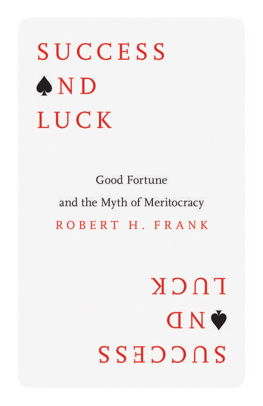

SUCCESS AND LUCK

SUCCESS

ND

ND

LUCK

Good Fortune and the Myth of Meritocracy

ROBERT H. FRANK

Princeton University Press

Princeton and Oxford

Copyright 2016 by Robert H. Frank

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press,

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

Cover design by Will Brown

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Frank, Robert H., author.

Title: Success and luck : good fortune and the myth of meritocracy / Robert H. Frank.

Description: Princeton : Princeton University Press, [2016] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015040858 | ISBN 9780691167404 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Economics. | FortuneEconomic aspects. | SuccessEconomic aspects. | Merit (Ethics)Economic aspects. | EconomicsSociological aspects. | EconomicsPsychological aspects.

Classification: LCC HB71 .F69584 2016 | DDC 650.1dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015040858

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in ScalaOT

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Luck is not something you can mention in the presence of self-made men.

E. B. WHITE

Fifth Philosophers Song

A million million spermatozoa

All of them alive;

Out of their cataclysm but one poor Noah

Dare hope to survive.

And among that billion minus one

Might have chanced to be

Shakespeare, another Newton, a new Donne

But the One was Me.

Shame to have ousted your betters thus,

Taking ark while the others remained outside!

Better for all of us, froward Homunculus,

If youd quietly died!

ALDOUS HUXLEY (1920)

CONTENTS

PREFACE

How important is luck? Few questions more reliably divide conservatives from liberals. As conservatives correctly observe, people who amass great fortunes are almost always extremely talented and hardworking. But as liberals also rightly note, countless others have those same qualities yet never earn much.

In recent years, social scientists have discovered that chance events play a much larger role in important life outcomes than most people once imagined. In Success and Luck, I explore the intriguing and sometimes unexpected implications of those findings for how best to think about the role of luck in life.

My original working subtitle for the book was A Personal Perspective. I chose it out of concern that some readers might object if not given sufficient notice that my story includes numerous accounts of my own experiences with chance events. But my editors at Princeton persuaded me that A Personal Perspective could lead many to mistake the book for an autobiography, which Success and Luck is not. Their worry, unstated but no doubt valid, was that autobiographies of noncelebrities attract few readers.

Because Ive long argued that the market systems of most developed economies are now far more meritocratic than at any time in history, I was reluctant at first to embrace Princetons proposed alternative, Good Fortune and the Myth of Meritocracy. My concerns were confirmed by the reaction of a longtime colleague when I showed him a mockup of the books cover. Why SHOULDNT companies hire the most qualified applicants? he asked. I assured him that I was as vehemently opposed to cronyism as he was.

As a practical matter, of course, no system could ever be perfectly meritocratic. But my eventual decision to go with Good Fortune and the Myth of Meritocracy had little to do with concern about whatever vestiges of cronyism and class privilege might persist. Rather, it was because I believe the rhetoric of meritocracy has caused enormous harm.

The term itself was coined in 1958 by the British sociologist (and later lord) Michael Young in a scathing satire of the British educational system. In The Rise of the Meritocracy, he argued that encouraging successful people to self-aggrandizingly attribute their success solely to their own efforts and abilities would actually make things worse, on balance. Young was chagrined that the term hed coined as a pejorative had been so quickly co-opted as an adjective of praise.

In societies that celebrate meritocratic individualism, saying that top earners may have enjoyed a bit of luck apparently verges on telling them that they dont really belong on top, that they arent who they think they are. The rhetoric of meritocracy appears to have camouflaged the extent to which success and failure often hinge decisively on events completely beyond any individuals control. In his commencement address to Princeton Universitys 2012 graduating class, for example, Michael Lewis described the improbable chain of events that helped him become a rich and famous author:

On the basis of his experiences at Salomon, Lewis published his 1989 breakout best seller describing how the new wave of Wall Street financial maneuvering was transforming the world:

The book I wrote was called Liars Poker. It sold a million copies. I was 28 years old. I had a career, a little fame, a small fortune and a new life narrative. All of a sudden people were telling me I was born to be a writer. This was absurd. Even I could see there was another, truer narrative, with luck as its theme. What were the odds of being seated at that dinner next to that Salomon Brothers lady? Of landing inside the best Wall Street firm from which to write the story of an age? Of landing in the seat with the best view of the business? Of having parents who didnt disinherit me but instead sighed and said do it if you must? Of having had that sense of must kindled inside me by a professor of art history at Princeton? Of having been let into Princeton in the first place?

This isnt just false humility. Its false humility with a point. My case illustrates how success is always rationalized. People really dont like to hear success explained away as luckespecially successful people. As they age, and succeed, people feel their success was somehow inevitable. They dont want to acknowledge the role played by accident in their lives.

The New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof has often sounded a similar theme:

One delusion common among Americas successful people is that they triumphed just because of hard work and intelligence.

In fact, their big break came when they were conceived in middle-class American families who loved them, read them stories, and nurtured them with Little League sports, library cards and music lessons. They were programmed for success by the time they were zygotes.

A dark side of this delusion, Kristof notes, is that those who are oblivious to their own advantages are often similarly oblivious to other peoples disadvantages:

The result is a meanspiritedness in the political world or, at best, a lack of empathy toward those strugglingpartly explaining the hostility to state expansion of Medicaid, to long-term unemployment benefits, or to raising the minimum wage to keep up with inflation.

Kristof recounts the life history of Rick Goff, a friend from his small hometown in Oregon. Shortly after Goffs mother died when he was five, his alcoholic father abandoned Goff and his three siblings to raise themselves. People who knew Goff describe him as a loyal friend. He was also said to have had a terrific mind but did poorly in school because of an undiagnosed attention deficit disorder. He dropped out before finishing the tenth grade, then worked in lumber mills and machine shops before going on to become a talented painter of custom cars. But after seriously injuring his hand in an accident, he struggled to get by on disability payments and odd jobs. His untimely death at sixty-five in July 2015 was triggered by his inability to afford a crucial medication because hed spent $600 to bail his ex-wife out of a financial emergency.

Next page

ND

ND