Henricus Institoris - The Hammer of Witches

Here you can read online Henricus Institoris - The Hammer of Witches full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 0, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Hammer of Witches

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:0

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Hammer of Witches: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Hammer of Witches" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Hammer of Witches — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Hammer of Witches" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

THE HAMMER OF WITCHES

A complete Translation of theMalleus Maleficarum

CHRISTOPHERS. MACKAY

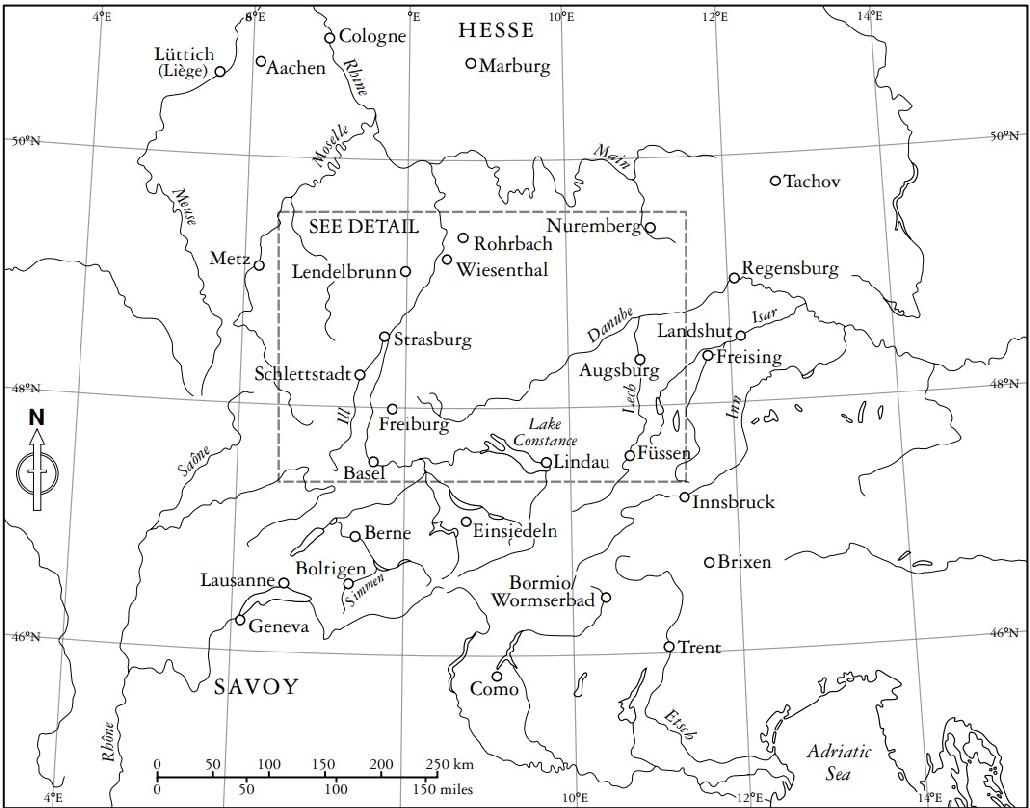

MAP 1

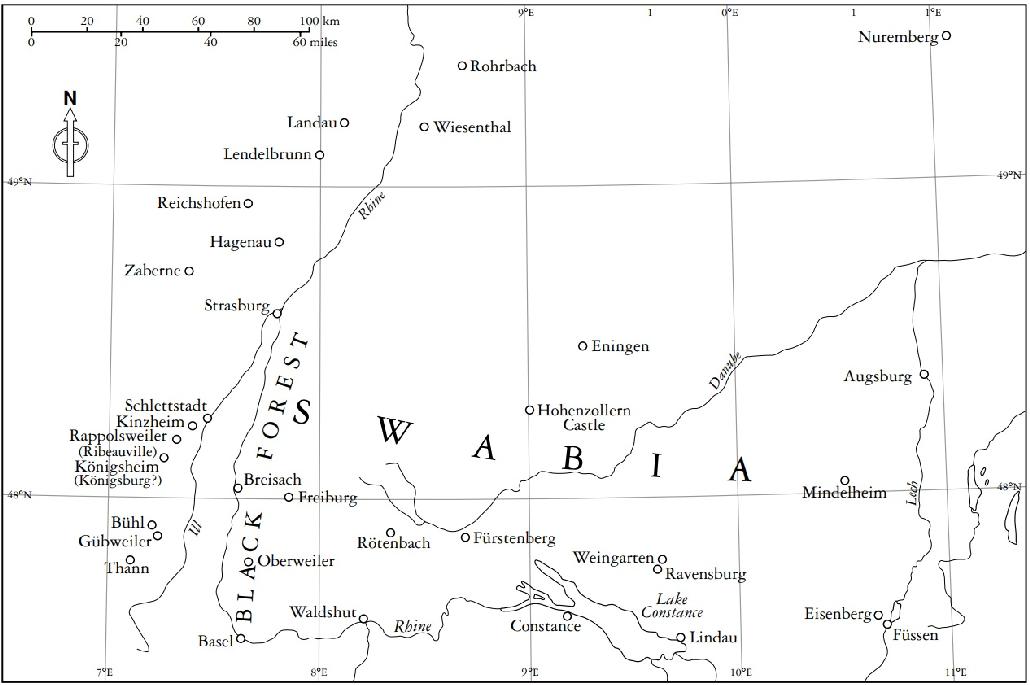

MAP 2

The Malleus Maleficarum , first published in 1486, is the standard medieval text on witchcraft and it remained in print throughout the early modern period. Its descriptions of the evil acts of witches and the ways to exterminate them continue to contribute to our knowledge of early modern law, religion and society. Mackays highly acclaimed translation, based on his extensive research and detailed analysis of the Latin text, is the only complete English version available, and the most reliable. Now available in a single volume, this key text is at last accessible to students and scholars of medieval history and literature. With detailed explanatory notes and a guide to further reading, this volume offers a unique insight into the fifteenth-century mind and its sense of sin, punishment and retribution.

CHRISTOPHER S. MACKAY is Professor in the Department of History and Classics at the University of Alberta. He is the author of, among many books and articles, Ancient Rome: A Military and Political History (Cambridge University Press, 2005).

Kelliae meae

Coniugi atque adiutrici

optimae

The Malleus Maleficarum is undoubtedly the best known (many would say most notorious) treatise on witchcraft from the early modern period. Published in 1486 (only a generation after the introduction of printing by moveable type in Western Europe), the work served to popularize the new conception of magic and witchcraft that is known in modern scholarship as satanism or diabolism, and it thereby played a major role in