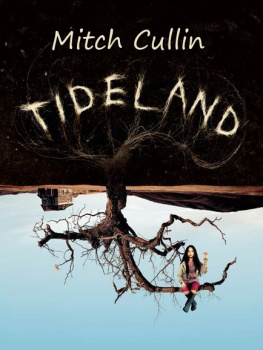

Cullin Mitch

The Post-War Dream

For my sister Charise Christian,

who taught me how to write my name and kept me reading

and for Howe Gelb,

surrogate big brother and my troubadour of choice

As when a man dreams, he reflects not that his body sleeps,

Else he would wake; so seem'd he entering his shadow.

William Blake,

Milton

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Portions of The Post-War Dream were first published under various titles in the following literary reviews: The Texas Review (Fall / Winter 2001) and Iron Horse Literary Review (First Frost 2002).With gratitude to those who offered support, research, advice, friendship, and inspiration: Coates Bateman, Howard Bloom, James Brady, Jeff Bridges, Joey Burns, Neko Case, the Christian family, John Convertino, my father Charles Cullin, Marianne Dissard, Nicole Dewey, Jane Dibblin, Luke Epplin, Norio Fukada, the entire Gelb clan, Terry and Amy Gilliam, Jemma Gomez, Tony Grisoni, Amon Haruta, Junko Kai, Patti Keating, Erika and Kainoa King, Steve and Jesiah King, M.A.G.O., Gabriella Martinelli, Tsutomu Nakayama, Frances Omori, the Parras, Joe Regal, my mother Charlotte Richardson, Charlotte Roybal, the God Hisao Shinagawa, Rennie and Brett Sparks, Special Agent Peter Steinberg, Nan Talese, Theodore Taylor, Brad Thompson, Carol Todd, Jeremy Thomas, Jonathan M. Weisgall, Sakae Yoshimoto and, of course, my comrade in every single thing under the sun: the most humble and kind Peter I. Chang.Lastly, two works of nonfiction proved invaluable to me during the writing of this novel, and I highly recommend both exhaustively researched and informative books: The Bridge at No Gun Ri, by Charles J. Hanley, Sang-Hun Choe, and Martha Mendoza (Owl Books); and Ovarian Cancer: Your Guide to Taking Control, by Kristine Conner and Lauren Langford (O'Reilly Patient-Centered Guides), a book which provided needed information during my late mother's struggle with ovarian cancer.

Throughout the years Hollis has observed them among his dreams, watching from a distance as they foraged under a blackened sky. After a time he understood that they, like him, had sensed the flux of earth, yet were undaunted: having journeyed perhaps twenty miles in almost fifty days, a procession of cows nomadic Herefords and Jerseys grazed onward, wobbling over a moonlit prairie, bulky heads lowered; their hooves crunched sandstone and pumice, and their excreta, hardening behind them, marked the slender trail in uneven circles testaments to how far they had come, symbols of presence, like the burned-out and rusting wheelless cars they encountered within unkempt pastures of bluebonnets and high brittle grass, or the gutted houses abandoned on good soil (porches collapsing, doors gone, the wind sneaking through busted panes into dim interiors), or any number of fading signposts passed along the way, those many things fashioned by man-made design and then left again and again as the herd proceeded, weaving blindly ahead for no other reason than it must.

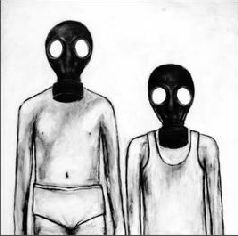

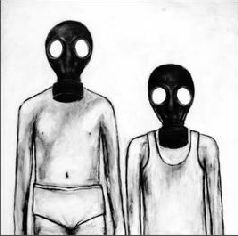

And there, too, he has infrequently witnessed the approach of other languid creatures: half-naked human figures emerging whenever the recurring cows failed to manifest, hundreds of pale bodies cutting through the landscape, angling across the same nighttime terrain but traveling in the opposite direction. That serpentine formation of listless souls wound back into the darkness the shapes of children, men and women, mothers cradling infants, the elderly coming from where the cows had been headed, drawing nearer while never quite reaching him. But it was the gas mask each one wore which disturbed him the most such cumbersome equipment obscuring their faces, too large for the heads of small children and practically consuming the entire bodies of the infants, giving the group a uniform, superficial appearance not unlike that of cattle. Even so, he perceived their determined movements as a kind of miserable retreat, a retrogression toward the past and, indeed, toward the living where, upon arriving at their destination, he imagined the masks would be cast aside and all of them would inhale freely once more.

