Published in 2015 by Britannica Educational Publishing (a trademark of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.) in association with The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Copyright 2015 by Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopdia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved.

Rosen Publishing materials copyright 2015 The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved

Distributed exclusively by Rosen Publishing.

To see additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, go to http://www.rosenpublishing.com

First Edition

Britannica Educational Publishing

J. E. Luebering: Director, Core Reference Group

Anthony L. Green: Editor, Comptons by Britannica

Rosen Publishing

Hope Lourie Killcoyne: Executive Editor

John Murphy: Editor

Nelson S: Art Director

Nicole Russo: Designer

Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager

Amy Feinberg: Photo Researcher

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Murphy, John.

Gods & goddesses of the Inca, Maya, and Aztec Civilizations/edited by John Murphy.

pages cm.(Gods and goddesses of mythology)

Includes bibliographic references and index.

ISBN 978-1-62275-397-0 (eBook)

1. Inca mythologyJuvenile literature. 2. Maya mythologyJuvenile literature. 3. Aztec mythologyJuvenile literature. 4. Aztec godsJuvenile literature. 5. Maya godsJuvenile literature. I. Title.

F1219.76.R45 M87 2015

398.2d23

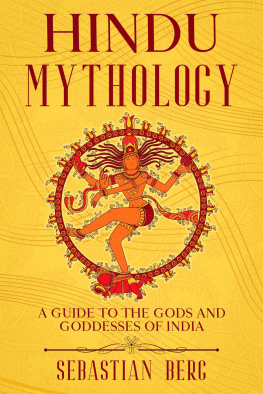

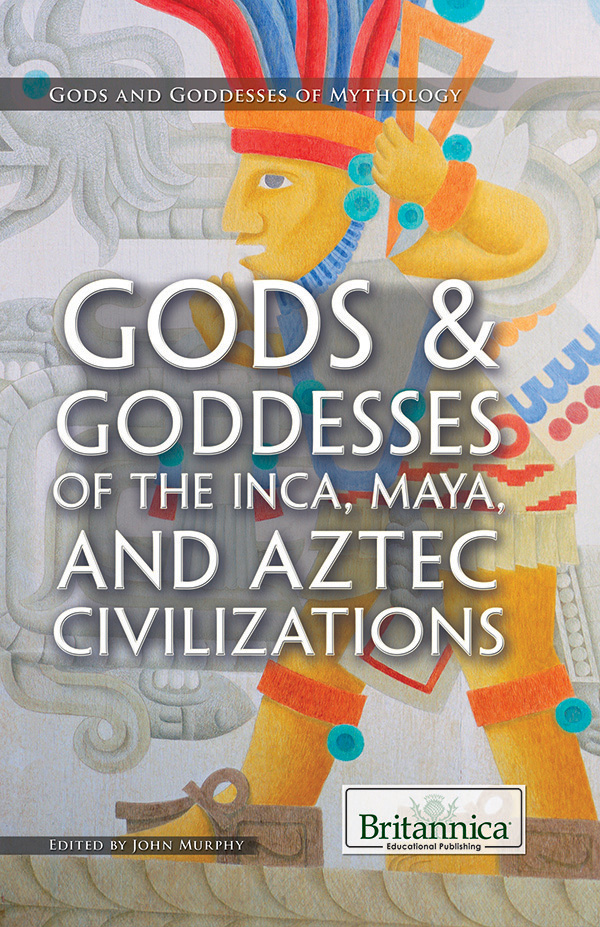

On the cover: The Aztec feathered serpent deity Quetzalcoatl is depicted here. A feathered serpent deity was worshipped by numerous ethno-political groups throughout Mesoamerican history, including the Maya and Aztecs. DEA/G. Dagli Orti/De Agostini/Getty Images

Interior pages graphic iStockphoto.com/DHuss

CONTENTS

A carving of the Mayan and Aztec feathered serpent god Quetzalcatl appears on the side of the Temple of Quetzalcatl in Teotihuacn in Mexico. Gordon Galbraith/Shutterstock.com

