO YEARS

The members of the U.S. Senate rose to their feet and erupted into cheers, handshakes, and hugs on September 7, 1913, to celebrate final passage of the Underwood-Simmons Tariff Actthe statute that created Americas federal income tax. Determined to milk the moment for maximum political benefit, President Woodrow Wilson held a formal signing ceremony at the White House and told the assembled reporters he was proud to be present at the creation of this highly popular tax.

Back then, the newly minted federal income tax was popular with almost all Americans because hardly any had to pay it. The tax we love to hate today was initially aimed squarely at the silk-suit-and-satin-gown setthe Astors and Vanderbilts, the Morgans and Rockefellers. Only the richest smidgen of the population had to file a return, and even for them the top tax rate was just 7%. Over the next nine years, Congress tinkered with the tax regime, each year passing a new internal revenue code with exemptions and exclusions; the deduction for charitable contributions, for example, was added in 1917. The top rate went up sharply to pay for World War I and then came down again. Eventually, in the Internal Revenue Code of 1922, the structure of the federal income tax was essentially set. There were new revenue acts every few years1932, 1939, 1946but the basic system stayed in place for three decades.

By the 1950s, everyone agreed that the Internal Revenue Code was a complex, confusing, contradictory mess. The new president, Dwight Eisenhower, demanded reformand Congress obliged with a complete rewrite: the Internal Revenue Code of 1954. Among much else, it set the deadline for filing your income tax return on April 15. This code stayed in place for three decades, but almost every year Congress, of course, added exclusions and credits and allowances in a haphazard fashion.

By the mid-1980s, the code was such a voluminous, complicated monster that a conservative Republican president and a liberal Democratic Speaker of the House agreed to another complete rewrite: the Internal Revenue Code of 1986. The economists loved this one; it was a comprehensive revision based on the most fundamental principle of sound tax writing.

Theres a pattern here. In the thirty-two years from 1922 to 1954, the Internal Revenue Code became such a chaotic muddle that it had to be replaced. In the thirty-two years from 1954 to 1986, history repeated itself, and once again the Internal Revenue Code had to be rewritten.

It has now been three decades since the last revision. Everyone agrees once again that our nations basic tax law has become a fine mess: so absurdly complex, so byzantine, that it has to be completely revised. Following the historical patternevery thirty-two yearsthe next major revision should come in 2018. Which means Congress and the president have to start working in 2017 to revamp the Internal Revenue Code.

But what should be in this new tax code? Can we make the U.S. tax system simpler, fairer, and more efficient? The answers: yes, yes, and yes. Could we cut tax rates and still bring in more revenue? Yes. We know this because there are good models all over the world to show us how to do it. Other rich countries like oursadvanced, high-tech, free-market democracieshave devised tax regimes that are equitable, effective, and easy on the taxpayer (although theyve made some serious blunders as well). By looking at tax systems around the world, we can learn what the United States should and shouldnt do in writing the Internal Revenue Code of 2018.

1.

POLICY LABORATORIES

D uring one of its periodic bursts of anger at the Internal Revenue Service, the U.S. Congress passed a strict new law requiring the Treasury Department to reduce the complexity of Americas income tax system. In standard congressional fashion, this mandate for simplicityits known as the anti-complexity clausewas included in a massively complex piece of legislation that added some thirty thousand words and scores of complicated new deductions, exemptions, and credits to the bloated multivolume corpus of the nations tax law. If you happen to be browsing through the statute books some restless night, you can find the anti-complexity clause in Subsection IX of subpart (ii) of Section 7803(c)(2)(B) of the Internal Revenue Code.

Its classic: Congress decides to reduce the complexity of our tax code by making it even more complex. It might be funny if the whole taxpaying process in America werent so maddeningly expensive, inefficient, and time-consuming. At the same time Congress took that principled stand in favor of simplicity, it also added a clausethat would be Section 7803(c)(2)(B)(ii)(III)requiring that Treasury file a report each year on the overall cost of the income tax regime. The reported burden on U.S. taxpayers turns out to be no laughing matter.

