Contents

Guide

OTHER BOOKS BY KEITH MAILLARD

Two Strand River

Alex Driving South

The Knife in my Hands

Cutting Through

Motet

Light in the Company of Women

Dementia Americana (poetry)

Hazard Zones

Gloria

The Clarinet Polka

Running

Morgantown

Lyndon Johnson and the Majorettes

Looking Good

Twin Studies

Fatherless (memoir)

KEITH MAILLARD 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical including photocopying, recording, taping, or through the use of information storage and retrieval systems without prior written permission of the publisher or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright), One Yonge Street, Suite 800, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M5E 1E5.

Freehand Books acknowledges the financial support for its publishing program provided by the Canada Council for the Arts and the Alberta Media Fund, and by the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund.

Freehand Books

515 815 1st Street SW Calgary, Alberta T2P 1N3

www.freehand-books.com

Book orders: UTP Distribution

5201 Dufferin Street Toronto, Ontario M3H 5T8

Telephone: 1-800-565-9523 Fax: 1-800-221-9985

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

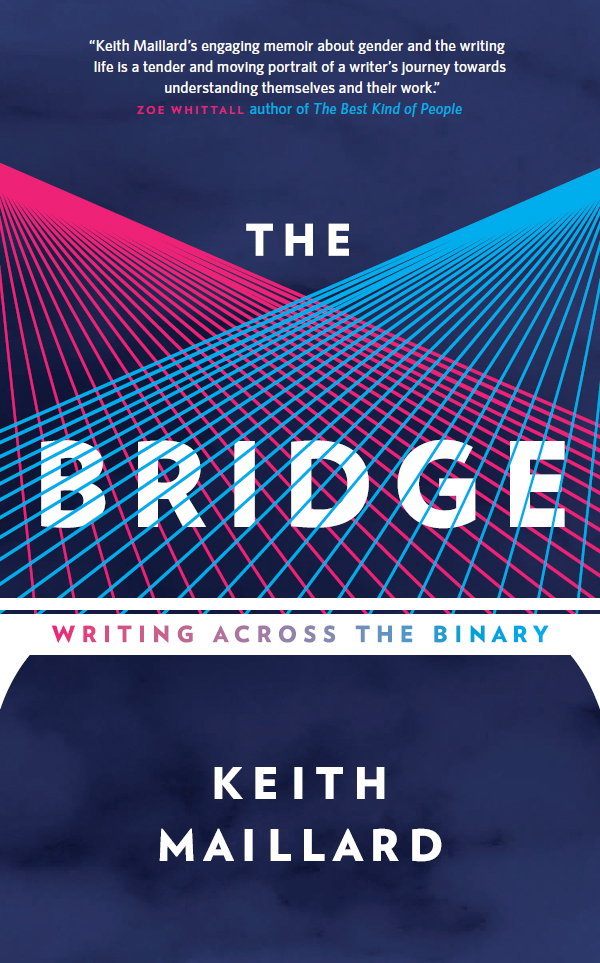

Title: The bridge : writing across the binary / Keith Maillard.

Names: Maillard, Keith, 1942 author.

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20200372181 | Canadiana (ebook) 2020037222X | ISBN 9781988298788 (softcover) | ISBN 9781988298795 (EPUB) | ISBN 9781988298801 (PDF)

Subjects: LCSH: Maillard, Keith, 1942 | LCSH: Gender-nonconforming people West Virginia Biography. | LCSH: Gender nonconformity. | CSH: Authors, Canadian (English) 20th century Biography. | LCGFT: Autobiographies.

