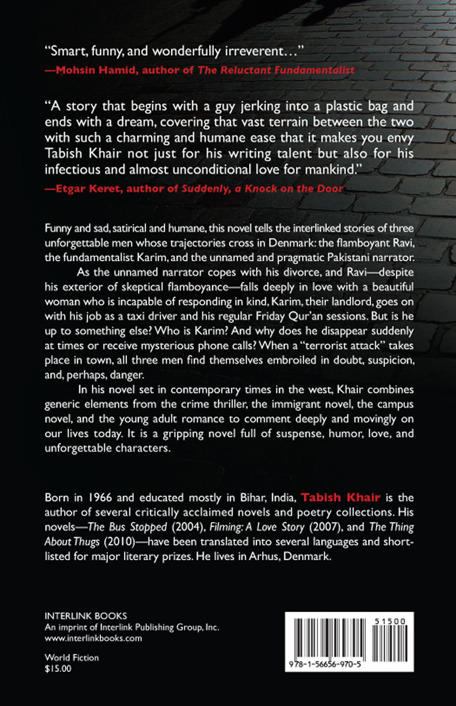

Tabish Khair

HOW TO FIGHT ISLAMIST TERROR FROM THE MISSIONARY POSITION

With thanks to Sam Selvon and Dany Laferrire

Always begin in medias res, said the only girl I ever fucked who had an MFA in writing (from an American university). At the moment she gave me that bit of advice about writing, we were almost in the middle of something else and consequently the rest of her advice was cut short or has since slipped my memory.

Having set myself the task of providing a full account of the events that have exercised considerable media attention in Denmark in recent months and that involved me, though not mentioned by name, I now wish that I had paid more attention to her words and less attention to her. This, however, was difficult.

But whatever she or her MFA professors might have said, I am certain that this account starts one winter morning on Kastelsvej, which is a desolate suburban street off the main road leading from rhus to Randers, where I sat behind the steering wheel of a parked Hyundai i10, engine running for warmth, and tried desperately to jerk off into a plastic container with a label bearing the name and social security number of my wife. This was a little over two years ago.

I had ten minutes to fill the container to the best of my capacity and drive it to the fertility clinic, which was just around the corner and would be opening at seven, in exactly ten minutes. Then I had an hour to drive to a high school in Randers, a forty-five-minute drive in light traffic, where I was supposed to deliver a guest lecture at eight. Hence the desperation.

The fact that these plastic containers are made by someone with a rather optimistic idea of the productive capacity of man did not help. The fact that I had been following this routine for more than six months did not help. And the fact that a patrol car was slowly cruising the main road in the morning haze did not help at all.

I prayed to the God I did not believe in that the patrol car would cruise on and not turn into a desolate side street with a Hyundai i10 parked in it, its engine running. Even as I duly submitted my prayer in triplicate, I knew it stood no chance. It was bound to be rejected. No self-respecting patrol car could ignore such a target of investigation so early in the morning. Doing my best with one hand to keep to my schedule, I observed the car in my rearview mirror. It slowed down. Then its left indicator winked hazily and its headlights cut through the fog into my street.

My heart sank. If this particular cop found the sight of a law-abiding Japanese or Far Asian car suspicious, parked no matter where and how, what would he think when he discovered that the driver of the car was a more or less Muslim-skinned man? The excitement of the situation must have helped, for at that very moment my beleaguered appendage sent an SOS of sensation back to me, a silent version of the whistle that old-fashioned trains let off in old-fashioned films before they start pulling out of old-fashioned stations. Did I have the time to let this train pull out and cap the evidence before the patrol car pulled up? And if I did, would I be able to get my clarifications in place quickly enough to make it to the clinic and then to my lecture, for which I was going to be paid money that my gaily mortgaging bank could use in these times of financial crisis?

