For my god-sister, Carrie Mikel, and for my godfather, John Pilato.Both deserve more than just a book dedicated in their names.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

WHEN A WORK OF THIS SCOPE is being written, no one author can claim credit for all its contents. The words are mine; the work is mine; the interpretations are mine. This book represents countless hours of writing, rewriting, worry, and sweat. Yet Santera is an oral faith, and its true secrets are not to be found in the myriad volumes already on the market; its mysteries are found in the hearts and souls of those who practice this religion.

For this book, I am in great debt to my godfather, Eshuleri Bolafun ( John Pilato), for his patience and thorough instruction. He teaches not with the mouth but with his heart, and his love for this religion is reflected in all that he does. To Naomi Alejandro, Christine Jaffe, Michael Cabrera, Akin Babatunde, Ogndei (Evaristo Perz), and many others, I am in debt for my own vast knowledge of eb.

My publisher, Inner Traditions, cannot go without acknowledgment; I must thank Jon Graham and Laura Schlivek for their countless hours of hard work as they turned this manuscript (and my previous work) from a dream into reality. My former copy editor, Susannah Noel, was a tireless tyrant (said in love, of course) when it came to polishing my previous book, The Secrets of Afro-Cuban Divination. I learned so much by working with her; how can I thank her for pushing me, and my writing skills, to the limit?

Doris Troy, the copy editor for this book, was just as thorough, and gave Ob: Oracle of Cuban Santera the final bit of polish it needed to become the masterpiece it is. Thank you Doris! Finally, I would not be in this religion at all except for Oy, who claims and guides my head in life; if I owe anything to anyone, I owe all to her. She has given me a life where I thought I had none, and there is no greater gift than that. Ach to you all.

Introduction

Introduction

Beyond the Middle Passage

When my head is on my shoulders, my feet in salty waters, and my thoughts extend beyond the horizon, there is no doubt in my mind that I stand facing the ocean.

A proverb from the diloggn, bab Eji Ogbe

STANDING ON THE ATLANTIC SHORE and gazing at the oceans endless surf, I know peace and fear. There are no other words to describe the feelings that Olokun, the bitter sea, evokes. I stand at the crest of land and sea, where waves roll relentlessly against the coastline, hungrily sucking sand to sea before churning it once more against the shore. I am still as she laps at my feet. The tide is receding slowly, yet the waves are ceaseless and the sand moves constantly. My footing dissolves; I shift my weight back and to the side to keep my balance. Blocking the morning sun with cupped palms, my eyes follow the path of bubbling sunlight over the water and into the horizon; it ends in the blue ocean and the bluer sky, into a gentle, sloping curve that slips from view. I am lost in this moment, lost with the sand amid foaming waves. Eternity lives here, in the ocean, and it is to this place that I come, again and again, to rest, to meditate, to cleanse, to recharge. I yearn to mingle with the natural forces as they, too, merge and mingle with each other.

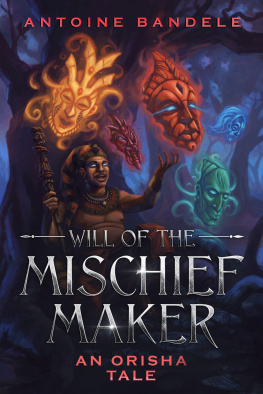

Today I have not come alone; my godmother, Jackye, and her friend Josephine have brought me. Both are santeras, priestesses of an Afro-Cuban faith known as Santera, a religion that survived more than four hundred years of slavery and persecution by white and Hispanic slave lords. It is a spirituality that nourished the souls of those oppressed for no reason other than the silky blackness of their skins. Torn from their homelands, sold and bought like chattel, raped, abused, beaten, and packed into the filthy cargo bays of slave-trading ships, the followers of the orishas (spirits) came to the New World with no more than the ach, the power, of the orishas within their heads. Those who had time swallowed the sacred shells of their gods, taking their physical forms on earth into their bodies; thus were they able to hide their spirits from their captors. Inevitably, these relics passed through their bodies; once again they swallowed them and held them secretly in their bellies. For months priests and priestesses suffered in darkness, bound in iron chains as seamen guided the marine prisons over the ocean. Some mortally mangled themselves to escape these bonds, finding release and peace only as they flung themselves over the ships bow, consigning their lives into the oceans icy grip, Olokuns womb. The rest suffered agonizing pain and torment, praying to her for strength, for release, for safe passage.

Of the hundreds of blacks crammed into cramped quarters, only a few survived each crossing: the determined, the strong, the devoted. Those who died were tossed overboard by the ships crew without care or concern, left to sink to the cold, salty depths. Yet the same qualities that enabled those few to endure also enabled the orishas to survive. Priests of the white Christ tried in vain to convert the African souls. Although they had neither the morals nor the strength to destroy the sin of slavery, they assuaged their own festering guilt by baptizing blacks in the name of Jesus. But while the slave masters could coerce the bodies of their servants, they could not conquer their Yoruba spirit. The holy saints, say some, looked down in pity and despair at what their own people were doing; and the orishas, in their infinite wisdom, carried the followers through the hardships of slavery. In secret, in hiding, disguising their gods behind the willing masks of the saints, priestesses and priests of the orishas continued to nourish the spirits, and the orishas, in return, sustained their followers through the centuries, helping them to evolve, to grow in a prison that was not of their making, in a world that they did not want.

History is a fragile cloth, its threads easily broken, its patterns dulled by the past that created it. Nature is cruel, destroying what she has wrought with her own hands. Time, even time devours his own children. The cries of our ancestors, however, still echo in the angry, crashing waves. We can hear them, and remember, if we listen. We must listen.

It has been more than four centuries since the first slaves were brought to the New World, and although slavery has been abolished, their descendants are still oppressed by a society that disapproves of not only their skin color, but also their native spirituality. I stand with my elders at the oceans edge, the end of the Middle Passage. My godmother, Jackye, is a priestess of Obatal, mother and father to the earth, the great ruler of the heights sent forth by Oldumare to create upon the watery void. Josephine, an elder, a Puerto Rican santera, is a priestess of Yemay, the orisha brought forth from Olokuns depths as Obatal chained her from land. Unable to resist the supreme deitys sanctions, yet too vast to be restrained by Obatals chains, Yemay was born from Olokuns prison; she became the owner of the oceans waves and of all the fresh water upon the earth. We had come to honor this mighty goddess, the worlds queen. Josephine and Jackye had brought an array of offerings: watermelons, pork rinds, and dark molassesdelicacies of the orisha.

Unknown to them, I had brought my hopes and my fears. I am white and entering an African religion; and although my godmother herself is white, I could not help but wonder if I really belonged in such a faith. Before the sea I suddenly became frightened. I could imagine the souls of the ancestors out there, embraced in Olokuns icy grip. I could imagine their pain, their terror, as they were flung carelessly into a watery abyss. I was in awe of them, of the oceans vast depths, of its strengths and powers. Shaking, I stepped back from the water.

Next page

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments