Sign up to receive news and special offers from Shambhala Publications.

Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala.

A C. G. JUNG FOUNDATION BOOK

The C. G. Jung Foundation for Analytical Psychology is dedicated to helping men and women to grow in conscious awareness of the psychological realities in themselves and society, find healing and meaning in their lives and greater depth in their relationships, and to live in response to their discovered sense of purpose. It welcomes the public to attend its lectures, seminars, films, symposia, and workshops and offers a wide selection of books for sale through its bookstore. The Foundation also publishes Quadrant, a semiannual journal, and books on Analytical Psychology and related subjects. For information about Foundation programs or membership, please write to the C. G. Jung Foundation, 28 East 39th Street, New York, NY 10016.

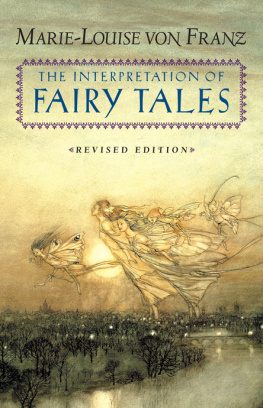

THE INTERPRETATION OF FAIRY TALES

REVISED EDITION

Marie-Louise von Franz

SHAMBHALA

Boulder

2017

Shambhala Publications, Inc.

4720 Walnut Street

Boulder, Colorado 80301

www.shambhala.com

1970, 1973, 1996 by Marie-Louise von Franz

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Franz, Marie-Louise von, 1915

The interpretation of fairy tales / Marie-Louise von Franz.

Rev. ed., 1st ed.

p. cm.

A C. G. Jung Foundation book

Rev. ed. of: An introduction to the interpretation of fairy tales. 1987 printing, 1970.

Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index.

eISBN 9780834840843

ISBN 9780877735267 (alk. paper)

1. Fairy talesHistory and criticism. 2. Psychoanalysis and folklore. I. Franz, Marie-Louise von, 1915 Introduction to the interpretation of fairy tales. II. Title.

GR550.F714 1996 95-25815

398.09dc20 CIP

This book resulted from lectures which I gave in English at the C. G. Jung Institute more than twenty years ago. Based upon a recording of the lectures, it was first published in English in 1970.

In these lectures, I summarized for the students the experience I had gained through my contributions of interpretation to the work of Hedwig von Beit in Symbolik des Mrchens. Apart from some early studies from the Freudian school, as well as some short essays by Alfons Maeder, Franz Riklin, and Wilhelm Laiblin, no interpretations of fairy tales had been published by Jungian authors at that time. That is why it was my primary intention to open up the archetypal dimension of fairy tales to the students. For this reason, the ethnological and folkloristic aspects are only touched upon, which is not meant to imply, however, that I view them as unimportant.

Since then, there has been a real blossoming of fairy tale interpretation from the standpoint of depth psychology. From the Freudian school, primarily Bruno Bettelheims book The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales should be mentioned. From the Jungian school, so many books have been published that I cannot name them all here. Although it is not my intention to assail colleagues by name, I would nevertheless like to express a very personal opinion here. In many so-called Jungian attempts at interpretation, one can see a regression to a very personalistic approach. The interpreters judge the hero or heroine to be a normal human ego and his misfortunes to be an image of his neurosis. Because it is natural for a person listening to a fairy tale to identify with the main character, this kind of interpretation is understandable. But such interpreters ignore what Max Lthi found to be essential for magical fairy tales, namely, that in contrast to the heroes of adventurous sagas, the heroes or heroines of fairy tales are abstractionsthat is, in our language, archetypes. Therefore, their fates are not neurotic complications, but rather are expressions of the difficulties and dangers given to us by nature. In a personalistic interpretation, the very healing element of an archetypal narrative is nullified.

For example, the hero-child is nearly always abandoned in fairy tales. If one then interprets his fate as the neurosis of an abandoned child, one ascribes it to the neurotic family novel of our time. If, however, one leaves it embedded within its archetypal context, then it takes on a much deeper meaning, namely that the new God of our time is always to be found in the ignored and deeply unconscious corner of the psyche (the birth of Christ in a stable). If an individual has got to suffer a neurosis as a result of being an abandoned child, he or she is called upon to turn toward the abandoned God within but not to identify with his suffering.

Hans Giehrl, in Volksmrchen und Tiefenpsychologie, makes what I view to be a partially justified reproach of depth-psychology interpreters, namely that they transfer their own subjective problems onto the fairy tales, where they are not to be found at all. As in all scientific work, the subjective factor can never be entirely excluded. But I believe that by using the basic tool of mythological amplification, one can hold in check such subjectivism and, to some extent, thereby reach a generally valid interpretation.

Another tool we can use to reach a certain level of objectivity is to take the context into consideration. Here, too, Giehrl expresses criticism, though in this respect I do not agree with him. He believes that because variations sometimes include contrary motifs and for this reason are omitted, the objectivity of contextual research is impaired. But if one goes into this more deeply, then one can see that each contrary motif changes the whole context and therefore proves just the opposite. The Russian fairytale Beautiful Vassilissa tells the story of a girls encounter with an ancient witch, which ends on a positive note. The German version, Frau Trude, ends on a negative note. If one scrutinizes both versions, then one sees that the girl in the Russian version is kind and obedient and has good common sense, whereas her counterpart in the German version is disobedient, impertinent, and cheeky. This permeates the whole context, and because of this, one cannot interpret both fairy tales in the same way, despite the fact that both stories circle around the same archetype of an encounter with the Great Mother.

In what follows, my efforts are aimed at interpreting only a few classical stories, or basic types of important fairy tale plots, as it were, in order to help clarify for the reader the Jungian method of interpretation, a method which I believe to be well substantiated. If, as a result, some readers feel motivated to try their hand at interpretation and have fun doing so, then the goal of this book will have been achieved.

MARIE-LOUISE VON FRANZ

Ksnacht, Switzerland

April 1995

Next page