Contents

Guide

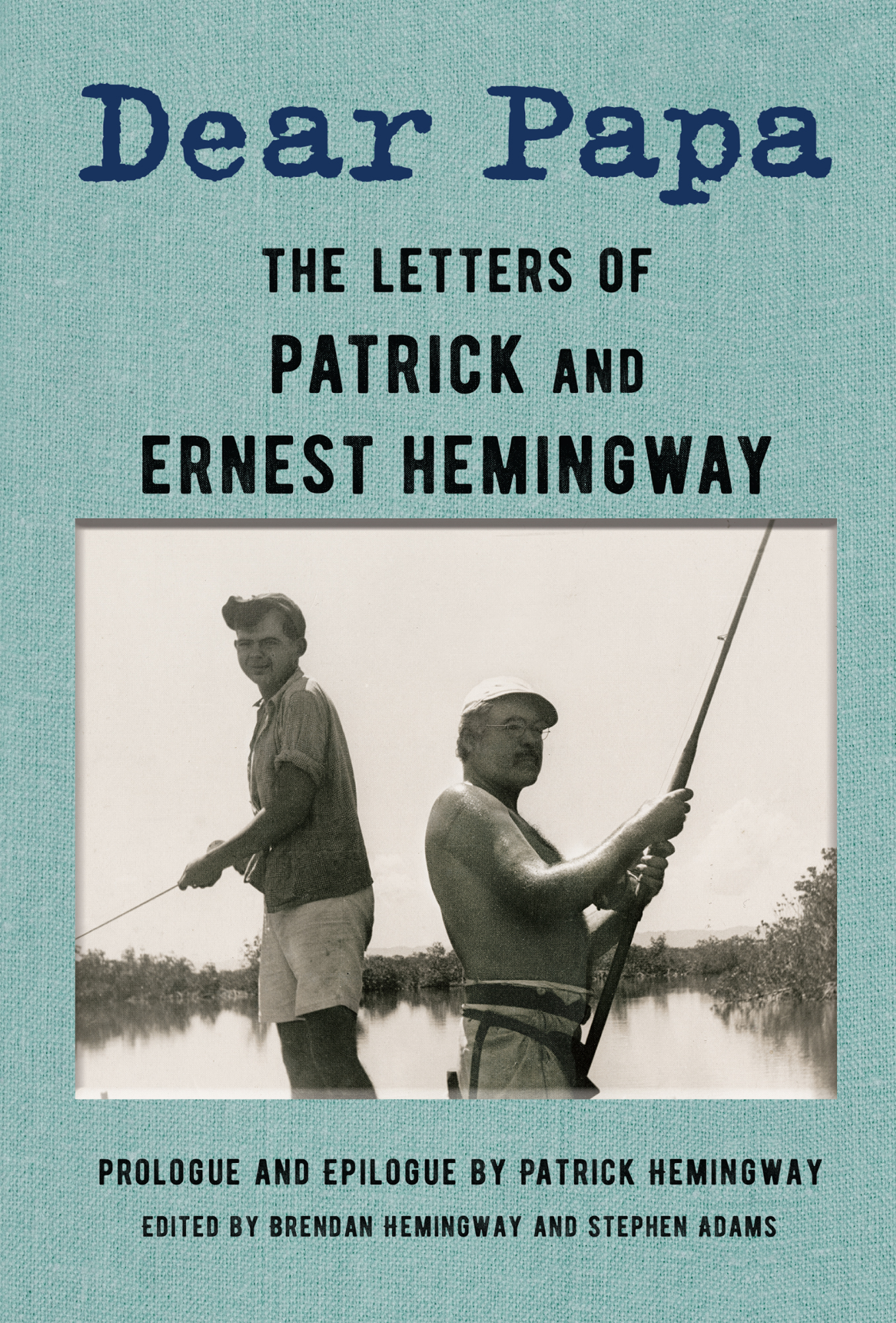

Dear Papa

The Letters of Patrick and Ernest Hemingway

Prologue and Epilogue by Patrick Hemingway

Edited by Brendan Hemingway and Stephen Adams

PROLOGUE

THIS BOOK contains selected conversations, by letter, between a father and son. It is an attempt to answer the question I have been often asked, by friends and strangers alike: Did I know my father?

There is a lot of hunting and fishing in these letters, but I think the significance of this correspondence is not the hunting and fishing. Its the light it casts on our relationship, and how I grew to know my father. I grew to know him as a person, quite different than how he is often portrayed. The man I knew tried very hard to be a good family man. I think our correspondence shows he was intimately connected with his wives and his children all his life.

I would like to call up a letter by my father that he wrote to F. Scott Fitzgerald in 1925, when Papa had only one family and marriage to play with.

July 1, 1925

Burguete, Navarra

Dear Scott,

We are going in to Pamplona tomorrow. Been trout fishing here. How are you? And how is Zelda?

