Lance Olsen

Calendar of Regrets

The author would like to thank the publishers of the following journals and anthologies, in which some of these chapters first appeared in slightly different form: Best New Writing 2007, Black Warrior Review, Brooklyn Rail, Closets of Time, Gargoyle, Detroit: Stories, Iowa Review, Perigee, Serving House, Weber Studies, Writers' Dojo.

Collage/text chapters and photographs created and manipulated by Andi and Lance Olsen.

for Andi,

co-author of it all

Once upon a time I was someone then that stopped.

Laird Hunt, The Exquisite

This too is erotic the anticipation of the pleasure of making sense.

Lyn Hejinian, My Life

To hope is to contradict the future.

E. M. Cioran, All Gaul is Divided

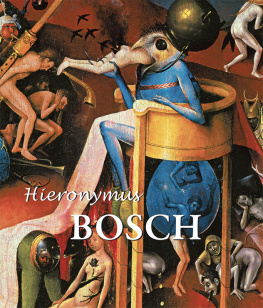

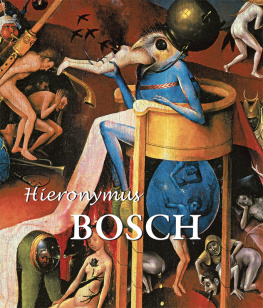

Hieronymus Bosch dabs paintbrush to palette and confers with the small round convex mirror floating alone in an ocean of bonewhite wall on the far side of his studio. Sharpness of eye, thinness of lip, satirical rage, he thinks: his whole family of attributes, God willing, will be out of this mess soon enough. Rotating back to his work at hand, he touches color flecks to the insectile legs rooted in the dwarf's shoulder. Appraises.

Travel is sport for those who lack imagination. Bosch is sure of it. Take, by way of illustration, that huge hideous Groot. That huge hideous Groot does not possess a nose. He possesses a greasy vein-webbed tumor partitioning two puckered purple assholes. A homuncular likeness of him hunches in the dark sky above the rendered Bosch's raised left hand. Groot appears piggish as a gluttonous priest, ears donkey-large with gossip. The heavens churn with hell smoke. Below, the hilly countryside blazes with the firewind of belief.

Yet, despite his mass, the noisome emissary from the Brotherhood of Our Lady cannot stop moving. S-Hertogenbosch to Tilburg, Tilburg to Eindhoven, Eindhoven to Brussels, and back again, busying himself with business. What Groot's sort does not know, cannot fathom, is that movement is nothing more than a forgetting, foreign landscapes forms of amnesia, journeying a process of unstudying.

One must learn to stay put in order to see. Become a place. A precise address. Lot's wife, that salty pillar.

Huge hideous Groot dropped by this morning, unannounced. Bosch is still trying to figure out why. Prattle over coffee before heading to Helmond. A shared prayer for the Virgin through a cheek squirreled with sugar cubes and ginger snaps. Scuttlebutt about Brinkerhoff, the Brotherhood's banker, between slurps. Groot's sticky mouth sounded like a sea-creature oozing in a fishmonger's bucket.

Bosch knew the boob would not recognize himself in the painting. No one ever does. Every man believes it the next who is worthy of scorn. So Bosch left his easel unveiled as the two sat opposite each other like chess players on the two chairs, stiff-backed as Groot's personality, that comprised the better part of Bosch's cramped workroom.

Because behind the heavy green curtains (he has had them manufactured especially for this severity of space) hovers a window out of which Bosch is proud to say he has not peered for almost sixty-six years. His days are nights lit by eleven lamps. Beyond the window hovers a reeking market square through which he cannot at this instant remember ever having ambled, although he has done so to bring his humors into balance every day since he was thirty at precisely two o'clock with his wife, skeletal Aleyt, and every day at precisely five o'clock, alone, in preparation for the evening meal. He cannot remember the neat rows of slender two-story whitewashed and redbrick houses adorned with stepped gables, tiled roofs, glossy black highlights. He cannot remember the cobblestone lanes shiny with horseshit, wet hay, rotting vegetables, foamy piss, shabby beggars, and ballooned rats rigored under the autumnal mizzle, or, as must be the case on this warm summer afternoon, were he to allow himself the luxury of a glance, the fly-hazed heifers dumbly raising their heads not to reflect a little longer throughout the pastures beyond that slide toward infinity beneath a sky sewn from Siberian irises.

Bosch consults the mirror again. He specks ochre along the dwarf's beak sparkly with slobber.

His grandfather was a painter. His father, too. His big brother Goosen. Three of his four uncles. Yet for the life of him Bosch cannot comprehend whence his own style swelled. It resembles that of the other members of his clan not in the least. Unlike them, unlike his peers, from the instant Hieronymus Bosch kissed brush to canvas he took the greatest pleasure in leaving a faintly rough surface behind him that announces this is a picture of my mind's picture, which is, he believes, as it should be: the world alla prima, a single sketchless application.

Underpainting, he is convinced, is the technique of genius gimping.

The skin of any one of his paintings is more Bosch, more fully himself, than the graying disgrace presently stretched across his bones. This is why he has signed only seven in his career, and then only under duress, only because that is what it took to cache coins to pay bills to paint further paintings. Aleyt sometimes asks why he does not want additional wealth, a larger house, a more elegant wardrobe, although she already knows she already knows the answer. She is the one, after all, who taught it to him. It is the same reason he writes no letters, keeps no journals. Such things are paper children, and why produce paper children when one refuses to produce the screechy, selfish, reeking variety?

Sail nowhere save among the continents of your own soul, and, when your body at long last gives up its war upon you, sloughs away, returning you to infancy, the final hinged panel of the polyptych called yourself having been reached and rushed beyond, leave the useless remainder behind on the wicked midden heap it is.

Let your stunned spirit lift. Drift. Bolt. Soar. Because

Because

Because, in a phrase: Doeskin brown. Watermelon red. Sandy summer soil the tone of sandkage. These are the only exotic municipalities a man needs visit during his delay on earth, so long as he pays attention, keeps his inner eyes open, learns to listen to himself, which is to say to the noise light makes within the head.

Life's foe is distraction. This is why Bosch has never stepped beyond the lush pastures embracing s-Hertogenbosch. He does not see the advantage. Journey is attempted breakout, and yet, down behind the liver, the spleen, every human knows no one leaves this town, any of them, alive.

Bosch mentioned as much to Groot in passing. He could not help taking note as he did so of the pink speckles constellating the emissary's bald pate, the bad hide beneath his patchy fog of beard. Their peculiar meeting lasted less than half an hour. A rap arrived upon the front door as the town clock tolled ten. From his studio, where Bosch had been orbiting his easel, endeavoring to see his self-portrait from the vantage point of another solar system, he could hear clatter and commotion in the foyer, his wife's artificial trill, Groot's bass outshout caving into that chronic gluey cough of his. Hope cringed. Bosch could hear Aleyt usher in the intruder, offer him a cup of coffee, could hear Groot accept. Hope bit its own cheek. Aleyt called brightly to her husband that his colleague was here. Bosch watched hope hobble away.

Aleyt showed Groot into the studio where Bosch set down his brush, dabbed his fingers with a nearby rag, revolved stiffly on stiff knees, reached out, and wobbled Groot's chubby hand. Aleyt disappeared, reappeared with a hectic silver serving tray, then vanished for good, leaving the painter to fend for himself. He felt like the last soldier on a battlefield, the enemy of thousands descending.