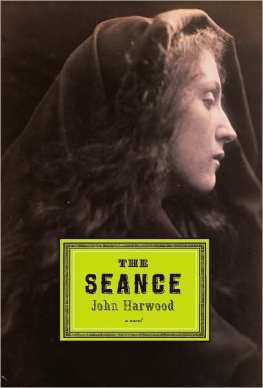

The Sance

John Harwood

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN HARCOURT

Boston New York

2009

ALSO BY JOHN HARWOOD

The Ghost Writer

First U.S. edition

Copyright 2008 by John Harwood

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to

Permissions Department, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company

6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, Florida 32887-6777.

[http://www.hmhbooks.com] www.hmhbooks.com

First published in 2008 by Jonathan Cape

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Harwood, John.

The sance/John Harwood.1st ed.

p. cm.

1. Haunted housesFiction. 2. MurderFiction.

3. ExtortionFiction. 4. EnglandFiction. I. Title.

PR9619.4.H37S43 2008

823'.92dc22 2007046029

ISBN 978-0-15-101203-9

Text set in Adobe Jenson / Designed by Cathy Riggs

Printed in the United States of America

MP 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Robin

TO MANIFEST A SPIRIT, TAKE TWENTY YARDS OF fine silk veiling, at least two yards wide and very gauzy. Wash carefully, and rinse seven times. Prepare a solution of one jar Balmain's Luminous Paint; half a pint of Demar Varnish, one pint odourless benzine and fifty drops lavender oil. Work thoroughly through the fabric while it is still damp, and then allow to dry for three days. Then wash with naphtha soap until all the odour is gone and the fabric is perfectly soft and pliable. In a darkened room, the fabric will appear as a soft, luminous vapour.

Revelations of a Spirit Medium (1891)

Part One

Constance Langton's Narrative

JANUARY 1889

If my sister Alma had lived, I should never have begun the sances. She died of scarlatina, soon after her second birthday, when I was five years old. I remember only fragments from the time before she died: Mama dancing Alma on her knee, and singing as she would never do again; reading my primer aloud to Mama while she rocked Alma's cradle with her foot; walking beside Annie, our nurse, while she pushed the perambulator past the Foundling Hospital with me holding on to the frame. I remember coming home after one of those walks and being allowed to nurse Alma by the drawing-room fire, feeling the heat of the flames on my cheek as I held her. I remember, toothough perhaps I was only told of itlying in a cot and shivering, looking up at a window which seemed very small and far away, and hearing the sound of weeping, muffled as if through thick cotton wool.

I do not know how long my own illness lasted, but it seems, in memory, as if I woke to find the house shrouded in darkness, and my mother changed beyond recognition. She kept to her room for many months, during which I was allowed only brief visits. The blinds were always drawn; often she seemed scarcely aware of my presence. And when at last she began to sit up, and then to emerge from her roomstooped like an old woman, her hair thin and lankshe remained sunk in lightless misery. Sometimes she would send for me, and then seem not to know why I had appeared, as if the wrong person had answered the summons. Whatever I ventured to say to her would be met with the same lifeless indifference, and if I sat in silence, I would feel the weight of her grief pressing upon me until I feared I would suffocate.

I wish I could say that my father grieved too; but if he did, I saw no sign of it. His manner with Mama was always polite and solicitous, very like that of Dr. Warburton, who would call from time to time and go away shaking his head. Papa was never ill, or cross, or out of sorts, and would no more have raised his voice than appear in public without waxing the points of his moustache. Sometimes in the mornings, after Annie had given me my bread and milk, I would creep downstairs and watch Papa and Mama through a crack in the dining-room door. "I trust you are feeling a little better today, my dear?" Papa would ask, and Mama would rouse herself wearily and say that yes, she supposed that she was, and then he would read The Times until it was time for him to set off for the British Museum, where he worked each day on his book. Most evenings he dined out; on Sundays, when the Museum was closed, he worked in his study. He did not go to church because he was busy with his work, and Mama could not go because she was not well enough, and so each Sunday Annie and I went to St. George's by ourselves.

Annie explained that Mama was grieving because God had taken Alma to Heaven, which I thought very cruel of Him; but then, if Alma was happy, and would never be ill again, and we would all be together again one day, why was Mama so dreadfully distressed? Because she loved Alma so dearly, Annie replied, and could not bear to be parted from her; but when the time of mourning was over, Mama would recover her spirits. In the meantime, all we could do was accompany Mama, once she was able to leave the house, to the only place she ever visited, the burial ground near the Foundling Hospital, and arrange fresh flowers on Alma's grave. I wondered why God had left Alma's body here, and taken only her spirit; and whether He was looking after Mama's spirits until she recovered them, but Annie declined to answer these questions, saying that I would understand when I was older.

She had dark brown hair, pulled back very tightly, and dark eyes, and a soft way of speaking; I thought her very pretty, though she insisted she was not. Annie had grown up in a village in Somerset, where her father was a stonemason, and had four brothers and three sisters; five more children had died when they were still very young. I had assumed, when she first told me this, that her mother must have been even more grief-stricken than mine. But no, said Annie, there had been no time for mourning; her mother had been far too busy looking after the rest of them. And no, they had not had a nurse; they had been far too poor for that. Things were much better now, though, because three of her brothers had gone for soldiers, and her two elder sisters were in service like herself, and they were all (except for one of the brothers, who had fallen into bad company) sending money home to their mother.

Whenever the weather was fine, Annie and I would go out for a walk in the afternoon. Our house was in Holborn, and on these walks we would sometimes pause at the Foundling Hospital to watch the foundling girls at play in their white pinafores and brown serge gowns. It looked as grand as a palace with its avenue of lamps, and more windows than you could count, and a statue of an angel before the entrance. The foundlings, Annie told me (she had a friend in service who had grown up here), had been brought here as infants by their mothers, who were too poor, or too ill to care for them. And yes, it was very sad for their mothers to have to give them up, but the foundlings had a much better life at the Hospital. The infants were all sent to good homes in the country until they were five or six years old, and then brought back to the Hospital for their schooling. They had meat for their dinner three days a week, and roast beef on Sundays, and when they were old enough, the boys would be sent for soldiers, and the girls for ladies' maids.

I wanted to know all about the mothers who had given their babies up for foundlings; after all, Annie's mother had been very poor, but she had kept them all at home. Annie seemed reluctant to answer, but eventually she told me that most of the foundlings were here because their fathers had run away and left their mothers alone.

"So if Papa were to run away," I asked, "would I be sent for a foundling?"

"Of course not, my child," said Annie, "your papa's not going to run away, and you've got me to look after you. And besides, you're too old for a foundling."