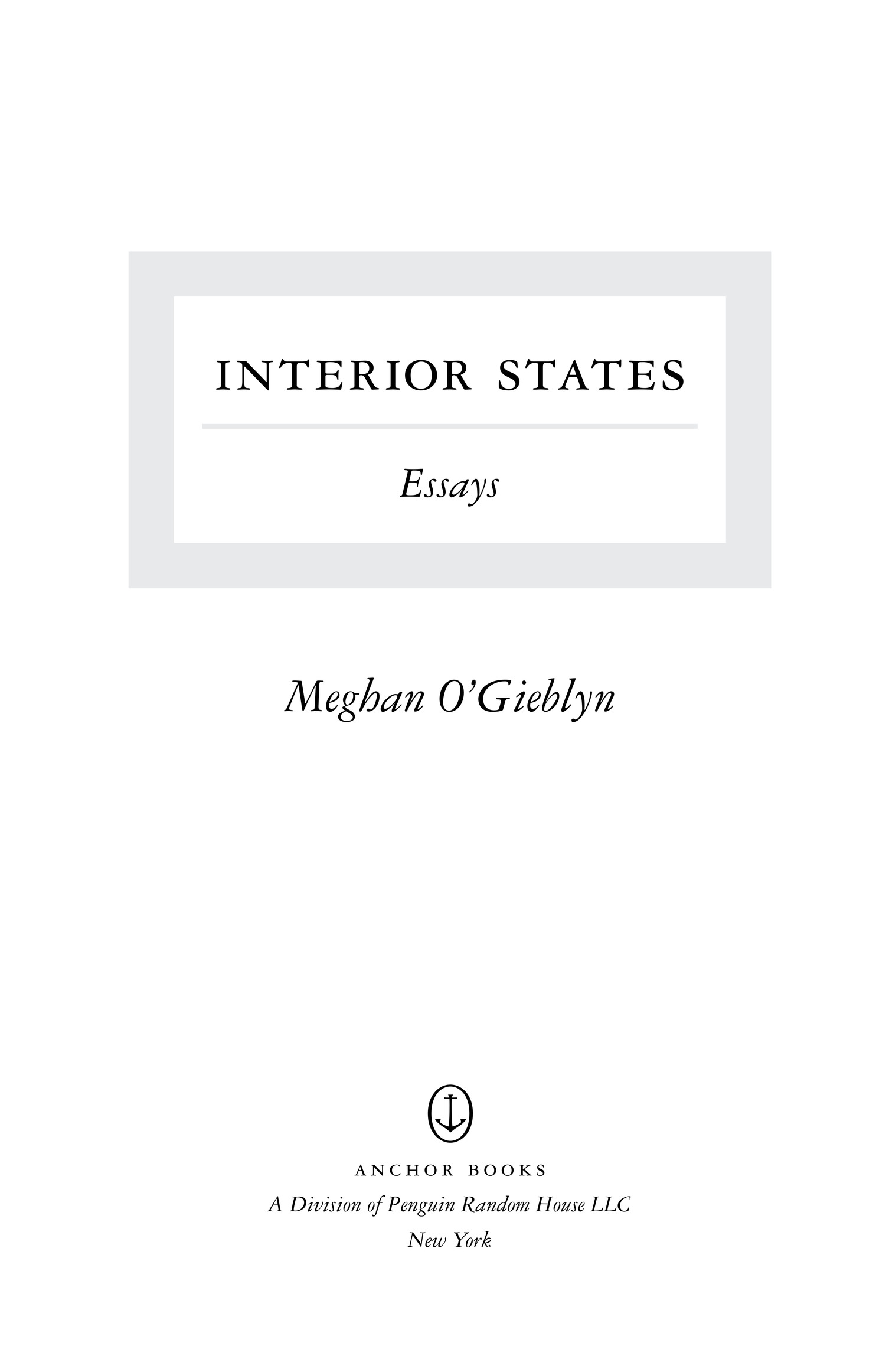

Meghan OGieblyn

INTERIOR STATES

Meghan OGieblyn is a writer who was raised and still lives in the Midwest. Her essays have appeared in Harpers Magazine, n+1, The Point, The New York Times, The Guardian, The New Yorker, Best American Essays 2017, and the Pushcart Prize anthology. She received a BA in English from Loyola University Chicago and an MFA in Fiction from the University of WisconsinMadison. She lives in Madison, Wisconsin, with her husband.

www.meghanogieblyn.com

AN ANCHOR BOOKS ORIGINAL, OCTOBER 2018

Copyright 2018 by Meghan OGieblyn

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Anchor Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

Anchor Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Several pieces first appeared in the following publications: Pure Michigan on The Awl; The End in the Boston Review; Sniffing Glue in Guernica; Exiled in Harpers Magazine; Maternal Ecstasies and On Reading Updike in The Los Angeles Review of Books; Ghost in the Cloud in n+1; American Niceness in The New Yorker; A Species of Origins in Oxford American; Contemporaries in Ploughshares; Hell, The Insane Idea, and Midwestworld in The Point; Dispatch from Flyover Country in The Threepenny Review; and On Subtlety in Tin House.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: OGieblyn, Meghan, 1982 author.

