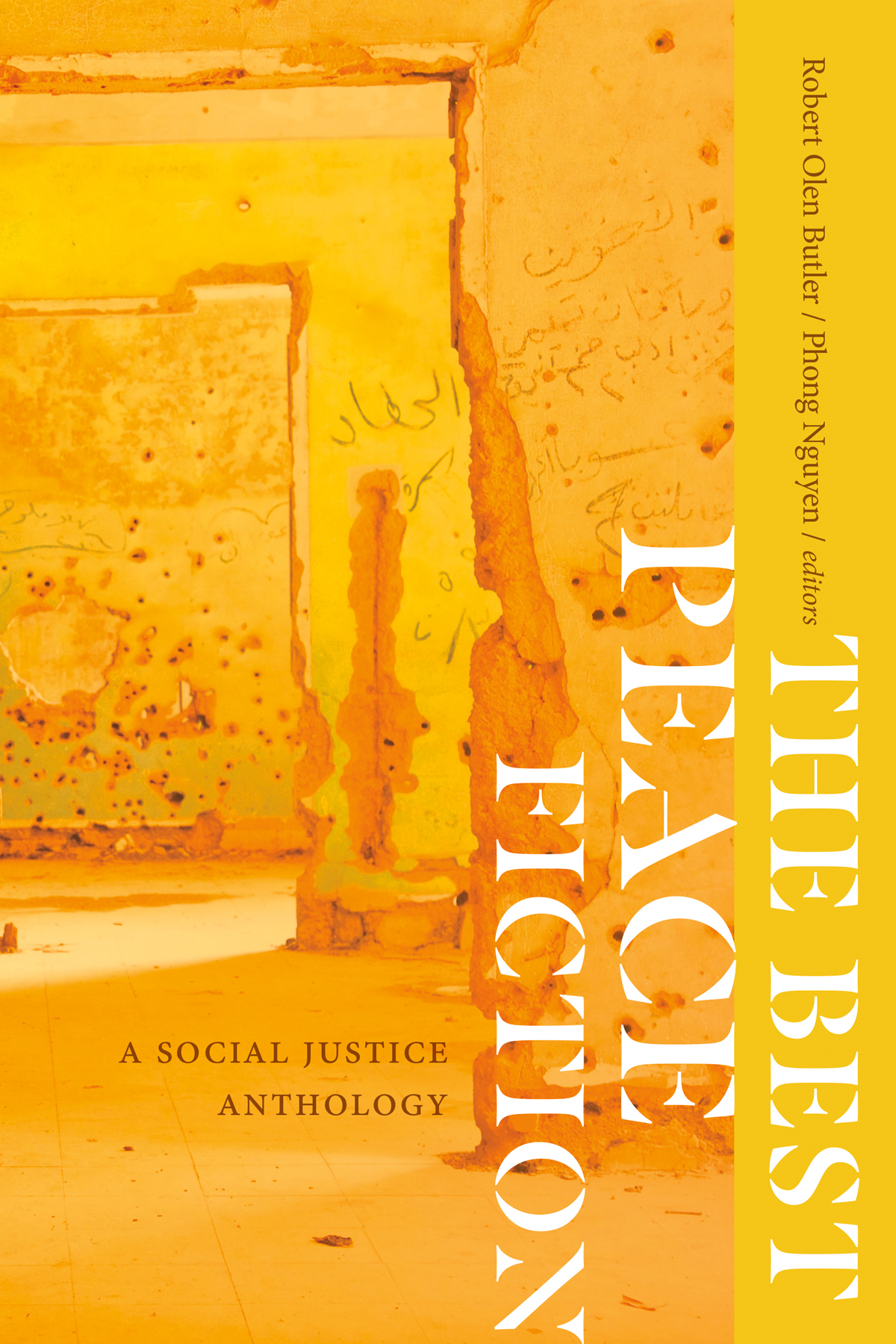

THE BEST PEACE FICTION

EDITED BY ROBERT OLEN BUTLER AND PHONG NGUYEN

THE BEST

PEACE

FICTION

A Social Justice Anthology

2021 by Phong Nguyen

All rights reserved. Published 2021

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN 978-0-8263-6303-9 (paper)

ISBN 978-0-8263-6304-6 (e-book)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021937825

Founded in 1889, the University of New Mexico sitson the traditional homelands of the Pueblo of Sandia. The original peoples of New MexicoPueblo, Navajo, and Apachesince time immemorial have deep connections to the land and have made significant contributions to the broader community statewide. We honor the land itself and those who remain stewards of this land throughout the generations and also acknowledge our committed relationship to Indigenous peoples. We gratefully recognize our history.

All the Names for God from All the Names They Used for God: Stories by Anjali Sachdeva, copyright 2018 by Anjali Sachdeva. Used by permission of Spiegel & Grau, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

All rights reserved.