Classification: LCC PS8576.A49 Z46 2021 | DDC C818/.5403dc23

Edited by Deborah Willis

Book design by Natalie Olsen, Kisscut Design

Cover photo 2Dew/Shutterstock.com

Author photo by Mary Maillard

Printed on FSC recycled paper and bound in Canada by Marquis

of The Movement include some writing that originally appeared in The Authors Afterward to Looking Good. Copyright 2006 by Keith Maillard from Looking Good. Reprinted with permission of Brindle & Glass, an imprint of TouchWood Editions.

for Mary

And in a world where femininity is so regularly dismissed, perhaps no form of gendered expression is considered more artificial and more suspect than male and transgender expressions of femininity. JULIA SERANO

There is nothing in human nature or the requirements of human social organization which intrinsically requires that a culture be contradictory, repressive and productive of violent and frustrated personalities. GARY SNYDER

If I cant describe who I am in this world I am who I am, whether or not I can describe it then I cant seek out others like me. ANDREA BENNETT

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

IN MARCH OF 1997 a lawyer in California called to tell me that my father had just died. I was deeply shaken. My parents had split up when I was about a year old, and I knew next to nothing about Gene Maillard, the man whod given me half my DNA. Except for a short bitter speech that she always repeated word for word, my mother had refused to talk about him. As an adult, Id made two attempts to find him, but I hadnt succeeded. He had died a wealthy man, a millionaire, and hed known who I was and where I was, but rather than reaching out to me, he had named me in his will so he could disinherit me. I was hurt and angry. My fathers executor, a kind man, sent me a few of my fathers personal items including two large scrapbooks in which he had documented his life. Okay, I thought, Gene might not have left me any of his money, but he had left me his story. I decided to write a book about him.

My fathers absence might have had a huge impact on my life, but if it did, I wasnt sure how. How do you write about something you didnt have? The light in our basement guest room is a murky half-light, and sounds are muffled. I went down there, stretched out flat on the bed with a blanket over me, and talked into a digital recorder. I knew that what I was trying to do was impossible to recover my childs mind but I wanted to see how close I could get. I said whatever came to me and did not censor anything. When I finished each day, I jacked the recorder into my computer and watched my speech-recognition software transform my spoken words into text. I thought Id do this for a day or two and that would be the end of it, but the memories kept coming for weeks. Much of what I was remembering had nothing to do with my father.

I gave the book I was writing a title, Fatherless, and I kept adding to it until it swelled up into a monstrosity a huge, complicated, incoherent, hairy, seven-headed beast, the despair of its author, over a thousand pages. Its difficult to see your writing clearly when youre tangled up in it, so I set that impossible manuscript aside and worked on other things. When I came back to it, I saw what the problem was. It wasnt one book; there were at least two books in there. I created a file called The Second Book, and anything that was not about my father I dumped into that file. I went through Fatherless a number of times, becoming more ruthless with every pass, until I was satisfied that I had stripped away every bit of excess. Eventually I had what I wanted a focused narrative that was the story of my search for Gene Maillard and an account of his life. Fatherless was published by West Virginia University Press in the fall of 2019.

For a long time I didnt bother to look into the second file. I knew roughly what was in there everything I had rejected but if there was actually another book, I didnt know what it was. Much of what I had dumped into that file was about me as a child. I had suffered from gender trouble to borrow Judith Butlers evocative term so I decided to focus on that, but when I began working my way through the file, I discovered that gender issues were so intertwined with the story of my beginnings as a writer that I couldnt separate those two strands. Okay, so the gender-troubled little boy who would grow up to be a writer that could be the heart of the matter and what if I cut everything else? It took a while. I stripped away extended evocations of our neighborhood just after the war, biographies of family pets, West Virginia tall tales, accounts of Ohio River floods, family legends going back five generations, portraits of aunts and uncles and cousins, a ghost story or two, a comprehensive catalogue of everything Id read up to the age of eighteen, and random musings about god knows what all stuff that might be of interest to my daughters or a future biographer but probably to no one else. What was left was the beginning of this book.

part I LIKE A GIRL

1

THE NOTION OF GENDER IDENTITY has been around since the 1950s and has largely been accepted by psychologists; it refers to the deep inner conviction we have about what gender we are. Most people know their gender identity by the time they are two or three. My memories dont go back quite that far, but as far back as I do remember, I was never certain. I asked my mother and grandmother over and over again, Am I a boy, or am I a girl? asked so many times they got sick of answering and started getting mad at me, and then I would hear, I