Nadifa Mohamed

Black Mamba Boy

FOR

NADIIFO,

DAHABO,

AXMED,

XASAN,

SHIDANE,

AND ALL THE OTHERS WE LOST

Now you depart, and though your way may lead

Through airless forests thick with hagar trees,

Places steeped in heat, stifling and dry,

Where breath comes hard, and no fresh breeze can reach

Yet may God place a shield of coolest air

Between your body and the assailant sun.

Gabay by Maxamed Cabdulle Xasan

O troupe of little vagrants of the world, leave your footprints in my words.

from Stray Birds by Rabindranath Tagore

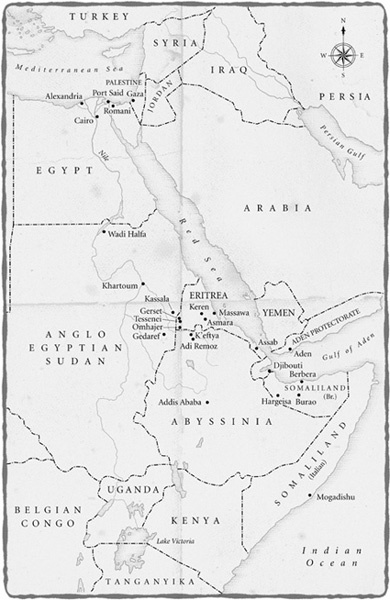

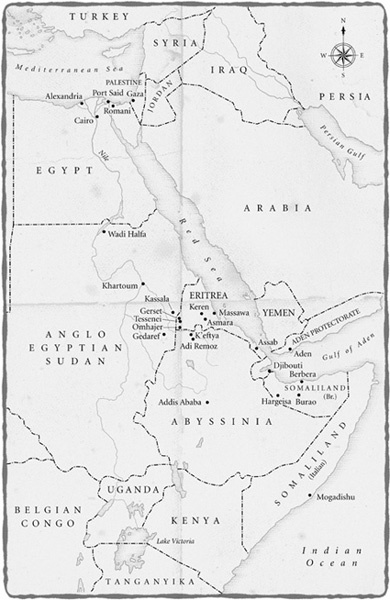

ADEN, YEMEN, OCTOBER 1935

The muezzins call startled Jama out of his dream, and he pulled himself up to look at the sun rising over the cake-domed mosques, the gingerbread Adeni apartments glowing at their tips with white frosting. The black silhouettes of birds looped high in the inky sky, circling around the few remaining stars and the pregnant moon. The black planets of Jamas eyes roamed over Aden the busy, industrial Steamer Point; Crater, the sandstone old town, its curvaceous dun-colored buildings merging into the Shum Shum volcanoes; the Maalla and Sheikh Usman districts, white and modern, between the hills and sea. Wood smoke and infants cries drifted up as women took a break from preparing breakfast to perform their dawn prayers, not needing the exhortations of the old muezzin. A vultures nest encircled the ancient minaret, the broken branches festooned with rubbish, the nest corrupting the neighborhood with the stench of carrion; the attentive mother fed rotting morsels to her chirruping chicks, her muscular wings unhunched and at rest beside her. Jamas own mother, Ambaro, stood by the roof edge, softly singing a song in her deep and melodious voice. She sang before and after work, not because she was happy but because the songs escaped from her mouth, her young soul roaming outside her body to take the air before it was pulled back into drudgery.

Ambaro shook the ghosts from her hair and began her morning soliloquy. Some people dont know how much work goes into feeding their ungrateful guts, think they are some kind of suldaan who can idle about without a care in the world, head full of trash, only good for running around with trash. Well, over my dead body, I dont grind my backbone to dust to sit and watch filthy-bottomed boys roll around on their backs.

These poems of contempt, these gabays of dissatisfaction greeted Jama every morning. Incredible meandering streams of abuse flowed from his mothers mouth, sweeping the mukhadim at the factory, her son, long-lost relatives, enemies, men, women, Somalis, Arabs, Indians into a pit of damnation.

Get up, stupid boy, you think this is your fathers house? Get up, you fool! I need to get to work.

Jama continued to loll around on his back, playing with his belly button. Stop it, you dirty boy, youll make a hole in it. Ambaro slipped off one of her broken leather sandals, and marched over to him.

Jama tried to flee but his mother dived and attacked him with stinging blows. Get up! I have to walk two miles to work and you make a fuss over waking up, is that it? she raged. Go then, get lost, you good-for-nothing.

