Patronage and Power

LOCAL STATE NETWORKS AND PARTY-STATE RESILIENCE IN RURAL CHINA

Ben Hillman

STANFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

STANFORD, CALIFORNIA

Stanford University Press

Stanford, California

2014 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of Stanford University Press.

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, archival-quality paper

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hillman, Ben, author.

Patronage and power : local state networks and party-state resilience in China / Ben Hillman.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8047-8936-3 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. Local governmentChina, Southwest. 2. VillagesChina, Southwest. 3. Social networksChina, Southwest. 4. Patronage, PoliticalChina, Southwest. 5. China, SouthwestPolitics and government. 6. China, SouthwestRural conditions. I. Title.

JS7365.S68H55 2014

320.80951'3dc23

2013041563

ISBN 978-0-8047-9161-8 (e-book)

Contents

Preface and Acknowledgments

One of the great mysteries of contemporary China is how the one-party state has held together through decades of dramatic social and economic change. When I first began to study Chinese politics in the early 1990s it was widely predicted that the Chinese one-party state would be the next domino to fall after Eastern Europe. Specialists on Chinas domestic politics generally agreed that the Communist Party-state was in atrophy as a result of declining legitimacy, widespread bureaucratic indiscipline, and moral decay. During the 1990s the Chinese Communist Party proved its doomsayers wrong by presiding over another decade of reform and dynamic economic growth. However, the very success of Chinas reforms and economic advancement became new grounds for Western specialists to predict the coming collapse of the party-state. Many argued that rapid economic growth and the rise of an increasingly well-educated middle class and more assertive civil society would create irresistible pressures for political liberalization. Indeed, much of the literature on Chinese politics in the late 1990s and early 2000s was preoccupied with identifying the seeds of Chinese democracy and the future shape of a more liberal Chinese state.

Today the Chinese party-state appears increasingly resilient, even in the face of rising economic inequalities, increasing social conflict, and widespread official corruption. Its resilience is the inspiration for this book. As a graduate student in the early 2000s I wanted to understand the institutions and mechanisms that enabled the Chinese party-state to defy predictions of its demise. While the literature on Chinese politics and institutions was growing and new data were becoming available, few scholars had been able to look inside the notoriously secretive Chinese state. I wanted to get inside the black box to examine the internal logic of Chinese officialdom. I decided the best way to approach my subject was to conduct an ethnography of the party-state at the local level, where I could gain access. I began my investigation in a county in southwest China where a local NGO facilitated my participation in a series of environmental and rural development projects. During my first two years in the field I worked as a volunteer and consultant for Chinese and international NGOs, which gave me the opportunity to observe local political processes. I worked on a number of projects in collaboration with officials from various agencies and from various levels from township through to provincial government. I attended government meetings, accompanied officials on site visits, and socialized with officials after hours. Many of the people I worked with became friends. Through my relationships with them and through my observations of everyday politics I learned the unwritten rules of Chinese officialdom. By observing up close political phenomena that are normally only studied from a distance, I have been privileged with the opportunity to shine a light on corners of Chinese politics that are normally obscured from view. This book provides a microcosmic account of how the Chinese party-state operates in the absence of ideology and rule of law.

This book is the product of more than ten years of research. Along the way I have been the beneficiary of guidance and encouragement from many people. Jon Unger was instrumental in helping me to frame my original study and continued to be a most generous mentor as the project evolved. My wife Lee-Anne Henfry has been an extraordinary source of inspiration, ideas, and editorial support. Im also grateful for the sage advice received from Tom Bernstein, Ben Kerkvliet, Andrew Kipnis, Kevin OBrien, Jean Oi, Anthony Saich, and Mark Selden. Many other colleagues have given me much encouragement throughout the project. They include Geremie Barm, Anita Chan, Graeme Smith, Luigi Tomba, and Peter Van Ness. I would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers and the team at Stanford University Press for their extremely helpful suggestions. Last, but not least, I want to thank all the people in China who allowed me to share their stories. To protect them, all names of people and places in this book have been disguised.

INTRODUCTION

Studying the Local State in China

One of the biggest puzzles about contemporary China is how the party-state has held together after more than three decades of rapid social and economic change. While analysts continue to question the states capacity to maintain growth and stability without deeper political reform, in recent years the authoritarian state has looked increasingly resilient, even in the face of rising inequality, increasing numbers of social conflicts, and widespread official corruption. Developments in China continue to defy theories of political change, especially the conventional wisdom that sustained and rapid economic growth will lead to pressures for political liberalization and democratization. Indeed, previous models of political development appear less and less useful for our understanding of politics in China today.

