ALSO BY JOHN HIRST

Adelaide and the Country, 18701917

Convict Society and Its Enemies

The Strange Birth of Colonial Democracy

The World of Albert Facey

The Sentimental Nation

Australias Democracy

Making Voting Secret

Sense and Nonsense in Australian History

The Australians

Freedom on the Fatal Shore

Places of Democracy

The Shortest History of Europe

Looking for Australia

Published by Black Inc.,

an imprint of Schwartz Publishing Pty Ltd

3739 Langridge Street

Collingwood Vic 3066 Australia

email: enquiries@blackincbooks.com

http://www.blackincbooks.com

Copyright John Hirst 2016

John Hirst asserts his right to be known as the author of this work.

All Rights Reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the publishers.

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Hirst, J. B. (John Bradley), 19422016 author.

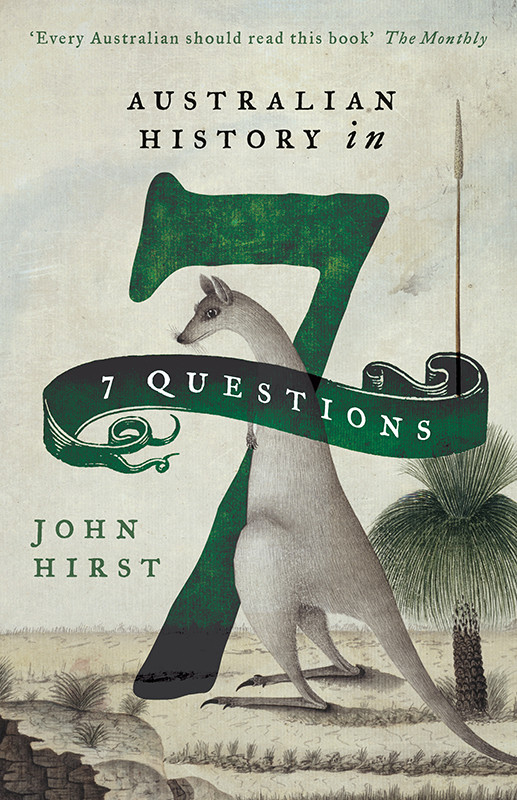

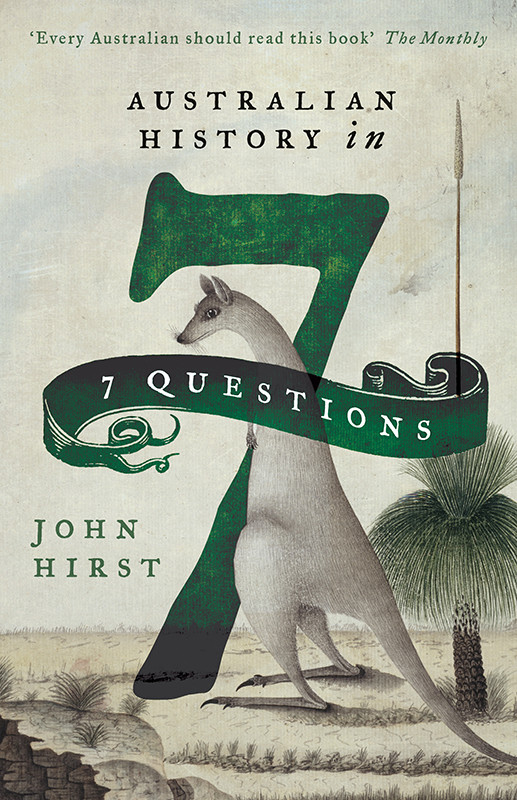

Australian history in 7 questions / John Hirst.

9781863958226 (paperback)

9781922231703 (ebook)

AustraliaHistory. 994

Cover design: Peter Long

Cover images: The Founding of Australia by Algernon Talmage (1937), used with permission of the State Library of NSW (call no. ML 1222); Getty Images.

Map design: MAPgraphics Pty Ltd

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

I know that many people find Australian history dull and predictable. They get too much of it at school and if they are still interested in history at adulthood they turn with relief to The Tudors on the BBC and to the books of Simon Schama, Niall Ferguson or Jared Diamond.

