INTRODUCTION

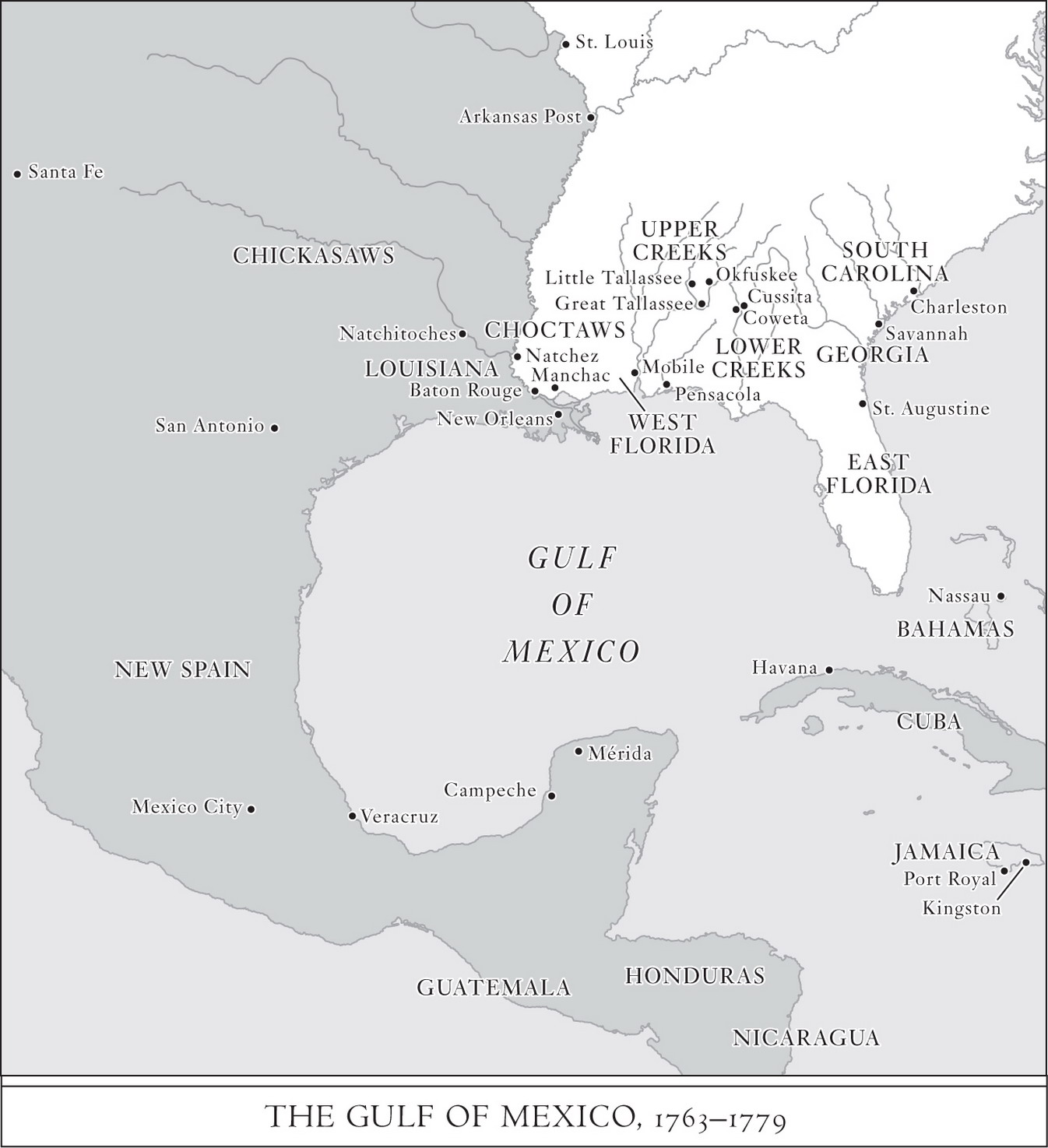

AS THE SKY LIGHTENED in the early morning hours of March 9, 1781, British sailors on a frigate floating at the mouth of Pensacola Bay spotted a fleet heading straight for them. One sailor scrambled high on the mast, straining to see the flag flying over the lead ship. Hoping to see the red, white, and blue of the Union Jack, instead the lookout recognized the bold red and gold stripes of Spanish King Carlos IIIs naval flag. The British frigate fired seven shots, whose thunderous sound warned the people of Pensacola of imminent invasion.

