The

Complete

Short Stories of

Ernest Hemingway

The Finca Viga edition

WHEN PAPA AND MARTY FIRST RENTED in 1940 the Finca Viga which was to be his home for the next twenty-two years until his death, there was still a real country on the south side. This country no longer exists. It was not done in by middle-class real estate developers like Chekhovs cherry orchard, which might have been its fate in Puerto Rico or Cuba without the Castro revolution, but by the startling growth of the population of poor people and their shack housing which is such a feature of all the Greater Antilles, no matter what their political persuasion.

As children in the very early morning lying awake in bed in our own little house that Marty had fixed up for us, we used to listen for the whistling call of the bobwhites in that country to the south.

It was a country covered in manigua thicket and in the tall flamboyante trees that grew along the watercourse that ran through it, wild guinea fowl used to come and roost in the evening. They would be calling to each other, keeping in touch with each other in the thicket, as they walked and scratched and with little bursts of running moved back toward their roosting trees at the end of their days foraging in the thicket.

Manigua thicket is a scrub acacia thornbush from Africa, the first seeds of which the Creoles say came to the island between the toes of the black slaves. The guinea fowl were from Africa too. They never really became as tame as the other barnyard fowl the Spanish settlers brought with them and some escaped and throve in the monsoon tropical climate, just as Papa told us some of the black slaves had escaped from the shipwreck of slave ships on the coast of South America, enough of them together with their culture and language intact so that they were able to live together in the wilderness down to the present day just as they had lived in Africa.

Viga in Spanish means a lookout or a prospect. The farmhouse is built on a hill that commands an unobstructed view of Havana and the coastal plain to the north. There is nothing African or even continental about this view to the north. It is a Creole island view of the sort made familiar by the tropical watercolors of Winslow Homer, with royal palms, blue sky, and the small, white cumulus clouds that continuously change in shape and size at the top of the shallow northeast trade wind, the brisa.

In the late summer, when the doldrums, following the sun, move north, there are often, as the heat builds in the afternoons, spectacular thunderstorms that relieve for a while the humid heat, chubascos that form inland to the south and move northward out to the sea.

In some summers, a hurricane or two would cut swaths through the shack houses of the poor on the island. Hurricane victims, damnificados del cicln, would then add a new tension to local politics, already taut enough under the strain of insufficient municipal water supplies, perceived outrages to national honor like the luridly reported urination on the monument to Jos Marti by drunken American servicemen and, always, the price of sugar.

Lightning must still strike the house many times each summer, and when we were children there no one would use the telephone during a thunderstorm after the time Papa was hurled to the floor in the middle of a call, himself and the whole room glowing in the blue light of Saint Elmos fire.

During the early years at the finca, Papa did not appear to write any fiction at all. He wrote many letters, of course, and in one of them he says that it is his turn to rest. Let the world get on with the mess it had gotten itself into.

Marty was the one who seemed to write and to have kept her taste for the high excitement of their life together in Madrid during the last period of the Spanish Civil War. Papa and she played a lot of tennis with each other on the clay court down by the swimming pool and there were often tennis parties with their friends among the Basque professional jai alai players from the fronton in Havana. One of these was what the young girls today would call a hunk, and Marty flirted with him a little and Papa spoke of his rival, whom he would now and again beat at tennis by the lowest form of cunning expressed in spins and chops and lobs against the towering but uncontrolled honest strength of the rival.

It was all great fun for us, the deep-sea fishing on the Pilar that Gregorio Fuentes, the mate, kept always ready for use in the little fishing harbor of Cojimar, the live pigeon shooting at the Club de Cazadores del Cerro, the trips into Havana for drinks at the Floridita and to buy The Illustrated London News with its detailed drawings of the war so far away in Europe.

Papa, who was always very good at that sort of thing, suggested a quotation from Turgenev to Marty: The heart of another is a dark forest, and she used part of it for the title of a work of fiction she had just completed at the time.

Although the Finca Viga collection contains all the stories that appeared in the first comprehensive collection of Papas short stories published in 1938, those stories are now well known. Much of this collections interest to the reader will no doubt be in the stories that were written or only came to light after he came to live at the Finca Viga.

JOHN, PATRICK, AND GREGORY HEMINGWAY 1987

THERE HAS LONG BEEN A NEED FOR A complete and up-to-date edition of the short stories of Ernest Hemingway. Until now the only such volume was the omnibus collection of the first forty-nine stories published in 1938 together with Hemingways play The Fifth Column. That was a fertile period of Hemingways writing and a number of stories based on his experiences in Cuba and Spain were appearing in magazines, but too late to have been included in The First Forty-nine.

In 1939 Hemingway was already considering a new collection of stories that would take its place beside the earlier books In Our Time, Men Without Women, and Winner Take Nothing. On February 7 he wrote from his home in Key West to his editor Maxwell Perkins at Scribners suggesting such a book. At that time he had already completed five stories: The Denunciation, The Butterfly and the Tank, Night Before Battle, Nobody Ever Dies, and Landscape with Figures, which is published here for the first time. A sixth story, Under the Ridge, would appear shortly in the March 1939 edition of Cosmopolitan.

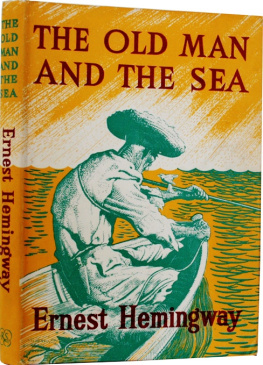

As it turned out, Hemingways plans for that new book did not pan out. He had committed himself to writing three very long stories to round out the collection (two dealing with battles in the Spanish Civil War and one about the Cuban fisherman who fought a swordfish for four days and four nights only to lose it to sharks). But once Hemingway got underway on his novellater published as For Whom the Bell Tollsall other writing projects were laid aside. We can only speculate on the two war stories he abandoned, but it is probable that much of what they might have included found its way into the novel. As for the story of the Cuban fisherman, he did eventually return to it thirteen years later when he developed and transformed it into his famous novella, The Old Man and the Sea.

Many of Hemingways early stories are set in northern Michigan, where his family owned a cottage on Waloon Lake and where he spent his summers as a boy and youth. The group of friends he made there, including the Indians who lived nearby, are doubtless represented in various stories, and some of the episodes are probably based at least partly on fact. Hemingways aim was to convey vividly and exactly moments of exquisite importance and poignancy, experiences that might appropriately be described as epiphanies. The posthumously published Summer People and the fragment called The Last Good Country stem from this period.