I am feeling better than Ive ever felt havent drunk any thing but wine since I left Paris. God it has been wonderful country. But you hate country. All right omit description of country. I wonder what your idea of heaven would be. A beautiful vacuum filled with wealthy monogamists, all powerful and members of the best families all drinking themselves to death. And hell would probably be an ugly vacuum full of poor polygamists unable to obtain booze or with chronic stomach disorders that they called secret sorrows.

To me a heaven would be a big bull ring with me holding two barrera seats and a trout stream outside that no one else was allowed to fish in and two lovely houses in the town; one where I would have my wife and children and be monogamous and love them truly and well and the other where I would have my nine beautiful mistresses on 9 different floors and one house would be fitted up with special copies of the Dial printed on soft tissue and kept in the toilets on every floor and in the other house we would use the American Mercury and the New Republic. Then there would be a fine church like in Pamplona where I could go and be confessed on the way from one house to the other and I would get on my horse and ride out with my son to my bull ranch named Hacienda Hadley and toss coins to all my illegitimate children that lined the road. I would write out at the Hacienda and send my son in to lock the chastity belts onto my mistresses because someone had just galloped up with the news that a notorious monogamist named Fitzgerald had been seen riding toward the town at the head of a company of strolling drinkers.

Well anyway were going into town tomorrow early in the morning. Write me at the

Hotel Quintana

Pamplona

Spain

Or dont you like to write letters. I do because its such a swell way to keep from working and yet feel youve done something.

So long and love to Zelda from us both.

Yours,

Ernest

This letter demonstrates Ernests complex personality and his ability to create art with his writing. As my maturity developed, I too could use my letters to create something similar to his and in certain fields, such as poetry and hunting, I could openly compete. This letter to Fitzgerald was written three years before I was born and John Hadley Nicanor Hemingway was Papas only son and child. My appearance on the scene, the son of Pauline Pfeiffer Hemingway, altered the complexity of the family Papa had to deal with. This complexity also affected the development of the letters between Papa and me. In the first place, there was the matter of the Catholic Church. Papa had entered into a relationship with the Catholic Church during the war that was fought in Italy, a strongly Catholic country. With his second marriage to Pauline, he would become very much under the influence of her religion, and I would be brought up as a Catholic child. This relationship in turn would be affected by Papa and Paulines divorce in order for him to marry Martha Gellhorn. These changes that Papa had to make in the families he felt responsible for, very much underlie the trajectory of our correspondence and the task of getting to know my father.

Patrick Hemingway

INTRODUCTION

DEAR PAPA is a look into the intimate relationship between Ernest Hemingway and his middle son, Patrick. It is an abridged collection of the correspondence that they maintained throughout their lives together.

Patrick Hemingway started the Dear Papa project in 2020 when he enlisted the help of both his nephew, Brendan Hemingway, and his grandson, Stephen Adams. Patricks intention was to use the large archive of this material to show the world what his parent was like as a father.

The world already knows Ernest Hemingway the writer and Papa Hemingway the larger-than-life celebrity. Now Patrick wants the world to know the devoted family man and engaged father by sharing selected letters over their entire collective life together.

Ernest Hemingway was married four times and had three children between two of his four wives, so the supporting cast in these letters is large. He married Hadley Richardson in 1921, and they divorced in 1927. Hadley was the mother of Patricks beloved older brother, Jack, but she would not play much of a role in Patricks life. Patrick and his brother Gregorys mother, Pauline Pfeiffer, was married to Hemingway 19271940. She was a constant in Patricks life until her untimely death in 1951, when Patrick was twenty-three years old. Martha Marty Gellhorn married Hemingway in 1940, and they divorced in 1945. Martha was especially fond of Patrick, and the two remained in contact for the rest of Marthas life. And in 1946, Hemingway married Mary Welsh, who was widowed by his death in 1961. Although Patrick was nearly eighteen years old when Mary married Ernest, they developed a cordial relationship and shared a keen interest in art history.

As Ernests middle son, Patrick was the stereotypically dutiful peacemaking middle child who kept in touch with his father until his fathers death. They corresponded through thick and thin, always making it through rough patches in their relationship in a way that was not typical for Ernest, who tended to withdraw from confrontation and retreat from high emotion.

In addition to the large cast of characters, many of these characters are referred to by nicknames. The Hemingway family have long had a tradition of nicknames, and Ernest was particularly good at it and into it.

Another family tradition you will observe in the letters is the toosie, which is a way to represent a kiss: a circle with a dot in it, which we usually typeset as (.). Ernest inherited this tradition and passed it on.

Neither father nor son was much for spelling, so many errors have been fixed to avoid interfering with the reading experience.

When we say letters, we mean all the correspondence, which included not only letters but telegrams, postcards, and short notes.

As we reviewed the letters in 2020, they were between eighty-eight years old and fifty-nine years old. Language and stereotyping that was commonplace then is recognized as harmful now. Patrick was adamant that there was to be no whitewashing, so none of the problematic words or phrases he or his father used in their letters have been left out. No excuses will be made. There are also graphic depictions of hunting and fishing that some readers may find unsavory. Our goal is historical accuracy. We apologize in advance to anyone who is put off by the raw nature of this text.