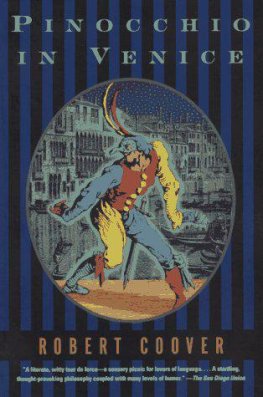

Robert Coover - Pinocchio in Venice

Here you can read online Robert Coover - Pinocchio in Venice full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1997, publisher: Grove Press, genre: Prose. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Pinocchio in Venice

- Author:

- Publisher:Grove Press

- Genre:

- Year:1997

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Pinocchio in Venice: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Pinocchio in Venice" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Pinocchio in Venice — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Pinocchio in Venice" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Robert Coover

Pinocchio in Venice

A SNOWY NIGHT

1. ENTRANCE

On a winter evening of the year 19-, after arduous travels across two continents and as many centuries, pursued by harsh weather and threatened with worse, an aging emeritus professor from an American university, burdened with illness, jet lag, great misgivings, and an excess of luggage, eases himself and his encumbrances down from his carriage onto a railway platform in what many hold to be the most magical city in the world, experiencing not so much that hot terror which initiates are said to suffer when their eyes first light on an image of eternal beauty, as rather that cold chill that strikes lonely travelers who find themselves in the wrong place at the wrong time. "Ah," he groans, staring down the long dreary platform, pallidly lit with fluorescent tubing and garish hotel advertisements and empty now but for a handful of returning skiers disappearing through the glass doors at the far end, if those are indeed glass doors and not merely the swirling fog (he is sharing in his decline the martyrdom of poor Santa Lucia for whom this barbarously functional stazione was named), "whatever was I thinking of!"

He has arrived, as do most Italians, through what foreigners, who prefer always to approach this most remarkable of landing places by sea, think of as the city's back door, but, though Italian-born himself, not by choice or custom but by the simple dictates of the deteriorating weather: the airport was fogged in, he has had to land at Milan, where snow was already beginning to fall, then take the train on from there and in haste lest he be trapped, speeding eastward ahead of the gathering winter storm as though pursued by assassins in coal sacks. The professor, while struggling despairingly through the congestion of Milan with his impossible baggage, had consoled himself with the observation, expressed aloud unfortunately, an embarrassing habit worsening with age, that such a prolongation of the journey would at least provide him more time to adjust to this precipitous return to his native land after so many years abroad and to prepare his mind for entering what was not only, in itself, a universally acknowledged work of art, but also the setting for what he has hoped will be the culmination (just as it was once the springboard) of his own life seen in just those terms: a work of art.

For it was here one day almost a century ago, here on this island then known popularly as the "Island of the Busy Bees," that he, fallen in abject surrender to his own knees, hugged the knees of Virtue herself, and so, but for a forgettable lapse or two (that is to say, he wishes he might be able to forget them: his brief and abortive career in show business, for example, a misadventure which is still almost too painful to recall, even when, as in his latest writings, he has, through excruciating self-examination, transcended it, or sought to), set into motion a life purified of idleness and fantasy and other malignancies of the spirit, a life worthy, he hopes (and in his heart believes), of those knees he once hugged so passionately, wetting them then with tears of gratitude, his infamous nose running with the high fever of what could only be called redemptive grace.

It is this life, as much hers as his, that he is now attempting to celebrate or at least to illuminate in his newest and perhaps (for he has few illusions) final work, a vast autobiographical tapestry in which are woven all the rich, varied strands of his unique personal destiny under the single predominating theme of virtuous love and the lonely ennobling labor that gives it exemplary substance Existenz, as a great philosopher has called it. Monographs abstracted from this work have already, to general and by now familiar acclaim, been published, but the book's conclusion, like rectitude itself in an earlier unhappier time, continues to elude him. And thus, following in the footsteps of his great exemplar and precursor Saint Petrarch, he has been drawn back to this city, somewhat impetuously if truth be told, yet explicably too, seized as he was by the sudden vivid conviction that only by returning here to his, as it were, roots would he find (within himself to be sure, place merely the catalyst) that synthesizing metaphor that might adequately encapsulate the unified whole his life has been, and so provide him his closing chapter. That, together perhaps with a certain restlessness of the spirit, provoked by the alarming symptoms of his onrushing illness: if not now (to wit), when?

It is this opus magnum of his, in all of its physical manifestations (on the hard disk of his portable computer, on two sets of backup diskettes, and on voluminous printout, printout so edited and re-edited he is nothing if not a perfectionist as to resemble a medieval manuscript), that is the principal cause of his present distress. He is able to shift it only a foot or so at a time, carrying a portion of it a few steps ahead, returning for the rest in successive trips, advancing down the windblown platform toward the station proper like a crab, and with the mood of one as well, fatigued and headachy and in something of a stupor still from his unrestful doze aboard the overheated train (in reality, the prolongation of the journey accomplished very little). Where are the porters? Perhaps it is too late. He has no idea what time it is. It is dark, but it has been dark all day. Whichever day it's been: he's not even certain about that, so numbingly interminable has this ill-considered journey become. He is accustomed on his travels to being met everywhere by younger faculty, catered to, treated with the deferential esteem due his age and scholarly distinction (only on the New York-Paris leg of his trip did it occur to him, for example, that he has not reserved a hotel room, something he has almost forgotten how to do by himself), and now, though it has been his express desire to guard his solitude and anonymity on this particular occasion, an occasion he thinks of as reverentially sentimental, a voyage into his secret heart of hearts, as they used to say back at the studio in Hollywood, he nevertheless feels somehow betrayed and quite wrongfully neglected, such that when a porter finally does appear, just as he is wrestling his bags and boxes in through the station doors, the professor, tears smarting at the corners of his eyes, blurts out at him: "Where have you been? I don't need you now, you idiot! Go away!"

"As you wish, sir," replies the porter with an obsequious bow (he is wearing the long-beaked bespectacled Carnival mask of the Plague Doctor under his blue "PORTABAGAGLI" cap, a bit of gratuitous symbolism the professor, in the grip of his strange infirmity and with his bags jammed hopelessly in the intractable station doors, could well do without), and he turns and trudges lugubriously away, pushing his empty trolley ahead of him.

The professor stares out across the desolate station, recalling a monograph he wrote early in his career on "The Tyranny of Perspectivism" and realizing with a sinking heart that he cannot even reach, on his own, the exit doors on the other side, much less some distant but as yet unbooked hotel. "Wait!" he calls out, his voice thin with petulance and self-pity (of course, the hotel will have its own boat, this city is not without its conveniences, even for the solitary traveler). The porter turns and cocks his white snout quizzically from behind his humped back. "To the tourist office, please! Come on, fellow, let's not be all night about it!"

"Can't make the step longer than the leg," mutters the porter sulkily, limping back with agonizing and perhaps mocking deliberation. "So don't fly off the hinges, padrone, he who hurries most arrives last, as they say."

"They also say that life's short, but talk's long," snaps the professor irritably as he watches the porter heave his luggage clumsily onto the trolley. "Be careful now, that's a computer "

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Pinocchio in Venice»

Look at similar books to Pinocchio in Venice. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Pinocchio in Venice and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.

![Bosworth - Italian Venice: a history[Electronic book]](/uploads/posts/book/194557/thumbs/bosworth-italian-venice-a-history-electronic.jpg)