Neel Mukherjee

The Lives of Others

Ma, I feel exhausted with consuming, with taking and grabbing and using. I am so bloated that I feel I cannot breathe any more. I am leaving to find some air, some place where I shall be able to purge myself, push back against the life given me and make my own. I feel I live in a borrowed house. Its time to find my own Forgive me

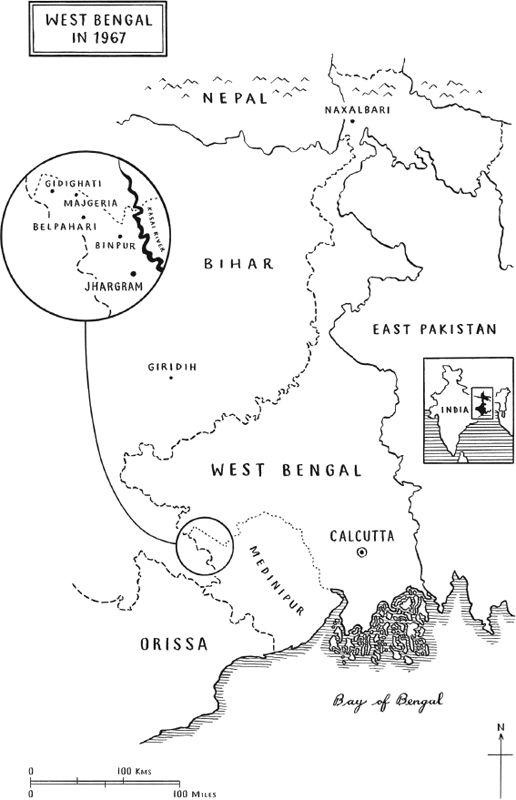

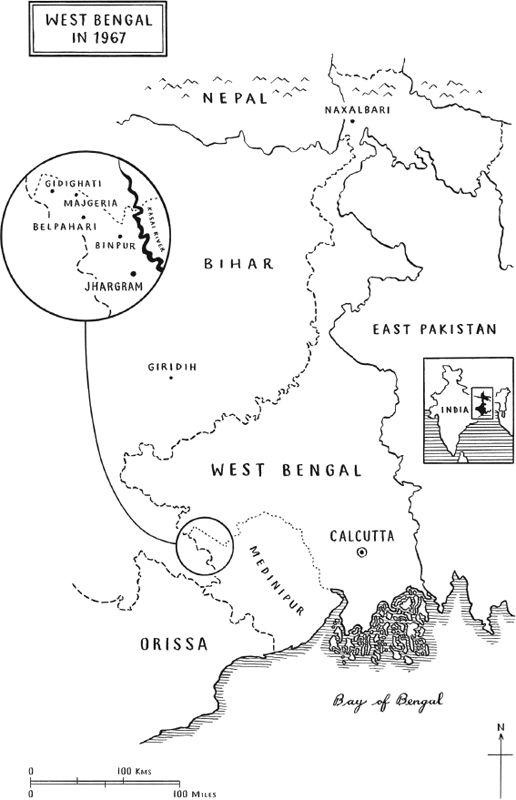

Calcutta, 1967. Unnoticed by his family, Supratik has become dangerously involved in extremist political activism. Compelled by an idealistic desire to change his life and the world around him, all he leaves behind before disappearing is this note

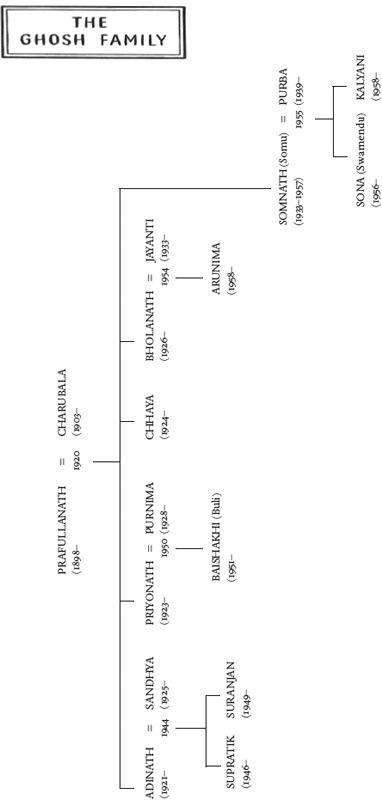

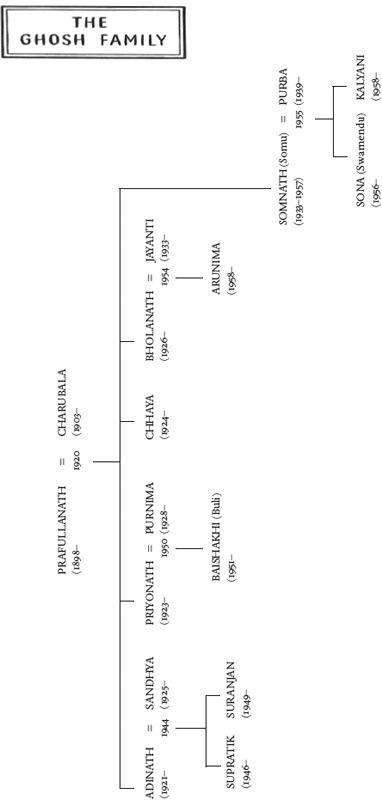

The ageing patriarch and matriarch of his family, the Ghoshes, preside over their large household, unaware that beneath the barely ruffled surface of their lives the sands are shifting. More than poisonous rivalries among sisters-in-law, destructive secrets, and the implosion of the family business, this is a family unravelling as the society around it fractures. For this is a moment of turbulence, of inevitable and unstoppable change: the chasm between the generations, and between those who have and those who have not, has never been wider.