In 2015, the government estimates, American taxpayers spent just over six billion hours preparing and filing their income tax returns. They paid $10.1 billion in fees to the booming tax-preparation industry and another $2 billion for tax software programs (programs that still require hours of work for the typical taxpaying household). For an American household earning the median family incomeabout $55,000the average is more than thirty hours per year gathering documents and filling out forms. Tens of millions of Americans have to spend the weekend before April 15a lovely spring interlude when they should be out on the golf course or at the kids soccer gametearing their hair out over instructions like this gem from IRS Form 1041: Go to Part IV of Schedule I to figure line 52 if the estate or trust has qualified dividends or has a gain on lines 18a and 19 of column (2) of Schedule D (Form 1041) (as refigured for the AMT, if necessary).

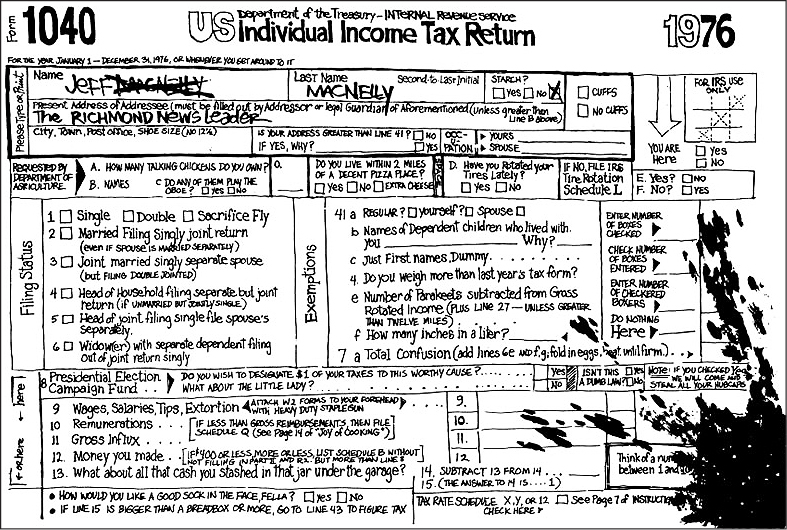

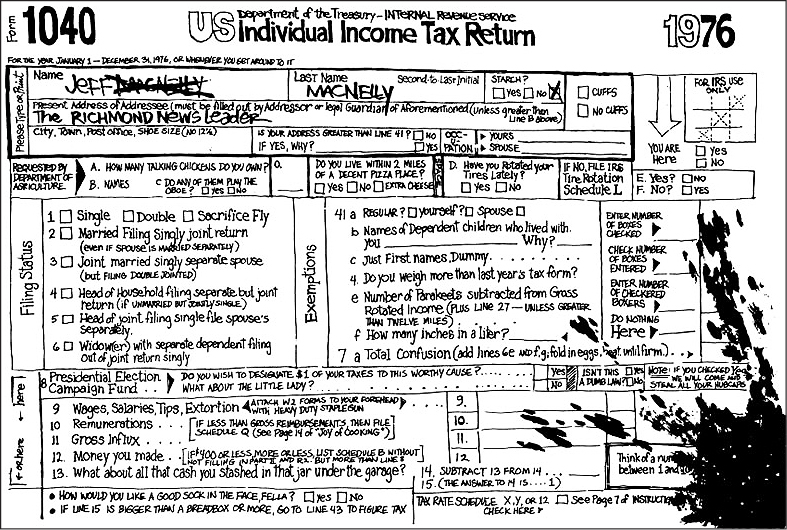

T HE CARTOONIST J EFF M AC N ELLY used to offer a satire of this process every April 15:

Visit bit.ly/2mMukOA for a larger version of this image.

It doesnt have to be this way.

If you walk down the street in London, Tokyo, Paris, or Lima, you wont see an office of H&R Block or any similar firm; in other nations, people dont need a tax-preparation industry to file their returns. Parliaments and tax collection bureaus all over the world have done what the U.S. Congress seems totally unable to do: theyve made paying taxes easy.