Contents

Guide

Page List

Kabbalah

Kabbalah

A Very Short Introduction

JOSEPH DAN

Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that

further Oxford Universitys objective of excellence

in research, scholarship, and education.

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Copyright 2006 by Joseph Dan

Published by Oxford University Press, Inc.

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

www.oup.com

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise,

without the prior permission of Oxford University Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dan,

Joseph, 1935

Kabbalah : a very short introduction / Joseph Dan. p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-19-530034-5

ISBN-10: 0-19-530034-3

1. Cabala I. Title.

BM525.D355 2005

296.16dc22 2005017169

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper

Contents

Every author of a very short introduction is faced with the difficult task of finding a way to present his subject in a brief and coherent manner, addressing readers who seek only the basic, yet most important, aspects of the discipline to which the book is dedicated. In the case of the kabbalah, however, there is an added difficulty: many readers will seek in the few pages of this book not only new information, but also a confirmation of their own impression of what the kabbalah is. Some will even, knowingly or unknowingly, seek here a description of what the kabbalah should be. For fifty years I have been trying to respond to the question what is the kabbalah? And, in many cases my answer was accepted with disappointment or even resentment: this is not what I believe that the kabbalah is, and certainly it is not what I feel that the kabbalah should be.

The term kabbalah has never been used as often and in so many contexts as it is today, yet now, as in the past, it does not have a real, definite one meaning. From its early beginnings, it has been used in a wide variety of ways. Every medieval kabbalist gave the term his own meaning, which differed slightly or meaningfully from the others. In modern times numerous Jewish and Christian theologians, philosophers, and even scientists have used it in various, sometimes contradictory, ways. It has been an expression of strict Jewish orthodoxy as well as a vehicle for radical, innovative worldviews. The explanation of the meaning of the term must, therefore, be defined within a clear, historical context, stating the time, place, and culture that used it in the past or is using it today. From the point of view of the historian of religious ideas there is no true meaning that is above all others. This short introduction is intended, therefore, to present some of the most prominent characteristics of the different phenomena that were described as kabbalistic in various periods, countries, and cultural contexts.

Our libraries contain many hundreds of works of kabbalah, printed or still in manuscript form. And, beside these, there are thousands of workscollections of sermons, ethical treatises, and commentaries on the scriptures and the Talmudthat use a little or more kabbalistic terminologies and ideas. As a result, there is hardly a Jewish idea that cannot be described as kabbalistic with some justification, as most of these ideas are found in works that use kabbalistic terminology. How can one distinguish between a traditional Jewish ethical norm and a kabbalistic one? Today, it often seems that designating an idea as kabbalistic makes it more welcome to outsiders than if it were described as Jewish. The main work of the medieval kabbalah, the book Zohar, contains 1,400 pages that deal with every conceivable subject. There is nothing that cannot be confirmed by a quotation from the Zohar. A friend of mine who was teaching kabbalah at a university in California in the 1960s produced a beautiful quote from the Zohar to confirm that it is forbidden to study the kabbalah without, at the same time, smoking pot, and he demanded that his students do so in class. I failed in my attempt to persuade him to change his attitude; my authority could not compete with that of the Zohar as he understood it at that time. This small book should therefore be regarded as a subjective selection, augmented by my experience as a historian of religious ideas, of the most prominent meanings attached to the term kabbalah through the ages, without designating any of them as more truthful than the others. As for the deluge of meanings given to the term in contemporary culture, only a future historian will be able to distinguish between the ephemeral and the enduring ones.