T he term Mesoamerica denotes the part of Mexico and Central America that was civilized in pre-Spanish times. In many respects, the American Indiansincluding the Maya, Aztec, and Inca civilizationswho inhabited Mesoamerica were the most advanced native peoples in the Western Hemisphere. The northern border of Mesoamerica runs west from a point on the Gulf Coast of Mexico above the modern port of Tampico, then dips south to exclude much of the central desert of highland Mexico, meeting the Pacific Coast opposite the tip of Baja (Lower) California. On the southeast, the boundary extends from northwestern Honduras on the Caribbean across to the Pacific shore in El Salvador. Thus, about half of Mexico, all of Guatemala and Belize, and parts of Honduras and El Salvador are included in Mesoamerica (the Inca, though based in what would become modern-day Peru and controlling territory running along much of South Americas Pacific Coast, are nevertheless considered a Mesoamerican civilization).

Geographically and culturally, Mesoamerica consists of two strongly contrasted regions: highland and lowland. The Mexican highlands are formed mainly by the two Sierra Madre ranges that sweep down on the east and west. Lying athwart them is a volcanic cordillera stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific. The high valleys and landlocked basins of Mexico were important centres of pre-Spanish civilization. In the southeastern part of Mesoamerica lie the partly volcanic ChiapasGuatemala highlands. The lowlands are primarily coastal. Particularly important was the littoral plain extending south along the Gulf of Mexico, expanding to include the Petn-Yucatn Peninsula, homeland of the Mayan peoples.

The extreme diversity of the Mesoamerican environment produced what has been called symbiosis among its subregions. Interregional exchange of agricultural products, luxury items, and other commodities led to the development of large and well-regulated markets in which cacao beans were used for money. It may have also led to large-scale political unity and even to states and empires. High agricultural productivity resulted in a nonfarming class of artisans who were responsible for an advanced stone architecture, featuring the construction of stepped pyramids, and for highly evolved styles of sculpture, pottery, and painting.

The Mesoamerican system of thought, recorded in folding-screen books of deerskin or bark paper, was perhaps of even greater importance in setting them off from other New World peoples. This system was ultimately based upon a calendar in which a ritual cycle of 260 (13 20) days intermeshed with a vague year of 365 days (18 20 days, plus five nameless days), producing a 52-year Calendar Round.

Mesoamerican religion, called Christo-pagan by anthropologists, is a complex syncretism of indigenous beliefs and the Christianity of early Roman Catholic missionaries. A hierarchy of indigenous supernatural beings (some benign, others not) have been reinterpreted as Christian deities and saints. Mountain and water spirits are appeased at special altars in sacred places by gift or animal sacrifice. Individuals have companion spirits in the form of animals or natural phenomena, such as lightning or shooting stars. Disease is associated with witchcraft or failure to appease malevolent spirits.

Religious life was geared to the ritual cycle of the Calendar Round. The Mesoamerican pantheon was associated with the calendar and featured an old, dual creator god; a god of royal descent and warfare; a sun god and moon goddess; a rain god; a culture hero called the Feathered Serpent; and many other deities. Also characteristic was a layered system of 13 heavens and nine underworlds, each with its presiding god. Much of the system was under the control of a priesthood that also maintained an advanced knowledge of astronomy.

Mesoamerican religion is exceptionally rich in mythology. Myths are symbolic narratives, usually of unknown origin and at least partly traditional, that ostensibly relate or attempt to explain and make sense of actual events or natural phenomena. Myths are especially associated with religious belief. They are distinguished from symbolic behaviour (cult, ritual) and symbolic places or objects (temples, icons), but provide the spiritual narrative that underpins both sacred ritual and the sacred places in which such rituals are enacted.

In essence, myths are specific accounts of gods or superhuman beings involved in extraordinary events or circumstances in a time that is unspecified but which is understood as existing apart from ordinary human experience. Few world mythologies exist further beyond the ordinary and everyday than those of the Maya, Aztec, and Inca, and the same is true of their deities and spiritual practices. In these pages, readers will encounter the wondrously complex, sophisticated, and cosmically synchronized pantheon and mythology of the Maya, Aztec, and Inca. Sharing certain common cultural traits and traditions, but glittering with fascinating and unique variations and elaborations on these core beliefs, each of the great Mesoamerican civilizations presents an enthralling array of gods, goddesses, myths, practices, rituals, holidays, and beliefs. Awaiting the reader is a rich treasury of story and drama, both earthly and celestial, human and divine.