Marxism with Soul: On the Life

and Times of Marshall Berman

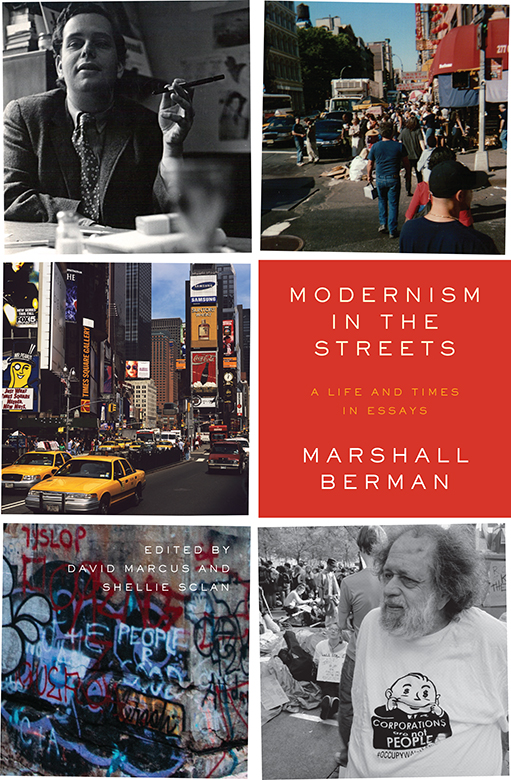

Marshall Berman was born in the South Bronx in 1940. Over the next three decades, he watched his lower-middle-class neighborhood turn to ruin. Between 1948 and 1972, Robert Moseswho years later became the Faustian villain of Bermans All That Is Solid Melts into Airbuilt the Cross Bronx Expressway. It ravaged the South Bronx, cutting it up into bits and pieces and bombing out other areas completely, including much of Bermans own neighborhood, Tremont. In the 1970s, the less systematic destruction began. New York City was broke and its outer boroughs were in a state of neglect and disrepair. The Bronx finally made it into the media, as Marshall recalled in an essay about the 70s. The headline: The Bronx Is Burning!

The self-destructive tendencies of New York Cityand, more generally, of modern urban lifewere to become the central preoccupation in Bermans work. His first book, The Politics of Authenticity (1970), took eighteenth-century Paris and its two most brilliant thinkers, Montesquieu and Rousseau as a case study for what culminated in the revolutionary violence at the end of the century. All That Is Solid, which came twelve years later, was something less and something more. It marked the end of a promising, though contained, academic career in the vein of his college and early graduate school mentorsPeter Gay, Lionel Trilling, Isaiah Berlinand the blossoming of a startling and radical new voice in social criticism. Tracing an arc of violence and destruction from Goethes Faust to New York Citys Moses, Berman argued that modernism, when coupled with the toxic tendencies of industrial capitalism, wreaked havoc on mans psychic and spiritual life as well as his social and economic conditions.

Both works and the many essays that came before and after also insisted there was another side of modern life. A figure like Robert Moses, eschewing the humanist impulses of city life and modernist aesthetics, sought to rid New York of its creative chaos. But the modern city could also be a place for human creativity and rebirth and Berman was drawn to those figures who embodied this vision. From Marx to Lukcs, Baudelaire to Run-DMC, the intellectual and creative brilliance of modern urban life, fractured and chaotic as it is, could help build us anew. From alienation came freedom, and from modernitys ruins came new life. All that is solid melts into air was Marx and Engelss lament about what had happened to life under capital; for Berman this was also a credo for how to rebel against it.

The opening chapter of Politics of Authenticity is titled The Personal is Political. Ive always wondered about this titleit being, even then, somewhat of a flat-tire turn of phrase. But I think what Berman meant was something more nuanced: that the political should be personal. As Corey Robin and others have pointed out, Bermans historical and philosophical narratives were almost always suffused with personal trauma. This, perhaps, reached its fullest expression in All That Is Solid, where he moved from eighteenth-century Paris to his own midcentury New York, and also in his later essays collected in Adventures in Marxism. But his turn to the personal went well beyond the fact that he was now writing from his home turf; it was, rather, an attempt to make our politics more personal, more felt.

For Berman the failure of modern capitalismin both its industrial and postindustrial phaseswas as much about the emotional suffering it caused as its unequal distribution of goods and services. This was why Berman found the young Marx, who writes of alienation, and the young Lukcs, who writes of a particular form of alienation (reification), so appealing. Their ideas were ways of explaining what Berman already suspected was wrong with the world he inhabited: It was not so much that his father was a failed garment-district middleman but that his father had suffered the psychic costs of this failure.

This personalization of Marx and of social criticism more generally was what lent Bermans thinking its poignant erudition. It is what also drew him to the humanist side of the Left. Even when capitalism was highly successful, Berman wrote, Marx helped him realize that it could be humanly disastrous, inflicting upon people insult and injury by treating them as nothing more than a commodity. The great injustice of modern life was not just the inequalities it produced but also the high tax they placed on us: the ways in which they limited our range of expression as well as our formal freedoms, our libido as well as our workweekthe ways they helped turn whole neighborhoods into expressways.

One does not always practice what one preaches. But it was precisely this sensitivity to human feeling that made Berman so lovely as a person. He cared. His generosity came casually to him. He lent me Peter Gays Weimar Culture (a reason why I went to graduate school). He read a fellow editors four-year-old undergraduate thesis in an afternoon and then offered detailed notes and corrections. He even tried, unsuccessfully, to get Michael Walzer to listen to Bob Dylan.

A common refrain at Dissent meetings is, So what do we think about this? Berman often phrased it, So how do we feel about this? When I was at something of a romantic impasse several years ago, he steered our lunch conversation away from edits on a review of his to narrate a comically failed early romance.

That reviewone of his late classicstold the story of Ka, Blue, and Ipek, the characters that form the sad, mostly unconsummated love triangle that anchors Orhan Pamuks Snow. For Berman, the center of the novel was not the clash between the secular and religious, the modern and the traditional. It was love: love won but also, more commonly, lost. This was our most modern of disasters: the suggestion of freedom, the age of liberation, and yet nothing. We can speak and be heard, touch and embrace, but something about modern life seems to stop us from loving. Ka and Ipek, plotting to escape the religious violence of Anatolia, never catch their train. They dream of a place where they can overcome what keeps them apart. But the currents of history, or at least the currents of Pamuks novel, stop them.

Berman wrote:

In the history of modern culture, the archetypal couple presiding over Kas and Ipeks fantasies and hopes come from the moment of the French Revolution: they are Papageno and Papagena, from Mozarts