Cambridge, Massachusetts, May 2005

Kabbalah

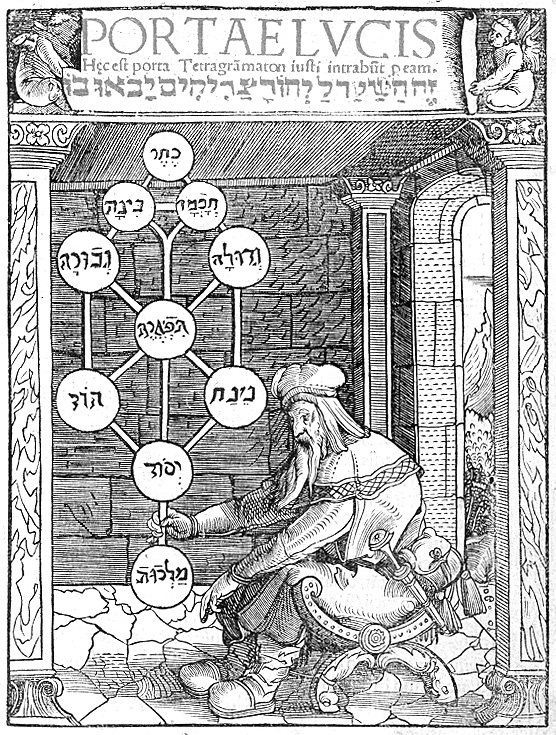

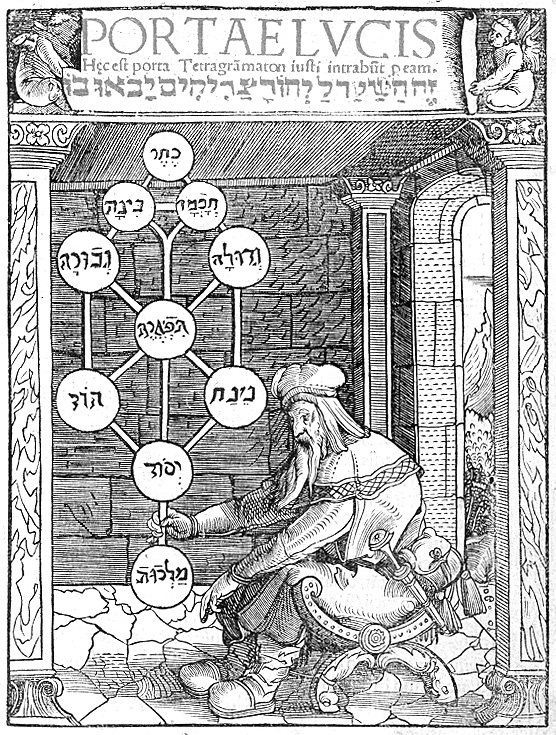

1 A Latin translation of Shaaey Ora (The Gates of Light), one of the most influential presentations of the kabbalistic world-view, written by Joseph Gikatilla in the thirteenth century.

1

Kabbalah: The Term and Its Meanings

A visitor to the State of Israel is confronted by kabbalah several times every day. When he enters a hotel, he is obligated to face a desk, behind which a large sign reads Kabbalah; in English, the same sign reads Reception. When he purchases anything or pays for a service he receives a piece of paper on which the word Kabbalah is written in large Hebrew letters. If there is an English translation on that piece of paper, it reads Receipt. The term will pop up in scores of contexts. If he is invited to a reception, the Hebrew term for the event is kabbalat panim (literally, receiving the face). If he wishes to visit a bank or a government office he must first check the kabalat kahalthe hours in which clerks receive the public, the equivalent of the English open. Every professor, of any discipline, is engaged every week in a kabbalistic hour, sheat kabbalah, that is, office hour, in which his door is open to students. The verb kbl is present in every other sentence in Hebrew, meaning simply to receive. Judging by their behavior, the Hebrew-speaking Israelis seem to be oblivious to the depth of their immersion in mysticism, and treat kabbalah as a simple, mundane word in their language. In a religious context, the key sentence in which this word is used is found in the opening phrase of the talmudic tractate avot, one of the most popular rabbinic Hebrew texts, which was probably formulated in the second century CE. The first section of this tractate describes the traditional chain of Jewish law and religious instruction, which was transmitted from generation to generation. The first stage of this transmission, as described in this tractate, is: Moses received [kibel] the Torah on [Mount] Sinai and transmitted it to Joshua, who [transmitted it] to the Elders [of Israel] ; the text goes on to describe the oral transmission of this tradition to the judges, the prophets, and the early sages of the Talmud. This paragraph was used for nearly two thousand years to validate Jewish tradition as a whole, fixing the Mount Sinai revelation as the point of origin, deriving legitimacy from the sanctity of that event. The term torah in this sentence was understood to mean everythingscriptures, the law (halakhah), the rules of ethics, the expounding of scriptural verses (midrash)everything related to truth of divine origin. Some even said that everything that a scholar might innovate was given by God to Moses: what may seem to be an innovative, brilliant religious observation was already known to Moses, informed by God in that all-encompassing revelation. What Moses received on that occasion is kabbalahtradition, which in this context acquired the particular meaning of sacred tradition of divine origin, part of which is found in writing (scriptures), and part transmitted orally from generation to generation by the religious leaders of the Jewish people.