All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Doubleday, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Ltd., Toronto.

DOUBLEDAY and the portrayal of an anchor with a dolphin are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Names: Goyal, Nikhil, author.

Title: Schools on trial : how freedom and creativity can fix our educational malpractice / by Nikhil Goyal.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015023598 ISBN 9780385540124 (hardcover) ISBN 9780385540131 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Alternative educationUnited States. School improvement ProgramsUnited States. School environment.

Classification: LCC LC46.4 .G69 2016 DDC 371.04dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015023598

How could youths better learn to live than by at once trying the experiment of living?

Introduction

On most mornings, millions of young people depart from their homes and travel by cars and yellow buses to drab-looking, claustrophobic buildings. Here, they will be warehoused for the next six to seven hours. Some are greeted by metal detectors and police officers, others by principals and teachers. In the hallways, security cameras keep tabs on them. Every forty minutes, they are shepherded from room to room at the sound of a bell. They sit in desks in rows with twenty to thirty other people of similar age, social class, and often race. They are drilled in facts and inculcated with specific attitudes and behaviors. They are motivated to participate in this game by numbers, letters, prizes, awards, and approval of various authority figures. If they get out of their seat, talk out of turn, or misbehave, they risk being drugged to induce passivity. Their day is preplanned for them. In a world of increasing complexity, there is little critical thinking expected of them. To succeed, orders and rules must be followed. The fortunate ones have recess. During lunch, many have little choice but to consume unhealthy, unappetizing food. At the end of the day, they return home bone tired. There, they are forced to complete a few more hours of free labor, known as homework. They follow the almost exact same routine five days a week, 180 days a year, for thirteen years, until they are set free or begin another game called college with its own set of absurd rules.

This is what is known as school for most children. If a sensible race of aliens paid a visit to our planet, they would think we are crazy. It still amazes me how most people dont find it particularly odd that you have this small subset of the populationpeople from ages five to eighteenwho are locked up in buildings for seven hours a day, while most of the rest of us are living and learning in the world.

During a visit to an alternative, progressive school, I remember someone once asking me, So when did you realize this whole compulsory school system was bullshit? There wasnt one specific moment or event that triggered my awakening. It was more of a gradual change in beliefs over some time.

In the summer of 2010, my family and I moved from Hicksville, New York, to Woodbury, a couple of towns over on Long Island. I transferred from the Bethpage to the Syosset schools, one of the highest-ranking and wealthiest school districts in the country. That fall, I enrolled as a sophomore at Syosset High School. There are more than two thousand students in the school. Almost three-quarters are white, about one-quarter is Asian, and just 4 percent are black and Latino.

Every school morning at 6:30 a.m., my alarm clock began to blare. After I mustered enough courage to crawl out of bed, I dragged myself into the bathroom to get ready, wolfed down my breakfast, and caught the bus. I usually plopped into a seat in the back and nursed my sleep-deprived self by dozing off for the next twenty minutes or so. Once I arrived at school, my way-too-energetic principal greeted me at the door. Then the social ostracism began. Each clique of each grade generally gathered in a different part of the building: the football players and cheerleaders near the science wing, some of the nerds in the student lobby trying to squeeze every last second of studying in before the bell. I trudged to my first-period class, like thousands of my fellow inmatesI mean studentswhile fluorescent lights beamed down on my half-closed eyelids.

For the next seven hours, it was as if I were on a conveyor belt. At each station (class), my head got filled with content. Every forty minutes I was told to stop what I was doing, get up, and find the next classroom that I would be imprisoned in, with a few minutes of rest in between if I was lucky. By the end of the nine-period exertion, I was mentally and physically drained.