Title: Interior states : essays / by Meghan OGieblyn.

Description: First edition. | New York : Anchor Books, [2018]

Identifiers: LCCN 2018004173 (print) | LCCN 2018004981 (ebook)

Classification: LCC PS 3615. G 54 (ebook) | LCC PS 3615. G 54 A 6 2018 (print) | DDC 814/.6dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018004173

Anchor Books Trade Paperback ISBN9780525562702

Ebook ISBN9780385543842

Cover design by Perry De La Vega

www.anchorbooks.com

v5.3.2

ep

All Americans come from Ohio originally, if only briefly.

DAWN POWELL

The Middle West is probably a fanatic state of mind. It is, as I see it, an unknown geographic terrain, an amorphous substance, the ghostly interplay of time with space, the cosmic, the psychic, as near to the North Pole as to the Gallup Poll.

MARGUERITE YOUNG

Contents

PREFACE

One criticism of the personal essayan old one, though its been revived with special fervor in recent yearsis its tendency toward confession. To some extent, this is simply a matter of lineage. The origins of what we today call personal writing can be traced back to Augustine, so its not coincidental that the genre so frequently reverts to the tenor of the Christian ritual: the divulging of transgressions, the preening need for absolution. In fact, Ive often sensed in these complaints about confessional writing an underlying impatience with religion itself and the persistence of its postures in modern life. It is now the twenty-first century, these critics seem to say, and high time we got off our knees and took ownership of our lives.

The faith tradition in which I was raised, evangelical Protestantism, did not practice the rite of private confession. We did not confess; we professed, and we did so publicly. The narrative ritual taken up by our congregation was performed in front of the entire body of fellow believers, a convention called giving testimony. Most often, your testimony was your life story, though it could also be about a particular struggle or a period of doubt. While confession is typically born of guilt and predicated upon the experience of private catharsis, the testimony had a decidedly communal purpose. The point was not to absolve oneself, but rather to testify to the truth of the gospel, using ones story as a form of evidence. Like the courtroom practice from which it derived its name, the idea was that your personal experience was a way of building a case.

Each of the pieces collected in this volume is, in some sense, a testimony, which is to say the essays were spurred not by the need to unburden myself, but rather to connect my experiences to larger conversations and debates. Not all of these essays contain an explicit argument, but each began with a desire to make a claimor in some cases, to complicate an existing onecoupled with the feeling that my life might serve as a form of evidence. The earliest ones were composed when I was still contending with my loss of faith, and writing them was a way to impose some semblance of order on a world that felt muddled and morally chaotic. Although these early pieces were published in secular magazines, I was writing primarily to evangelicals, trying to elucidate what I saw as a central hypocrisy of the faith I had left: namely, the churchs willingnessin its theology on hell, its relationship to science, and its approach to youth cultureto compromise its doctrine in order to remain culturally relevant.

Over the past decade, most of the writing on Christianity in this country has taken the form of obituary. More than one of the magazine editors who published these essays insisted that I acknowledge the 2014 Pew Research study about the rise of the nonesyoung people who claim no religious affiliationas though to affirm the popular notion that America is leaving behind its superstitious past and treading unwaveringly into the future. Perhaps this is true. But as someone who has traveled that path myself, I can confirm that such journeys are rarely linear or without complications. William James once noted that the most violent revolutions in an individuals beliefs leave most of his old order standing. In other words, even when a person outwardly denounces a long-standing belief, the architecture of the idea persists and can come to be inhabited by other things. This is as true of cultures as it is of individuals. Some of the essays in this collection examine the ways in which our increasingly secular landscape is still imprinted with the legacy of Christianity. The testimony, as a narrative form, endures in the rooms of twelve-step programs and in contemporary writing about motherhood, which often takes the form of conversion narrative. Meanwhile, the faiths epic story of messianic redemption lives on in the utopic visions of transhumanism and in liberalisms endless arc of progress.

Many of these essays return to questions about history and historical narratives. It is a topic that is difficult these days to avoidthough this is particularly true for those of us who live in the Midwest, which F. Scott Fitzgerald famously called, in The Great Gatsby, the ragged edge of the universe, a place where its easy to conclude that history is over. Much of my childhood took place outside Detroit, a city that was, during those years, in the process of being reclaimed by the prairie, its downtown haunted by six empty prewar skyscrapers. During the bleakest years of the financial crisis, these rotting cathedrals of commerce became such an unambiguous symbol that some residents proposed their ruins should be preserved as an urban Monument Valley that tourists could visit, as they do the Acropolis of Athens, to witness the collapse of American empire. Of course, this never transpired. Instead, this stretch of downtown has been transformed into a playground for the creative class, a development that has displaced the citys most vulnerable residents and only heightened the sense of historic unreality. Like so many metropolises along the Rust Belt, Detroit has become a hastily drawn caricature of the city it once was, festooned with the signifiers of the manufacturing age (Diego Rivera murals, PBR on tap) that have been drained of any real political and economic significance, while its factories have been reimagined as farm-to-table restaurants and the sleek offices of tech start-ups.