Cover illustration Joel Carillet | istockphoto.com

Designed by Mindy Basinger Hill

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

In an interview with Alexander Weinstein for Pleiades: Literature in Context, George Saunders said that a story is an oomph-making machine, or its nothing at all. That measure for a storys successDoes it have the power to move the reader?is one that I adhere to as a writer and editor, and one that the selection team applied meticulously when narrowing down the submissions for our guest editor, Robert Olen Butler. But we needed to be moved in a particular way: toward empathy, toward awareness, and toward humanity. Especially the latter. In Creative Quest, Questlove wrote that effective creative endeavors demonstrate proof of life. At the core, we need to know that our art is not manufactured by, say, artificial intelligence, but that it is the actual product of one human appealing to another, whether directly or over a span of time and space.

It is no surprise that humans appealing to one another would tell stories, and it is no surprise that they would tell stories about war and strife. But what is fascinating and unexpected are the manifold stories we tell about the periphery of war, the aftermath of war, the war-raging-within-a-self-or-a-societythe unstable peace that we live in day to day, which we know to be built on a foundation of luck and privilege. Americans, in particular, have lived so long with the paradox of being outside the war zone themselves yet, as participants in a democracy, being complicit in war-making throughout the world, that we have become immune to its depiction. In screen media, violence is inherently aestheticized, and we live at a comfortable remove from the horrific events playing out before us. Therefore, we need a different approach in order to become aware of our peculiar place in the global scheme.

Peace is a slippery, sometimes oily, term. Like any vast abstraction, it can conjure up associations with soaring oratory, much of which is utilized to manipulate. It is particularly hollow in the mouths of politicians (of all alignments), priests (of all faiths), and gurus (of all persuasions). Yet there is no better word in the English language for all-that-is-not-war. In this anthology, peace fiction means stories that are close enough to the fire to singe but not catchdepicting those moments when war is on our minds or in our hearts, not inflicted upon our bodies. It means: not a war story or an antiwar story, but a story that reveals the ripples of war that move over the surface of all our lives.

This conception of peace fiction is not nave. It is not a utopian project. This anthology modestly poses whether literature has any role in furthering the ongoing pursuit of peace. If such a thing is possible, it requires the imaginative energies of creators to realize a future capable of great empathy. At its best, literature provides us with both the model and the means for achieving it. These fourteen stories are the most successful recent examples of such stories. Published in 2018 to 2019, they represent the current wave of fiction that looks outward and observes the world, rather than looking inward and repeating what weve already seen before.

We hope this anthology will be the first in a series of biennial anthologies that will have a different guest editor each time. Forty semifinalists were selected by me and interns at the University of Missouri, based on open submissions and the copious reading of published literary journals. These included individual journals with emphases in social justice and/or diversity, such as the Asian American issue of The Massachusetts Review, and the journal Obsidian, which is devoted entirely to works by authors of the African diaspora. These were then passed on to guest editor Robert Olen Butler, who selected fourteen stories for inclusion in the anthology.

We still have work to do to represent the true diversity of todays working writers. Future entries into the Best Peace Fiction anthology will prioritize and center our diverse population of authors, hopefully including works that highlight issues that came to the fore since 2020: the BLM movement, Indigenous rights, anti-Asian and anti-Muslim violence, and other issues that impact minoritized groups.

Literary journals are well represented in these pages: Kenyon Review has two stories in these pages. Ploughshares has four (!). The rest have appeared in Bellevue Literary Review, The Massachusetts Review, Iowa Review, The Missouri Review, Obsidian, London Magazine, or Witness. One story was selected from the story collection All the Names They Used for God by Anjali Sachdeva.

In Coffins for Kids! Wendy Rawlingss uses defamiliarization to reflect the absurdity of our twenty-first-century reality, where school shootings are a common, even weekly occurrence and where second-amendment activists rationalize the massacre of children by leveling blame at everyone but the firearms manufacturers. It approaches peace from the uneasy position of living in a violent society where war is an undeclared ethos.

All the Names for God by Anjali Sachdeva examines how the chaos of war swallows civilians and noncombatants and is inherently violent toward the innocent. The only peace to be achieved here is through the cathartic and fantastical exercise of dominance of will over the oppressor.

Down to the Levant by Joshua Idaszak conveys the texture of wartime in the periphery. Ada, After the Bomb by Alicia Upano looks at the periphery of war in the long viewthroughout the mid- to late-twentieth century. Miranda Golds A Small Dark Quiet explores the intricacies of grief and possibilities of hope in the aftermath of war. In Denis Wongs The Resurrection of Ma Jun, the plight of ethnic and religious minorities in China is depicted as a state of perpetual war. Camille F. Forbes reveals what a tautology war and peace can be for slaves on a plantation during the Civil War.

Dan Popes Bon Voyage, Charlie gets into how integrity can be compromised by the distortions of truth that war requires. In A Woman with a Torch, Mark Powell explores the psychic violence of our contemporary moment, despite the persistent illusion of peace; and whereas Lhomme bless by Ron Rash shows the ambiguous legacy of wars victors, The Man on the Beach by Josie Sigler Sibara examines the legacy and inheritance of wars losing side, of historys villains.