Jama blamed Aden for making his mother so angry. He wanted to return to Hargeisa, where his father could calm her down with love songs. It was always at daybreak that Jama craved his father, all his memories were sharper in the clean morning light, his fathers laughter and songs around the campfire, the soft, long-fingered hands enveloping his own. Jama couldnt be sure if these were real memories or just dreams seeping into his waking life, but he cherished these fragile images, hoping that they would not disappear from him like his father had. Jama remembered traversing the desert on strong shoulders, peering down on the world like a prince, but already his fathers face was lost to him, hidden behind stubborn clouds.

Along the dark spiral steps came the smell of anjeero; the Islaweynes were having breakfast. ZamZam, a plain teenaged girl, used to bring Jama the mealtime scraps. He had accepted them for a while until he heard the boys in the family call him Haashishki, Trash Can. The Islaweynes were distant relatives, members of his mothers clan, who had been asked by Ambaros half brother to take her in when she arrived alone in Aden. They had done as promised but it soon became clear that they expected their bedu cousin to be a servant: cooking, cleaning, and giving them the appearance of gentility. Within a week Ambaro had found work in a coffee factory, depriving the Islaweynes of their new status symbol and unleashing the resentment of the family. Ambaro was made to sleep on the roof, she was not allowed to eat with them unless Mr. Islaweyne and his wife had guests around; then they were all smiles and familial generosity, Oh, Ambaro, what do you mean Can I? Whats ours is yours, sister!

When Ambaro had saved enough to bring her six-year-old son to Aden, Mrs. Islaweyne had fumed at the inconvenience and made a show of checking him for things that could infest or infect her children. Her gold bangles had clanked around as she looked for nits, fleas, skin diseases; she shamelessly pulled up his maawis to look for worms. Even after Jama had passed her medical exam, she glared at him when he played with her children and whispered to them to not get familiar with this boy from nowhere. Five years later, Ambaro and Jama still lived like phantoms on the roof, leaving as few traces of their presence as possible. The neatly stacked piles of laundry that Ambaro washed and Jama pegged out to dry were the only banners of their existence to the family.

Ambaro left for the coffee factory at dawn and didnt return until dark, leaving Jama to float around the Islaweyne home feeling unwelcome, or to stay out in the streets with the market boys. Outside the sky had brightened to a watery turquoise blue, and Somali men asleep by the roadside began to rouse, their afros full of sand, while Arabs walked hand in hand toward the suq. Jama fell in behind a group of Yemenis wearing large gold-threaded turbans and beautiful, ivory-handled daggers in their belts. He ran his hands along the warm flanks of passing camels being led to market, their extravagant eyelashes batting in appreciation at his gentle stroke, and when they overtook him their swishing tails waved goodbye. Men and boys shuffled past ferrying vegetables, fruits, breads, meats, in bags, in their hands, on their heads, to and from the market, crusty flatbread tucked under their arms like newspapers hot off the press. Butterflies danced, enjoying their morning flutter before the day turned unbearably hot and they slept it off inside sticky blossoms. Incense lingered on the skin and robes of the hammals as they pushed their wheelbarrows through the narrow, potholed alley, each man cocooned in the perfume of his home. Leaning against the warm wall, Jama closed his eyes and imagined curling up in his mothers lap and feeling the reverberations of her songs as they bubbled up from deep within her body. He sensed someone standing over him, a small hand rubbed the top of his head, and he opened his eyes to see Abdi and Shidane grinning down at him. Abdi was the nine-year-old, gappy-toothed uncle of eleven-year-old gangster Shidane. Abdi held out a chunk of bread and Jama swallowed it down.

The black lava of the Shum Shum volcanoes loomed over them when they reached the beach. Market boys of all different hues, creeds, and languages gathered at the beach to play, bathe, and fight. They were a roll call of infectious diseases, mangled limbs, and deformities. Jama called Shalom! to Abraham, a shrunken Jewish boy who used to sell flowers door-to-door with him. Abraham waved and took a running leap into the water. Shidanes malnutrition-blond hair looked transparent in the sunlight and Abdis head jiggled from side to side, too big for his paltry body, as he ran into the surf. These two perfect sea urchins spent their days diving for coins. Jama wanted them to take him out to sea, so he collected wooden planks washed up on the shore, and called the gali gali boys to attention.