I was conscious of the challenge I faced when a branch of the University of the Third Age in Melbourne asked me to lecture on Australian history. I had lectured with success to several branches on European history, repeating the lectures I gave at university and which became the book The Shortest History of Europe . How could I match that for Australian history? I offered four lectures under the heading Four Questions in Australian History. If there are genuine questions about Australian history, there is something to puzzle over. The history ceases to be predictableand dull. These lectures too were well received, which encouraged me to add a few more questions and make a book in this style.

By this route I have reached the same point as I did when considering how best to present European history. In both cases I have departed from a straightforward narrative in favour of a more thematic treatment. Narrative can make history a good read, but it can also leave unanswered the questions What makes this society distinctive? and Why did its history take this course?

The answers to the questions that this book poses can be read separately. Taken together, I hope they provide as good a guide to Australian society as the more orthodox histories, or an even better one. It is unquestionably a much shorter book than the usual.

I owe a debt to that excellent institution the University of the Third Age for setting me on this path. Lotte Mulligan, who was a colleague when we were both at La Trobe University, now has a second academic life as the organiser of studies at the Stonnington branch of the University of the Third Age. She has been a great supporter of my efforts and the chief urger for this book to be written. To her my thanks.

Question 1 is new territory for me. I am very grateful to Professor Peter Bellwood of the Australian National University, a world expert in this field, for looking over and correcting my chapter. Professor Ann McGrath, also at the Australian National University and a former student of mine, helped me with Aboriginal life in the Northern Territory. I talked over James Belichs book on the Anglo-world with Professor Graeme Davison, and he kindly read Chapter 3.

John Hirst

December 2013

QUESTION 1

WHY DID ABORIGINES NOT BECOME FARMERS?

In the beginning all humankind were hunter-gatherers. About 10,000 BC agriculture was developed independently in a handful of places around the globe. It then spread widely; it came close to Australia, but in Aboriginal times was not established here. The Aborigines remained hunter-gatherers.

The highlands of New Guinea were one of the places where agriculture was developed, but it did not spread far, not even to the whole of the island. China was another place of agricultural invention, and from there it spread south to the Philippines and then west to Indonesia and eastward into the Pacific. So Timor, New Guinea, the Solomons, Vanuatu and Fiji had fields and gardens and settled village life. Australians now call this part of the globe an arc of instability. In prehistoric times these were places of settled life, while the Australian Aborigines remained wanderers.

Gardens came very close to Australia; they were cultivated on islands in the Torres Strait, between Australia and New Guinea. The people here were Melanesian, like the other gardeners in this region, though most spoke an Australian Aboriginal language. As this suggests, the Aborigines of Cape York had close relations with the gardeners of the Torres Strait so close that the fuzzier hair of the Melanesians is found quite a way down Cape York.

The Cape York Aborigines traded and fought with the Torres Strait Islanders. The islanders took heads from the Aborigines they had killed to trade for outrigger canoes from New Guinea. The Aborigines, in turn, traded with the islanders to obtain canoes so they had more sophisticated craft than the bark canoes that were used in other parts of Australia. The Aborigines followed some of the rituals of the islanders: they used drums in their ceremonies and placed the corpses of the dead on platforms. The islanders learnt of the throwing stick, or woomera, from the Aborigines.

In all this exchange the Aborigines learnt about gardens and garden crops, but they did not become gardeners. Sometimes it is said that Australias soil and climate and its plants were not suitable for agriculture, but this argument wont work for Cape York. The soil and climate were the same as on the islands. The women on Cape York dug up the same yams that were planted in gardens in Torres Strait. Coconut trees grow wild in Cape York but were not planted as they were on the islands.

From around 1700 AD the Aborigines in Arnhem Land and the Kimberleys were exposed to rice, one of the standard agricultural crops, first developed in China. The Macassans from the island of Sulawesi in Indonesia sailed each year to the Australian coast to collect trepang, or sea cucumber, which they sold for use in Chinaas a food and as an aphrodisiac. They brought rice to live on during their stay in Australia and to supply to the Aborigines, with whom they wanted to remain on good terms while they camped on their territory. The Aborigines liked rice, and the Aboriginal men who went back to Sulawesi with the Macassans for the off-season saw rice being grown, but the Aborigines did not move to cultivate their own rice. It could be done. The Chinese grew rice in the Northern Territory in European times.