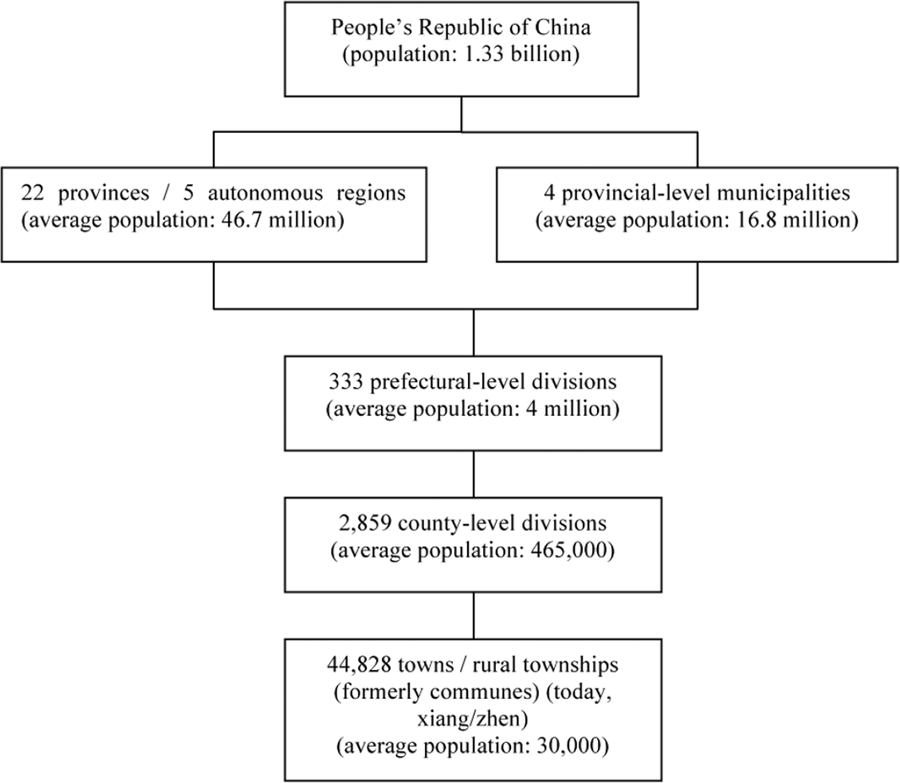

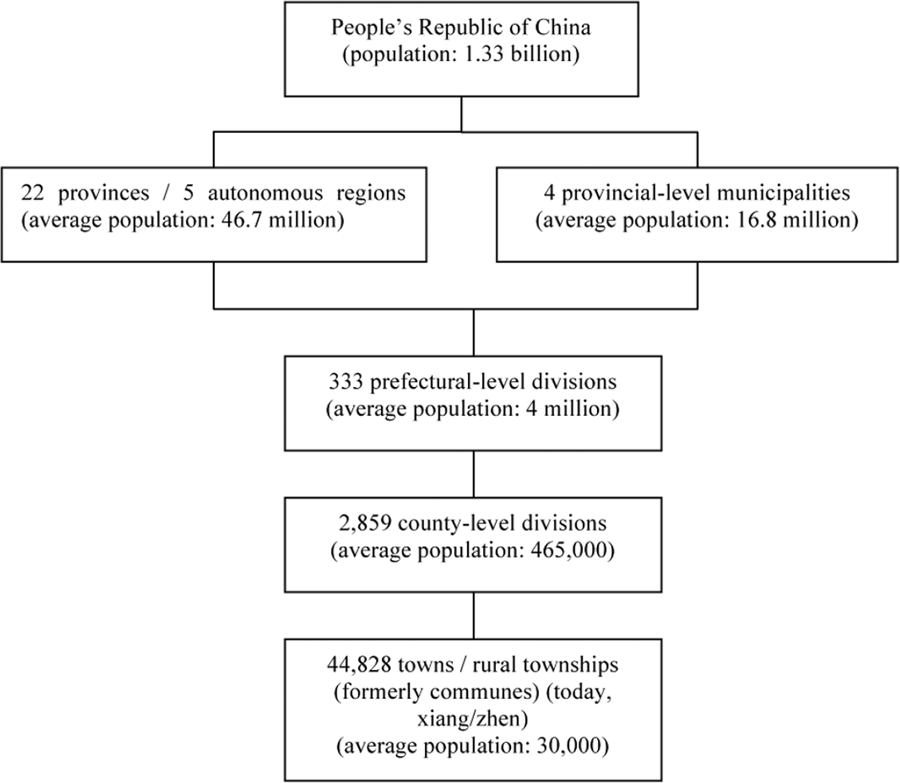

One of the ways scholars have attempted to better understand political developments in contemporary China has been to study patterns of governance at the grassroots. Studying Chinas local politics took on special importance following the collapse of totalitarian rule and the dismantling of the centrally planned economy in the late 1970s and early 1980s. As part of the administrative and economic reforms adopted during this period, local governments acquired much greater powers over their territories. The decisions made by local party and government leaders, particularly at sub-provincial levels, now have a much greater impact on Chinese society and economy than at any time since the founding of the Peoples Republic. Understanding what local governments do and why they do it has come to matter greatly for our broader understanding of how China is being governed in the twenty-first century.

During the first decade of post-Mao reforms county and township governments acquired so much clout that scholars began referring to them as local states.

Figure 1. Territorial Administration of the Peoples Republic of China. Figures are from 2011 data. Source: National Bureau of Statistics China, www.stats.gov.cn. Population figures do not include Hong Kong, Macao or Taiwan.

Another group of researchers saw parallels between the local state in China and the developmental states of East AsiaJapan, South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore. According to this scholarly perspective, the need to generate local tax revenue had driven Chinas local states to provide the infrastructure, conditions, and incentives needed for economic growth. Marc Blecher and Vivienne Shue, for example, made this claim for a rural county in Hebei Province.

Next page