Ambitious, rich and compassionate The Lives of Others anatomises the soul of a nation as it unfolds a family history. A novel about many things, including the limits of empathy and the nature of political action, it asks: how do we imagine our place amongst others in the world? Can that be reimagined? And at what cost? This is a novel of unflinching power and emotional force.

Neel Mukherjee was born in Calcutta. His first novel, A Life Apart (2010), won the Vodafone-Crossword Award in India, the Writers Guild of Great Britain Award for best fiction, and was shortlisted for the inaugural DSC Prize for South Asian Literature. This is his second novel. He lives in London.

How can we imagine what our lives should be without the illumination of the lives of others?

James Salter, Light Years

Its a poor sort of memory that only works backwards.

Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland

. . things are the way they are and when we recognise them, they are the same as when recognised by others or indeed by no one at all.

Daniel Kehlmann, Measuring the World

In historical events what is most obvious is the prohibition against eating the fruit of the tree of knowledge.

Leo Tolstoy, War and Peace

A THIRD OF the way through the half-mile walk from the landlords house to his hut, Nitai Dass feet begin to sway. Or maybe it is the head-spin again. He sits down on the lifeless field he has to cross before he can reach his hut. There isnt a thread of shade anywhere. The May sun is an unforgiving fire; it burns his blood dry. It also burns away any lingering grain of hope that the monsoons will arrive in time to end this third year of drought. The earth around him is beginning to fissure and crack. His eyelids are heavy. He closes them for a while, then, as sleep begins to take him, he pitches forward from his sitting position and jolts awake. Absently, he fingers his great enemy, the soil, not soil any more, but compacted dust. Even its memory of water has been erased for ever, as if it has never been.

He has begged all morning outside the landlords house for one cup of rice. His three children havent eaten for five days. Their last meal had been a handful of hay stolen from the landlords cowshed and boiled in the cloudy yellow water from the well. Even the well is running dry. For the past three years they have been eating once every five or six or seven days. The last few times he had gone to beg had yielded nothing, except abuse and forcible ejection from the grounds of the landlords house. In the beginning, when he had first started to beg for food, they shut and bolted all the doors and windows against him while he sat outside the house, for hours and hours, day rolling into evening into night, until they discovered his resilience and changed that tactic. Today they had set their guards on him. One of them had brought his stick down on Nitais back, his shoulders, his legs, while the other one had joked, Where are you going to hit this dog? He is nothing but bones, we dont even have to hit him. Blow on him and hell fall back.

Oddly, Nitai doesnt feel any pain from this mornings beating. He knows what he has to do. A black billow makes his head spin again and he shuts his eyes to the punishment of white light. All he needs to do is walk the remaining distance, about 2,000 hands. In a few moments, he is all right. Some kind of jittery energy makes a sudden appearance inside him and he gets up and starts walking. Within seconds the panting begins, but he carries on. A dry heave interrupts him for a bit. Then he continues.

His wife is sitting outside their hut, waiting for him to return with something, anything, to eat. She can hardly hold her head up. Even before he starts taking shape from a dot on the horizon to the form of her husband, she knows he is returning empty-handed. The children have stopped looking up now when he comes back from the fields. They have stopped crying with hunger, too. The youngest, three years old, is a tiny, barely moving bundle, her eyes huge and slow. The middle one is a skeleton sheathed in loose, polished black skin. The eldest boy, with distended belly, has become so listless that even his shadow seems dwindled and slow. Their bones have eaten up what little flesh they had on their thighs and buttocks. On the rare occasions when they cry, no tears emerge; their bodies are reluctant to part with anything they can retain and consume. He can see nothing in their eyes. In the past there was hunger in them, hunger and hope and end of hope and pain, and perhaps even a puzzled resentment, a kind of muted accusation, but now there is nothing, a slow, beyond-the-end nothing.

The landlord has explained to him what lies in store for his children if he does not pay off the interest on his first loan. Nitai has brought them into this world of misery, of endless, endless misery. Who can escape whats written on his forehead from birth? He knows what to do now.

He picks up the short-handled sickle, takes his wife by her bony wrist and brings her out in the open. With his practised farmers hand, he arcs the sickle and brings it down and across her neck. He notices the fleck of spit in the two corners of her mouth, her eyes huge with terror. The head isnt quite severed, perhaps he didnt strike with enough force, so it hangs by the still-uncut fibres of skin and muscle and arteries as she collapses with a thud. Some of the spurt of blood has hit his face and his ribcage, which is about to push out from its dark, sweaty cover. His right hand is sticky with blood.

The boy comes out at the sound. Nitai is quick, he has the energy and focus of an animal filled with itself and itself only. Before the sight in front of the boy can tighten into meaning, his father pushes him against the mud wall and drives the curve of the blade with all the force in his combusting being across his neck, decapitating him in one blow. This time the blood, a thin, lukewarm jet, hits him full on his face. His hand is so slippery with blood that he drops the sickle. Inside the tiny hut, his daughter is sitting on the floor, shaking, trying to drag herself into a corner where she can disappear. Perhaps she has smelled the metallic blood, or taken fright at the animal moan issuing out of her father, a sound not possible of humans. Nitai instinctively rubs his right hand, his working hand, against his bunched-up lungi and grabs hold of his daughters throat with both his hands, and squeezes and squeezes and squeezes until her protruding eyes almost leave the stubborn ties of their sockets and her tongue lolls out and her thrashing legs still. He crawls on the floor to the corner where their last child is crying her weak, runty mewl and, with trembling hands, covers her mouth and nose, pushing his hands down, keeping them pressed, until there is nothing.