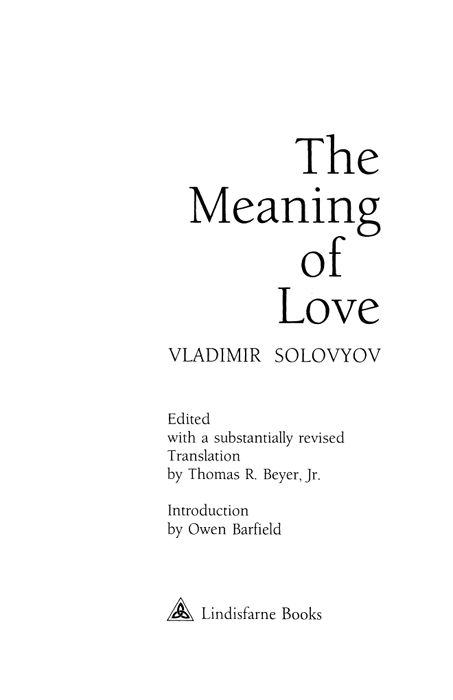

Vladimir Solovyov - The Meaning of Love

Here you can read online Vladimir Solovyov - The Meaning of Love full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1985, publisher: SteinerBooks, Incorporated, genre: Religion / Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Meaning of Love

- Author:

- Publisher:SteinerBooks, Incorporated

- Genre:

- Year:1985

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

The Meaning of Love: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Meaning of Love" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The meaning of human love, speaking generally, is the justification and salvation of individuality through the sacrifice of egoism. On this general basis we can also ... explain the meaning of sexual love (Vladimir Solovyov) What is the meaning of loves intense emotion? Solovyov points to the spark of divinity that we see in another human being and shows how this living ideal of Divine love, antecedent to our love, contains in itself the secret of the idealization of our love.

According to Solovyov, love between men and women has a key role to play in the mystical transfiguration of the world. Love, which allows one person to find unconditional completion in another, becomes an evolutionary strategy for overcoming cosmic disintegration.--------------hough it only began to flourish in the nineteenth century, Russian philosophy has deep roots going back to the acceptance of Christianity by the Russian people in 988 and the subsequent translation into the church Slavonic of the Greek Fathers. By the fourteenth century, religious writings such as those of Dionysius the Areopagite and Maximus the Confessor were available in monasteries. Until the seventeenth century then, except for some heterodox Jewish and Roman Catholic tendencies, Russian thinking tended to continue the ascetic, theological, and philosophical tradition of Byzantium, but with a Russian emphasis on the worlds unity, wholeness, and transfiguration. It was as if a seed were germinating in darkness, for the centuries of Tartar domination and the isolationism of the Moscow state kept Russian thought apart from the onward movement of Western European thinking. With Peter the Great (1672-1725), in Pushkins phrase, a window was cut into Europe. This opened the way to Voltairian freethinking, while the striving to find ever greater depths in religious life continued. Freemasonry established itself in Russia, inaugurating a spiritual stream outside the church. Masons sought a deepening of the inner life, together with ideals of moral development and active love of ones neighbor. They drew on wisdom where they found it and were ecumenical in their sources. Thomas Kempiss Imitation of Christ was translated, as were works by Saint-Martin (The Unknown Philosopher), Jacob Boehme, and the pietist Johann Arndt. Russian thinkers, too, became known by name: among others, Grigory Skovoroda (17221794), whose biblical interpretation drew upon Neoplatonism, Philo, and the German mystics; N.I. Novikov (1744-1818), who edited Masonic periodicals and organized libraries; the German I.G. Schwarz (1751-1784), a Rosicrucian follower of Jacob Boehme; and A.N. Radishchev (1749-1802), author of On Man and His Immortality. There followed a period of enthusiasm for German idealism, and with the reaction to this by the Slavophiles Ivan Kireevsky and Alexei Khomyakov, independent philosophical thought in Russia was bom. An important and still continuing tradition of creative thinking was initiated, giving rise to a whole galaxy of nineteenth- and twentieth-century philosophers, including Pavel Yurkevitch, Nikolai Fedorov, Vladimir Solovyov, Leo Shestov, the Princes S. and E. Trubetskoy, Pavel Florensky, Sergius Bulgakov, Nikolai Berdyaev, Dmitri Merezhkovsky, Vassili Rozanov, Semon Frank, the personalists, the intuitionists, and many others. Beginning in the 1840s, a vital tradition of philosophy entered the world stage, a tradition filled with as-yet unthought possibilities and implications, not only for Russia herself but for the new multicultural, global reality humanity as a whole is now entering. Characteristic features of this tradition are: epistemological realism; integral knowledge (knowledge as an organic, all-embracing unity that includes sensuous, intellectual, and mystical intuition); the celebration of integral personality (tselnaya lichnost), which is at once mystical, rational, and sensuous; and an emphasis upon the resurrection or transformability of the flesh. In a word, Russian philosophers sought a theory of the world as a whole, including its transformation. Russian philosophy is simultaneously religious and psychological, ontological and cosmological. Filled with remarkably imaginative thinking about our global future, it joins speculative metaphysics, depth psychology, ethics, aesthetics, mysticism, and science with a profound appreciation of the worlds movement toward a greater state. It is bolshaya, big, as philosophy should be. It is broad and individualistic, bearing within it many different perspectivesreligious, metaphysical, erotic, social, and apocalyptic. Above all, it is universal. The principle of sobornost, or all-togetherness (human catholicity), is of paramount importance in it. And it is future-oriented, expressing a philosophy of history passing into metahistory, the life-of-the-world-to-come in the Kingdom of God. At present, in both Russia and the West, there is a revival of interest in Russian philosophy, partly in response to the reductionisms implicit in materialism, atheism, analytic philosophy, deconstructionism, and so forth. On May 14th in 1988, Pravda announced that it would publish the works of Solovyov, Trubetskoy, Semon Frank, Shestov, Florensky, Lossky, Bulgakov, Berdyaev, Alexsandr Bogdanov, Rozanov, and Fedorov. According to the announcement, thirty-five to forty volumes were to be published. This is now taking place.The Esalen Institute-Lindisfame Press Library of Russian Philosophy parallels this Russian effort. Since 1980 the Esalen Russian-American Exchange Center has worked to develop innovative approaches to Russian-American cooperation, sponsoring nongovernmental dialogue and citizen exchange as a complement to governmental diplomacy. As part of its program, seminars are conducted on economic, political, moral, and religious philosophy. The Exchange Center aims to stimulate philosophic renewal in both the East and West. The Esalen-Lindisfame Library of Russian Philosophy continues this process, expanding it to a broader American audience. It is our feeling that these Russian thinkersand those who even now are following in their footstepsare world thinkers. Publishing them will not only contribute to our understanding of the Russian people but will also make a lasting contribution to the multicultural philosophical synthesis required by humanity around the globe as we enter the twenty-first century.

Vladimir Solovyov: author's other books

Who wrote The Meaning of Love? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.