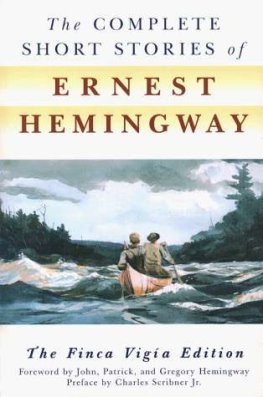

Scribner

An Imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright renewal 1989 by Lillian Ross

Originally published in 1961 in The New Yorker.

Excerpt from Workouts previously published in 1986 in The New Yorker.

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Scribner Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

First Scribner ebook edition July 2015

SCRIBNER and design are registered trademarks of The Gale Group, Inc. used under license by Simon & Schuster, Inc., the publisher of this work.

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

ISBN 978-1-5011-2603-1 (ebook)

P REFACE

I first met Ernest Hemingway on the day before Christmas in 1947, in Ketchum, Idaho. I was on my way back to New York from Mexico, where I had gone to see Sidney Franklin, the American bullfighter from Brooklyn, about whom I was trying to write my first Profile for The New Yorker. Hemingway had known Franklin as a bullfighter in Spain in the late twenties and early thirties. I had gone to some corridas in Mexico with Franklin, and had been appalled and scared to death when I got my first look at what goes on in a bull ring. Although I appreciated the matadors cape work with the bulls, and the colorful, ceremonial atmosphere, I wasnt fond of bullfighting as such. I guess what interested me was just how Franklin, son of a hard-working policeman in Flatbush, had become a bullfighter. When Franklin told me that Hemingway was the first American who had ever spoken to him intelligently about bullfighting, I telephoned Hemingway in Ketchum. Hemingway liked spending vacations there, skiing and hunting, away from his home in San Francisco de Paula, near Havana, Cuba, and later on he bought a house in Ketchum. When I called, Hemingway was staying in a tourist cabin with his wife, Mary, his sonsJohn, Patrick, and Gregoryand some fishing friends from Cuba, and he hospitably invited me to drop in and see him on my way back East.

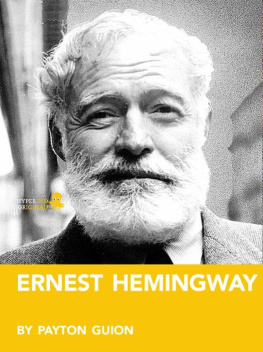

The first time I saw Hemingway was about seven oclock in the morning, in front of his tourist cabin, shortly after my train got in. He was standing on hard-packed snow, in dry cold of ten degrees below zero, wearing bedroom slippers, no socks, Western trousers with an Indian belt that had a silver buckle, and a lightweight Western-style sports shirt open at the collar and with button-down pockets. He had a graying mustache but had not yet started to wear the patriarchal-looking beard that was eventually to give him an air of saintliness and innocencean air that somehow or other never seemed to be at odds with his ruggedness. That morning, he looked rugged and burly and eager and friendly and kind. I was wearing a heavy coat, but I was absolutely freezing in the cold. However, Hemingway, when I asked him, said he wasnt a bit cold. He seemed to have tremendous built-in warmth. I spent a wonderful day of talk and Christmas shopping with the Hemingways and their friends. Mary Hemingway, like her husband, was warm and gracious and knowledgeable, as well as capable of brilliantly filling the difficult role of famous writers wife. She enjoyed the same things he did, and seemed to me to be the perfect partner for him.

Shortly after my Ketchum visit, Hemingway wrote to me from Cuba that he thought I was the person least suited in the world to do an article on bullfighting. Nevertheless, I went ahead, and eventually did finish the Profile of Franklin. After the magazines editors had accepted it, I sent Hemingway some queries about it, and he replied most helpfully in a letter winding up with the statement that he looked forward with horror to reading it. In the meantime, though, The New Yorker published a couple of shorter pieces of mine, and Hemingway and his wife, both regular readers of the magazine (he once wrote me that my mob was his mob, too), seemed to like them. When the Franklin Profile was published, I had a letter from Hemingway, scrawled in pencil, from Villa Aprile, Cortina dAmpezzo, Italy, in which he said that what he called the Sidney pieces were fine. In his crowded life, he did his best to remember exactly what he had said to you before, and he made a point, generously, of correcting himself when he felt that it was necessary. His compliments were straight and honest, and they were designed to make people feel good. He might call you reliable and compare you to Joe Page and Hugh Casey, and you wouldnt have to be an archivist of baseball to realize you were being praised. The way he wrote in his letters, the way he talked, in itself made me feel goodit was so fresh and wonderful. He was generous in his conversation. He didnt hoard his ideas or his thoughts or his humor of his opinions. He was so inventive that he probably had the feeling there was plenty more where that came from. But whatever his feeling might have been, he would have talked as he did out of sheer generosity. He offered so much in what he said, and always with fun and with sharp understanding and compassion and sensitivity. When he talked, he was free. The sound and the content were marvellously alive.

In the spring of 1950, I wrote a Profile of Hemingway for The New Yorker. It was a sympathetic piece, covering two days Hemingway spent in New York, in which I tried to describe as precisely as possible how Hemingway, who had the nerve to be like nobody else on earth, looked and sounded when he was in action, talking, between work periodsto give a picture of the man as he was, in his uniqueness and with his vitality and his enormous spirit of fun intact. Before it was published, I sent a galley proof of it to the Hemingways, and they returned it marked with corrections. In an accompanying letter, Hemingway said that he had found the Profile funny and good, and that he had suggested only one deletion. Then a strange and mysterious thing happened. Nothing like it had ever happened before in my writing experience, or has happened since. To the complete surprise of Hemingway and the editors of The New Yorker and myself, it turned out, when the Profile appeared, that what I had written was extremely controversial. Most readers took the piece for just what it was, and I trust that they enjoyed it in an uncomplicated fashion. However, a certain number of readers reacted violently, and in a very complicated fashion. Among these were people who objected strongly to Hemingways personality, assumed I did the same, and admired the piece for the wrong reasons; that is, they thought that in describing that personality accurately I was ridiculing or attacking it. Other people simply didnt like the way Hemingway talked (they even objected to the playful way he sometimes dropped his articles and spoke a kind of joke Indian language); they didnt like his freedom; they didnt like his not taking himself seriously; they didnt like his wasting his time on going to boxing matches, going to the zoo, talking to friends, going fishing, enjoying people, celebrating his approach to the finish of a book by splurging on caviar and champagne; they didnt like this and they didnt like that. In fact, they didnt like Hemingway to be Hemingway. They wanted him to be somebody elseprobably themselves. So they came to the conclusion that either Hemingway had not been portrayed as he was or, if he was that way, I shouldnt have written about him at all. Either they had dreary, small-minded preconceptions about how a great writer should behave and preferred their preconceptions to the facts or they attributed to me their own pious disapproval of Hemingway and then berated me for it. Some of the more devastation-minded among them called the Profile devastating. When Hemingway heard about all this, he wrote to reassure me. On June 16, 1950, he wrote that I shouldnt worry about the piece and that it was just that people got things all mixed up. A number of times he wrote about the attitude of people he called the devastate people. Some people, he said, couldnt understand his enjoying himself and his not being really spooky; they couldnt understand his being a serious writer without being pompous.

Next page