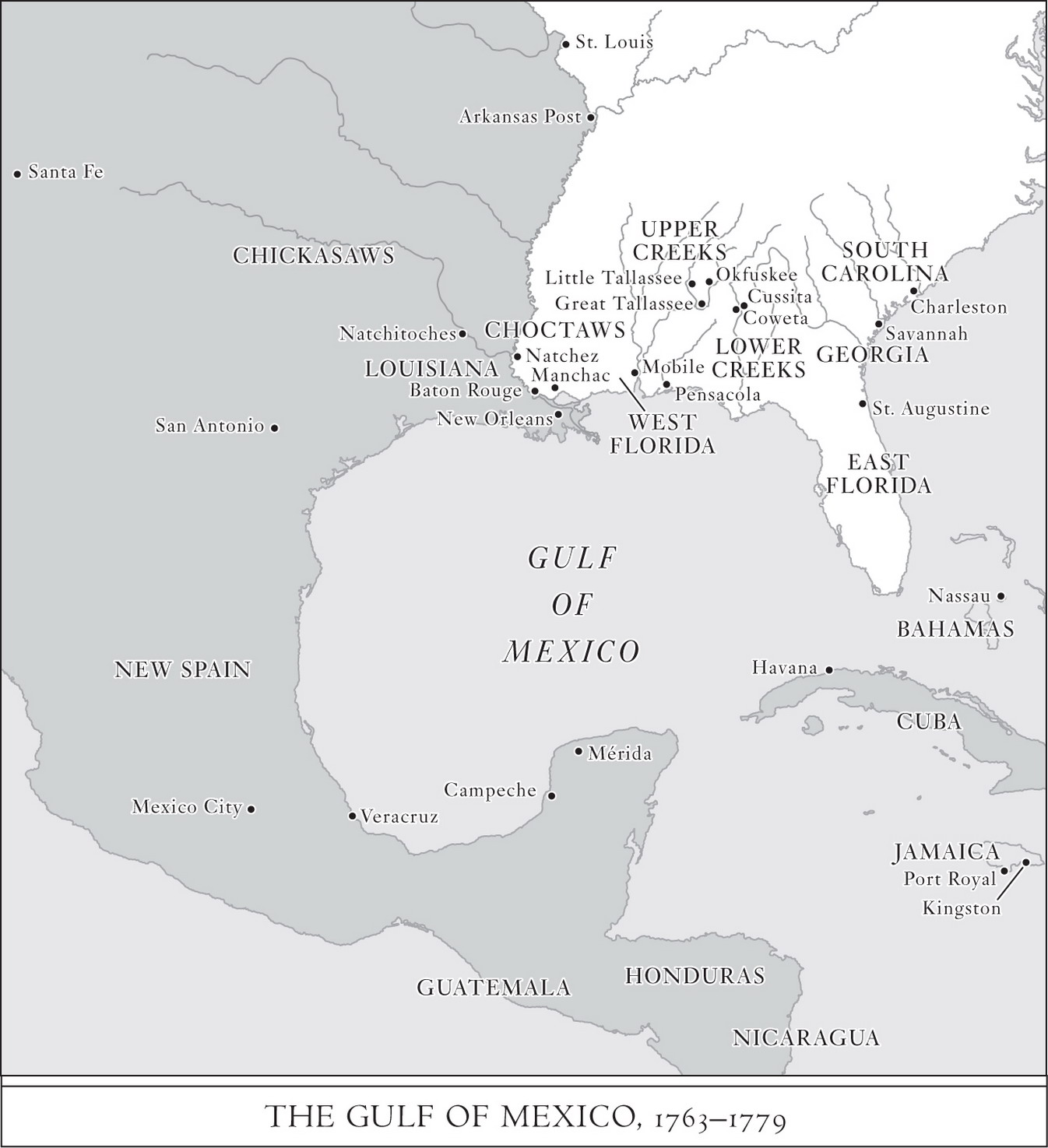

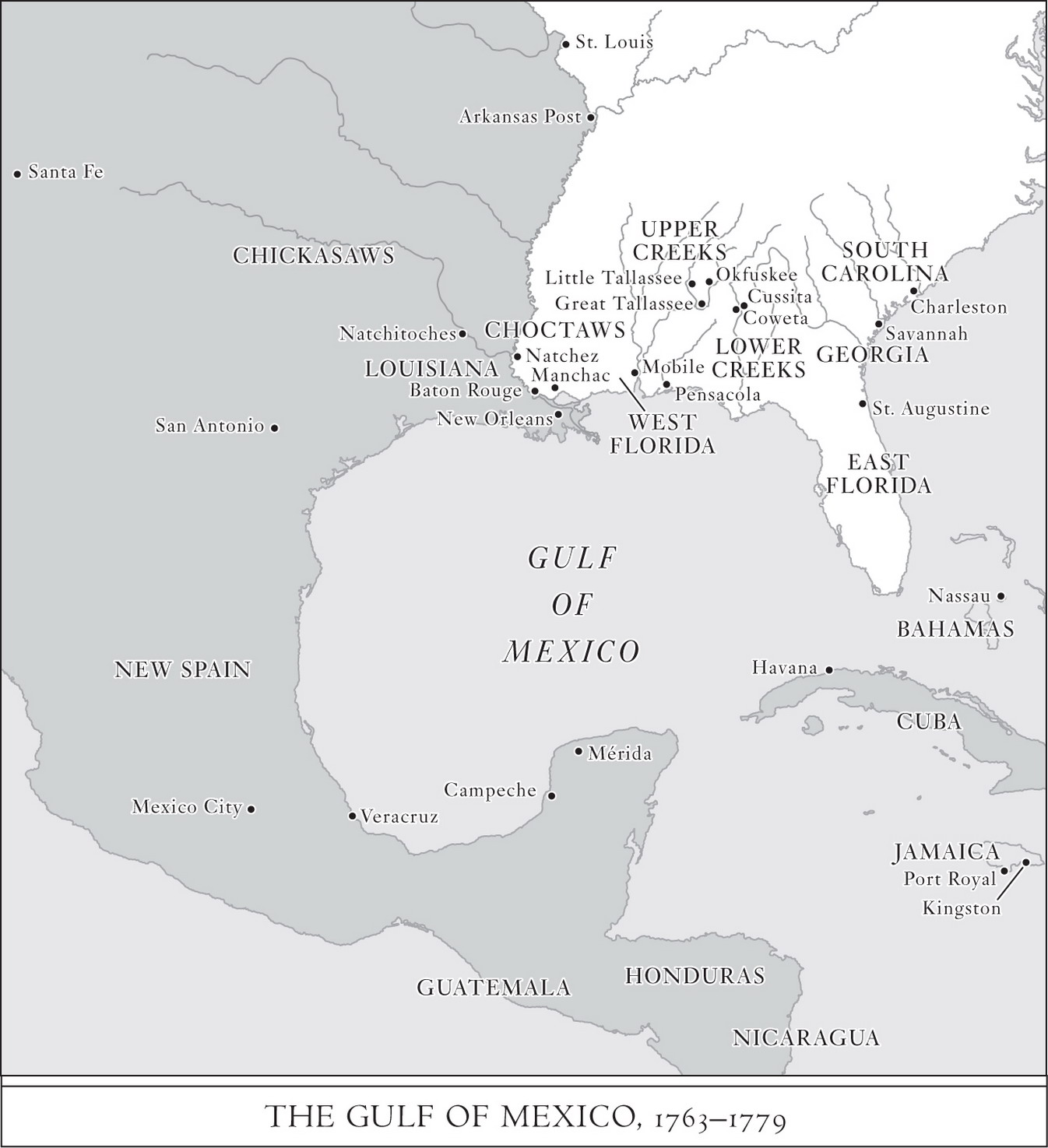

These sailors were not surprised at the Spanish invasionPensacola was the capital of British West Florida and the last line of defense against Spanish conquest of the entire colony. The sailors had only hoped that the Spanish would not arrive before reinforcements. However, readers today might be surprised by this North American battle adjacent to battles of a better-known warthe American Revolution. While histories of the American Revolution include the Marquis de Lafayette and the French fleet at Yorktown, most Americans and even many historians do not know that the Spanish were fighting their own battles against the British at the same time. As Britain tried to put down the rebellion in thirteen of its colonies, it was also defending its other thirteen colonies on the North American mainland and in the West Indies against the Spanish and the French. By invading West Florida, Spain was taking advantage of the distraction of the rebellion to expand eastward along the Gulf of Mexico. For Britain, now on the defensive on two fronts, the prospect of Spanish expansion raised the stakes of the war.

Pensacola, March 910, 1781, with the Spanish fleet off Santa Rosa Island and the British Mentor and Port Royal guarding the Bay. (Toma de la plaza de Panzacola y rendicin de la Florida Occidental a las armas de Carlos III, Ministerio de Defensa, Archivo del Museo Naval, Spain).

Forgotten Stories

The American Revolution on the Gulf Coast is a story without minutemen, without founding fathers, without rebels. It reveals a different war with unexpected participants, forgotten outcomes, and surprising winners and losers.