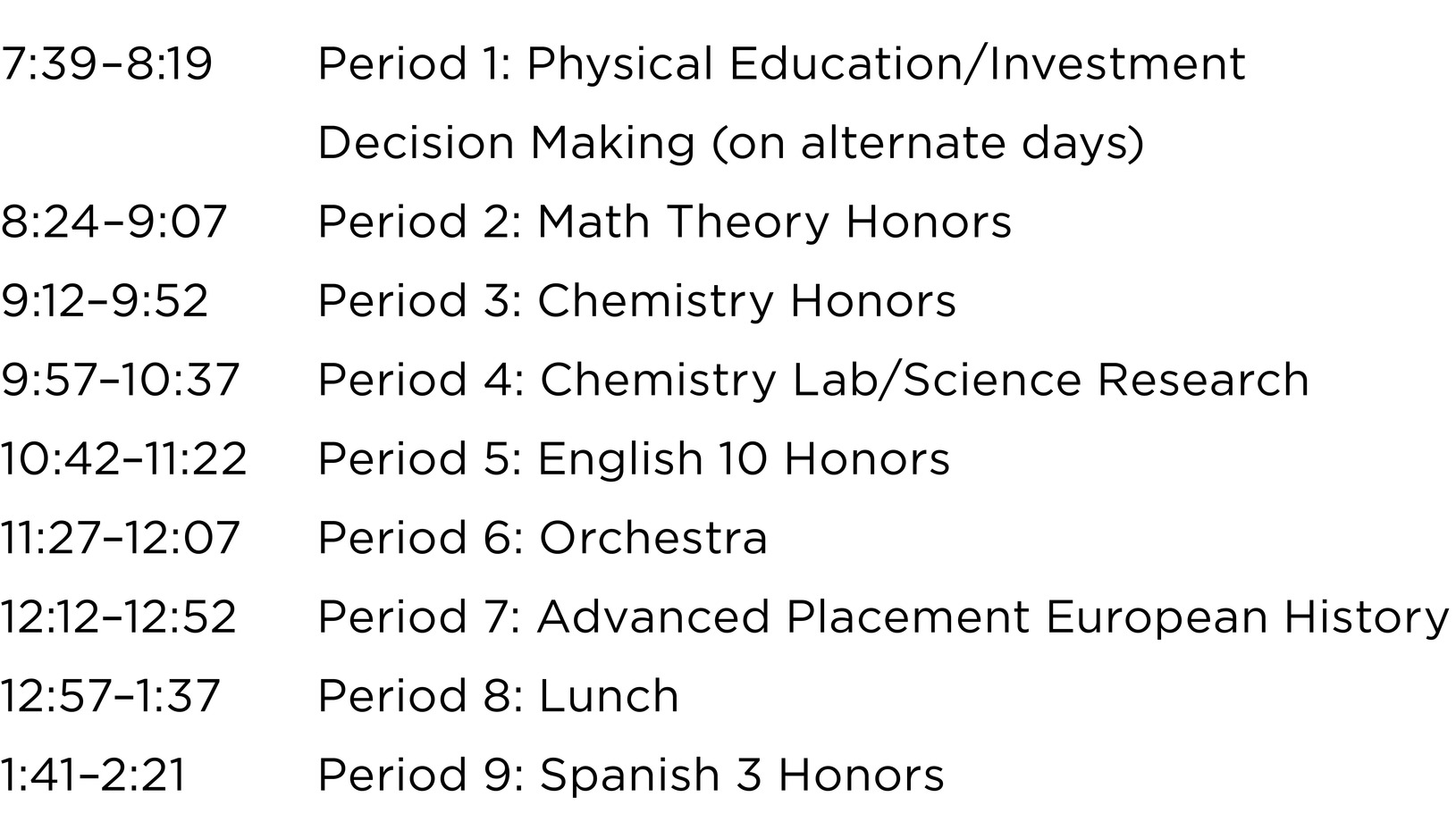

Take a look at my sophomore year schedule:

In the entirety of a seven-hour day, I had one forty-minute lunch break and five-minute breaks between periods, which were spent bolting to my next class. With the way the building was laid out, classrooms were often very far apart from one another.

In high school, I played the game. I got mostly As and a few Bs to set myself up in case I eventually wanted to have a shot at getting accepted into a prestigious college. And so I tolerated the endless drudgery of my classes. Unpleasant memories of my chemistry class, in particular, are still fresh in my mind. Our teacher would just lecture at us for most of the period, and we, the students, were supposed to copy down notes mindlessly. There was little interaction or engagement. And the exams were heavily recall based. Honestly, I couldnt tell you what I learned in that class, because I have forgotten it all. When we did laboratory exercises, it felt like a mockery. The labs were scripted. We were told to follow the precise directions given to us. We were penalized if we didnt get the correct answer. The whole charade went against the most fundamental tenets of science: experimentation and failure.

In my English classes, we often received a reading assignment to complete that evening, and the next day, we were quizzed on the material. Five-question quizzes with each question worth twenty points. Some of the questions revolved around very trivial details: What was a character wearing? What time of day was it? Its almost as if my teachers were involved in a plot to help us develop a fervent hatred for reading. When I was younger, I would spend my days absorbed in novels and short stories, and I sometimes came up with my own. Being forced to read these books and be subjected to these meaningless tests are why I dont enjoy reading fiction today. I love reading nonfiction books about current affairs, however. Not coincidentally, I cant recall reading more than two or three nonfiction books in class throughout my thirteen years of schooling.