I had to make a quick decision. And suddenly, after months of indecision, I knew what I had to do. I looked at the name on that ambitious plastic container. I said, in my heart or perhaps even audibly, I am sorry. I might even have said: no more. I zipped up. Then I slowly pressed the clutch, changed the gear, waved nonchalantly at the cops in the patrol car, and drove back home.

If I had not said sorry at that moment and definitely if I had not said no more later on, I would not have gotten divorced. And if I had not gotten divorced, I would not have started sharing a flat with Karim and Ravi. And if I had not started sharing a flat with Karim and Ravi, the account that I am going to give youwhich is a more complex version of what you might have read in the paperswould not have been necessary.

So in medias res or coitus interruptus or whatever else in Latin Ravi might suggest, this is where it all started.

I had known Ravi for three years, ever since I moved to rhus with my English wife. This was when, having completed a PhD at Surrey, I was offered my first full-time position, with the carrot of tenure tied to its stick of pedagogic overwork. Following my divorce, with my wife heading back to Guildford in Surrey, Ravi and I decided to save money and rent a flat together. Ravi had just been politely kicked out of his fifth flat in fewer years; this time, he proclaimed, for putting too much (fried) garlic into his food.

He claimed that he had been asked to leave, politely, for playing (mostly Maghrebi) music too loud, frying his food instead of boiling it, walking about in his undergarments, using too much (fried) spice in his cooking, and not cleaning his windowsin that orderin the past. Of course, those were never the reasons given, Ravi confessed under intensive cross-examination by my (now ex-) wife; the reasons given were always polite ones. Dammit, yaar, he said to me later, this is not a bloody Third World state; it is a civilized country. You think anyone would give you real reasons in a civilized place? On one occasion, he conceded, it might also have had to do with him encouraging his landladys barkative poodle down the stairs at a rather precipitous pace. But, in general, Ravi maintained, his food, music and clothing had a role to play in his gypsy status in rhus. Not that my ex-wife had believed his stories. Can you imagine anyone throwing Ravi out, in any country? she had asked me, alluding to the ease of assurance that Ravi exuded. He must set out to provoke these poor people.

It was while we were doing the rounds looking for places to rentour university background prevented us from going for one of those udlnding ghettoes where Ravis cooking would have been toleratedthat we met Karim. At forty-five, Karim was more than a decade older than us. He had a full flowing beard, speckled with grey. Like Ravi, he was an Indian; like me, he was a Muslim. Unlike me, he believed in God and his prophets, especially the very last one; unlike Ravi, he did not get worked up about what the West had been doing to all the rest, as Ravi liked to put it. But let me not jump the gun. There is probably a MFA rule against it that, I am sure, I would know if I had paid more attention to my MFA girlfriend of yore. Let me commence with our meeting Karim.

This was about a year after my fatal encounter with the cruising patrol car: my separation and divorce did not take place instantly, it need hardly be said. But a year later, divorce filed for, mortgaged flat sold at a slight loss, mortgaged car sold at a significant loss, (almost ex-) wife departed to Ye Olde England, Ravi and I decamped from an overpriced flat-to-rent with a caring property agent showering brochures on us with the avidity of relieved family members strewing rice on the bride. We were late. Our next meeting, with another property agent, was on the other side of the town.

We jumped into the first taxi we came across. Karim was the taxi driver. His beard fooled Ravi into thinking that Karim was from Pakistan, like me, or Afghanistan, like the Italians in our favorite Italian pizzeria, Milano, on Borgmester Erik Skous All. Ravi believes in maintaining good neighborly relations: he might rudely ignore fellow Indians, but he always pulls out his most chaste Urdu, knots it like an old school tie for identification and prestige, and launches into intricate conversations with Pakistanis. Within minutes these conversations dive into private matters with a comfortable inquisitiveness that would do credit to any of my aunts. We were only halfway through town before Karim and Ravi were exchanging the nicknames of their third cousins and remarking on the fact that while Hindu and Muslim names in the subcontinent mostly differ, the nicknames usually tally. Or Ravi was remarking on it; Karim was nodding politely.