Although the Revolutionary War was a global war with global causes and consequences, two circumstances following the rebels victory led their story to take center stage as the standard history of the Revolution. The first was the Treaty of Paris, in which the United States and Britain divided the eastern half of the continentand excluded other Europeans and Indians. The second, following the treaty, was the large numbers of Americans settling on lands claimed by Spaniards, Creeks, Chickasaws, Cherokees, and others. The kings of France and Spain entered this global war not because they loved rebellion (much the contrary) but for the same kinds of imperial objectives that had propelled them into previous wars. Although both worried that the rebellion could set a bad example for their own colonies, they were more interested in reversing Britains victories from the Seven Years War of the 1750s and 1760s and protecting and expanding their global empires.

On the Gulf Coast, and indeed for most people, the Revolution seemed to be just another imperial war, another war fought for territory and treasure. As different alliances competed for power, Spanish, British, and French colonists, black slaves, and Indians of many nations were drawn into this multifaceted war. The narrative of the Revolutionary era is more true to its people and more fascinating in its complexity if it includes less familiar regions and peoples and if it encompasses the wars experiences and results in all their diversity.

The war on the Gulf Coast proves two truths often buried by common narratives of the Revolutionary War: that most people chose sides for reasons besides genuine revolutionary or loyalist fervor and that non-British colonists exercised a great deal of influence over the wars outcome. In Virginia, slaves rushed to British lines seeking freedom from their American masters. Near the border of New York and Canada, Mohawk Indian Molly Brant spied for the British, sheltered loyalists in her home, and persuaded men of the Iroquois Confederacy to fight on the British side. She hoped that by supporting the British she could maintain the Iroquois-British alliance and stem the tide of settlers into Iroquoia. Sometimes support was merely for self-preservation. In Vincennes (present-day Indiana), French families came out to welcome American George Rogers Clark with a bottle of wine when he took their town from the British, assuring him of their love of the American rebels. They did the same for the British when they retook Vincennes a few months later, and again brought out the wine when Clark returned, each time hoping to curry favor with whatever military power was ascendant.

This book focuses on the Gulf Coast, from Florida to Louisiana, because of the astounding number of competing interests that came into conflict there. The Gulf Coast was the only site of Revolutionary War battles that was outside the rebelling colonies during the war but soon became part of the United States. The Gulf Coasts war included participants that most people do not think of when they consider the American Revolution: the French and Spanish, who had a centuries-long history in the region; Creeks, Chickasaws, and Choctaws, whose lands spread from the coast deep into the interior of the continent; and people of African descent, whose experiences of enslavement and freedom differed widely and, with the introduction of large-scale plantation slavery, would be changing faster than ever.