Yet every step of their bare feet was now preceded by labored breath, a collective exhalation delivered in unison and released as a muted, staccato gasp through chemical air filters while their paper-thin skin contracted around pronounced rib cages, and many of their arms hung like broken branches at their sides. As the ragged column advanced steadily in the moonlight, he realized the physical condition of the people had deteriorated badly since he'd first seen them decades ago. Their clothing was either reduced to shreds or had fallen away, their ankles and feet were covered with sores, their hair was so long that it ran the length of their backsides, and the men's thick beards jutted from beneath their masks. In that stream of pale, dirty bodies only their protruding bones shone clearly as they marched one after the other.

Where are you going? he had once asked them without speaking. What is it you're looking for? What do you want?

Later on, after having grown accustomed to their rare visitations, he offered the men cigarettes, the women Dixie cups filled with apple juice, the children Halloween candy from an orange plastic pumpkin (Please, you must be hungry here, have something to drink have some juice please, help yourself please ), but his gestures went unacknowledged, his voice remained unheard. They, as usual, strayed well beyond his grasp, moving resolutely on the trail, somehow receding even while approaching.

However fast he walked, Hollis was never able to catch up with them. For years he tried without any success, his life evolving from youth to retirement while the processions continued to elude him. But as was always the case, those irregular dreams dissolved with his sudden waking, and he opened his eyes in bedrooms steeped by shadows his body shuddering as if it had retained something unwholesome from the land of his visions and carried it then into the imperturbable, calm world he has made for himself.

Now in the waning months of the twentieth century, snow fell last evening without warning, drifting from above as if the heavens had been wrung in the hands of God, spilling down upon an unsuspecting desert, covering all which lay exposed below the dark-gray clouds. Waking well after mid-night an open hardback of Tom Clancy's Rainbow Six resting against his chin, a coffee cup half filled with Glenfiddich sitting nearby on the floor Hollis was comfortable inside his house, stretched across the living-room couch and kept snug by a beige terry-cloth bathrobe. Lifting the novel, he began reading where he had left off, although his attention wasn't really held by the writing; his eyes scanned paragraphs, failing to absorb sentences, until, at last, he set the book aside, turning his gaze elsewhere as the Glenfiddich was absently retrieved, the liquor seeping warmly past his lips. On the other side of the living room the front curtains were drawn, revealing the picture window and what existed just beyond it: a torrent of snowflakes wavering to the earth, some pattering at the glass like moths before dissolving into clear drops of moisture. Presently, he was standing there in his bathrobe, resting a palm against the window, sensing the cold while buffered by efficient central heating. There, also, he caught a glimpse of himself as an obscure, diaphanous man reflected on the glass; his transposed image was cast amongst the wide residential street the adjacent and similarly designed homes, the xeriscaped lawns backlit by a table lamp but also illumed in that frozen vapor which brightened the night, that curious downpouring which smothered the gravel-laden property and changed his Suburban Half-Ton LS from sandalwood metallic to an almost solid white. He realized, then, that the outside cold had somehow managed to bypass the insulated flesh and blood of his left leg needling into the marrow of his once torn-apart thigh, reviving the ancient injury caused by a North Korean's bullet that had ripped into his leg, striking him while his M1 returned fire; the throbbing, indefinite pain had been felt by him since, but only in the bleakest of winter months, sometimes giving him a slight limp as if to summon his previous incarnation: a young private in the U.S. Army, a rifleman at the outset of a half-forgotten war.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS