Virtus Romana

STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF GREECE AND ROME

Robin Osborne, James Rives, and Richard J. A. Talbert, editors

Books in this series examine the history and society of Greece and Rome from approximately 1000 B.C. to A.D. 600. The series includes interdisciplinary studies, works that introduce new areas for investigation, and original syntheses and reinterpretations.

CATALINA BALMACEDA

Virtus Romana

Politics and Morality in the Roman Historians

The University of North Carolina Press Chapel Hill

2017 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Set in Arno Pro by Westchester Publishing Services

Manufactured in the United States of America

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Balmaceda, Catalina, 1970- author.

Title: Virtus romana : politics and morality in the Roman historians / Catalina Balmaceda.

Other titles: Studies in the history of Greece and Rome.

Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press,

[2017]

| Series: Studies in the history of Greece and Rome | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017007235| ISBN 9781469635125 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469635132 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: RomeHistoriography. | National characteristics, Roman. | RomeCivilization.

Classification: LCC DG205 .B33 2017 | DDC 937/.02dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017007235

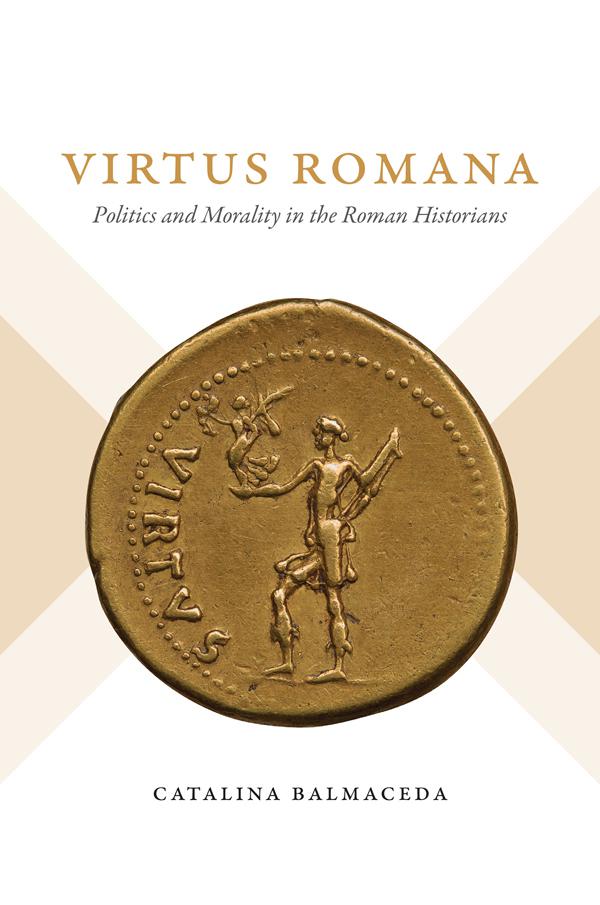

Cover illustration: Reverse side of Roman gold coin featuring Virtus, wearing tunic and cuirass, standing left, holding Victory on globe in right hand and parazonium in left. The Trustees of the British Museum.

Parentibus optimis

Contents

Illustrations

Acknowledgments

The completion of this book has taken several years and gives me at last the pleasure of thanking the many friends and scholars who have helped me along the way. First, I would like to thank Michael Comber, whose expert guidance and brilliant teaching opened up new ways of thinking and showed me many unexpected approaches to history; his friendship and patience were constant sources of support at a time when this project was not even conceived. I think he would have liked to see this book. I am also grateful for many inspiring and thought-provoking conversations with Valentina Arena, Rhiannon Ash, Catharine Edwards, Georgy Kantor, John Marincola, Michael Peachin, Chris Pelling, Francisco Pina Polo, Nicholas Purcell, Tobias Reinhardt, Malcolm Schofield, and Felipe Soza: all of them have greatly helped me with their general comments as well as their specific suggestions. Special thanks to Teresa Morgan, who read several draft chapters and gave me relevant feedback by challenging the whole structure of the book, which forced me to look for strategies and ways of presenting my argument more strongly. Miriam Griffin has been extremely generous in helping me throughout and especially on the philosophical aspects of this book: pointing out the weaknesses, and at the same time guiding me in the right direction. I also owe a great debt to Fergus Millar, whose constant support and wise advice have not failed me since my first day in Oxford, many years ago. My friend Henriette van der Blom, who has been involved in this project from the very beginning, has been always willing to share her time talking things over with unfailing reassurance. I am endlessly grateful to Katherine Clarke, who has been key at all stages of my work. Her ever-encouraging and enthusiastic approach to the project, together with her attention to small details and their relation to the broader issues, helped me enormously in the development of this book.

I have been also privileged to have the comments and constructive criticisms from the audiences of different lectures, seminars, and conference papers given at Santiago, Rome, Leicester, Via del Mar, London, Oxford, and So Paulo.

During the years that I spent writing this book, I benefited from several grants. I was a British Academy Visiting Fellow (200910), recipient of the Fondecyt Research Council Award (201012) and Wolfson Visiting Scholar (201314). I am grateful for the opportunities these grants gave me to expand my study time and to meet and discuss with important scholars related to my line of research. I am particularly grateful to my home institution, Pontificia Universidad Catlica de Chile, which allowed me the time necessary to develop this work and supported me financially and academically at every stage.

I would like to thank the expert hand of Helena Scott, everyone on the editorial team at the University of North Carolina Press, and the anonymous readers for their professional and helpful advice throughout the process.

My family and friends have kept my courage up and contributed greatly to make the ups and downs proper to any research project of this magnitude into a vast majority of ups, and I am grateful for their patience and generosity, especially for Maureens constant support and Anas cheerful friendship. It is to my parents, though, that I owe the greatest debt, and therefore this book is dedicated to them.

Catalina Balmaceda

November 2016

Abbreviations in the Text

References to ancient authors and texts follow the conventions of the Oxford Classical Dictionary , 4th edition.

Abbreviations of periodicals follow the conventions of LAnne Philologique . In addition, the following abbreviations have been adopted:

ANRW

Aufstieg und Niedergang der rmischen Welt. Geschichte und Kultur Roms im Spiegel der neueren Forschung . Berlin, 1972.

CAH

The Cambridge Ancient History , 2nd edition. Cambridge, 1994.

CIL

Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum . Berlin.

FrHist

The Fragments of the Roman Historians , vols. 13. Edited by T. Cornell. Oxford, 2013.

ILS

Inscriptiones Latinae Selectae . H. Dessau. Berlin, 1892.

ORF

Oratorum Romanorum Fragmenta , 3rd edition. Edited by E. Malcovati. Turin, 1967.

RIC

Roman Imperial Coinage . Vol. 1, AugustusVitellius (31 B.C.69 A.D.) . C. H. V. Sutherland. London, 1923 (revised 1984).

Unless otherwise indicated, all translations are my own or from the latest Loeb editions, adapted where necessary.

Introduction

Virtus and Historical Writing

Virtus propria est Romani generis et seminis

Virtus is an inalienable possession of the Roman race and name

Cic. Phil , 4.13

In recent years, it has proved fruitful to approach the history of Roman politics, society, and culture thematically, through the study of key concepts such as fides , libertas , clementia , or pudicitia . Among such concepts, none was more important to Romans themselves than virtus . Virtus could be found everywhere and under any circumstance: it was what everybody claimed, an aim for life, a means to achieve gloria , a criterion by which to judge people, a spur to action, the courage to undertake brave deeds, the essence of manliness, the moral code of the maiores For the Romans it was difficult to approach any important topic without referring to virtus .

As a moral and political idea, however, virtus was present in Roman thinking and acting in many more ways than have been explored hitherto. Past approaches to virtus have tended to be word studies. Of particular note is the work of A. N. van Omme, Virtus, semantiese Studie (Utrecht, 1946), which was later completed and enriched by the book of W. Eisenhut, Virtus Romana: Ihre Stellung im rmische Wertsystem (Munich, 1973). Eisenhuts work is an impressive lexicographical exercise; he traces almost every occurrence of virtus in classical Latin, but the conclusions are limited and unduly biased toward the view that Greek culture played an essential role in the formation of the concept. Additionally, Eisenhut argues that the different kinds of virtus remained fairly stable throughout Roman history.