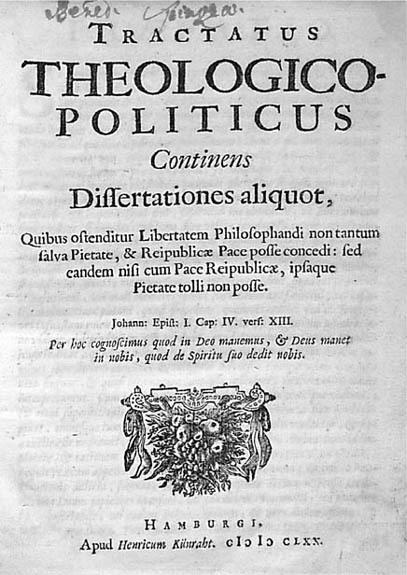

The title page of Spinozas Tractatus Theologico-Politicus , 1670; photograph courtesy of the Rare Books Division; Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library

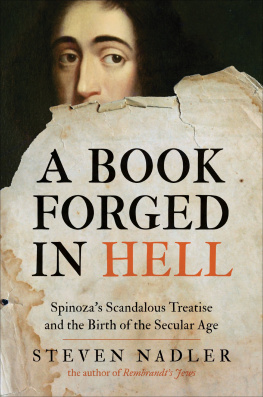

A Book Forged in Hell

Spinozas Scandalous Treatise and the Birth of the Secular Age

Steven Nadler

Copyright 2011 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock,

Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

Jacket art: Benedict Spinoza (163277), (oil on canvas) by Dutch School, Herzog August

Bibliothek, Wolfenbuttel, Germany / The Bridgeman Art Library

Jacket illustration: courtesy of Shutterstock

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Nadler, Steven M., 1958

A book forged in hell : Spinozas scandalous treatise and the birth of the secular age / Steven Nadler.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. 267) and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-13989-0 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Spinoza, Benedictus de, 16321677. Tractatus theologico-politicus. 2. Philosophy and religion. 3. Religion and politics. I. Title.

| B3985.Z7N34 2011 |

| 199.492dc22 | 2011005960 |

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Garamond 3

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Larry Shapiro

amicus currens optimus

The vilest hypocrites, urged on by that same fury which they call zeal for Gods law, have everywhere prosecuted men whose blameless character and distinguished qualities have excited the hostility of the masses, publicly denouncing their beliefs and inflaming the savage crowds anger against them. And this shameless license, sheltering under the cloak of religion, is not easy to suppress.

Baruch Spinoza, Theological-Political Treatise

Contents

Preface

Writing in May 1670, the German theologian Jacob Thomasius fulminated against a recent, anonymously published book. It was, he claimed, a godless document that should be immediately banned in all countries. His Dutch colleague, Regnier Mansveld, a professor at the University of Utrecht, insisted that the new publication was harmful to all religions and ought to be buried forever in an eternal oblivion. Willem van Blijenburgh, a philosophically inclined Dutch merchant, wrote that this atheistic book is full of abominations... which every reasonable person should find abhorrent. One disturbed critic went so far as to call it a book forged in hell, written by the devil himself.

The object of all this attention was a work titled Tractatus Theologico-Politicus ( Theological-Political Treatise ) and its author, an excommunicated Jew from Amsterdam: Baruch de Spinoza. The Treatise was regarded by Spinozas contemporaries as the most dangerous book ever published. In their eyes, it threatened to undermine religious faith, social and political harmony, and even everyday morality. They believed that the authorand his identity was not a secret for very longwas a religious subversive and political radical who sought to spread atheism and libertinism throughout Christendom. The uproar over the Treatise is, without question, one of the most significant events in European intellectual history, occurring as it did at the dawn of the Enlightenment. While the book laid the groundwork for subsequent liberal, secular, and democratic thinking, the debate over it also exposed deep tensions in a world that had seemingly recovered from over a century of brutal religious warfare.

The Treatise is also one of the most important books of Western thought ever written. Spinoza was the first to argue that the Bible is not literally the word of God but rather a work of human literature; that true religion has nothing to do with theology, liturgical ceremonies, or sectarian dogma but consists only in a simple moral rule: love your neighbor; and that ecclesiastic authorities should have no role whatsoever in the governance of a modern state. He also insisted that divine providence is nothing but the laws of nature, that miracles (understood as violations of the natural order of things) are impossible and belief in them is only an expression of our ignorance of the true causes of phenomena, and that the prophets of the Old Testament were simply ordinary individuals who, while ethically superior, happened also to have particularly vivid imaginations. The books political chapters present as eloquent a plea for toleration (especially the freedom to philosophize without interference from the authorities) and democracy as has ever been penned.

The reputation of a philosopher from the past is often at the mercy of what is popular among contemporary practitioners. The canon of classical philosophers, while relatively stable at its core for a long time (like the permanent members of the United Nations Security Council), has seen its share of additions and dismissals. And for a long time, especially in the Anglo-American philosophical world in the first half of the twentieth century, Spinoza did not make the cut. While he may have continued to enjoy honorary status as one of the great Western thinkers, he was not considered to be a relevant one, and his works were rarely studied even in survey courses in the history of philosophy. It certainly did not help that his metaphysical-moral magnum opus, the Ethics , while composed in the geometric style, was extremely opaque (contrary to the clarity of thinking and writing prized, at least in principle, by analytic philosophers), and that in that work he propounded doctrines that seemed to many to border on the mystical.

Spinozas rehabilitation in the latter half of the twentieth century progressed as metaphysics and epistemology came to dominate academic philosophy. The metaphysics in fashion was not the system-building kind of earlier periods, including that of Spinoza or the idealist sort favored by the latter-day Hegelians of Cambridge in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but rather precise analytic investigations into mind, matter, causation, and universals. Meanwhile, modern epistemologists, like Plato and Descartes before them, inquired into the nature of belief, truth, justification, and knowledge. And these were all topics on which, it was believed, Spinoza (despite his grander pretensions) had something interesting and relevant to say. Moreover, his unorthodox view of God and his ingenious approach to the mind-body problem made him seem, in some respects, much more modern than his more religiously inclined seventeenth-century contemporaries.

The somewhat problematic result of this was that Spinoza (again, like Descartes) came to be seen as someone who was primarily engaged in metaphysics and epistemology, and who was interested only in such questions as the nature of substance and the mind-body problem and in addressing the skeptical challenges to human knowledge. The focus, in teaching and in scholarship, was on the first two parts of the Ethics , in which are found Spinozas monistic view of nature, his account of understanding and will, and the mind-body parallelism that is supposed to be his response to the difficulties faced by Descartess dualism. Parts Three, Four, and Five of the Ethics his theory of the passions and his moral philosophywere seldom discussed at all (and even less frequently taught). This produced a very incomplete and misleading picture of Spinozas philosophical project; one was left wondering why the work is called Ethics .