the savage efforts undertaken to stamp out witchcraft in Western Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (a series of events sometimes known as the witch craze). The present work offers the reader the only full and reliable translation of the Malleus into English, and this introduction has a very specific purpose: to set out for the reader the general intellectual and cultural background of the Malleus, which takes for granted and is based upon a number of concepts that are by no means self-evident to the average modern reader, and to explain something of the circumstances of the works composition and the authors methods and purposes in writing it. That is, the aim here is the very restricted one of giving the reader a better insight into how the work would have been understood at the time of its publication. Hopefully, this will help not only those who wish to understand the work in its own right but also those who are interested in the later effects of this influential work.

At the outset, a word about terminology. As is explained later (see below in section e of the Notes on the translation), for technical reasons relating to the Latin text, male and female practitioners of magic are called sorcerers and sorceresses respectively in the translation, and the term for their practices is sorcery. In the preceding paragraph, the term witchcraft was used, but this term comes with a lot of unwelcome modern baggage that can only serve to confuse the strictly historical discussion that follows. Accordingly, sorceress and sorcery will henceforth be used in place of witch and witchcraft to emphasize the point that what we are dealing with are the notions that were held about magic and its practitioners in the late medieval and early modern periods.

In view of the intended audience, the material here is largely laid out very briefly as a straightforward discussion without elaborate footnotes or citation of relevant authorities. Apart from the further reading given at the end, the reader who wishes to learn more detail about the various topics or to find out specific citations of sources is directed to the far more elaborate General Introduction to be found in volume I of my bilingual edition entitled Malleus Maleficarum (Cambridge University Press, 2006).

According to the Authors Justification of the Malleus , there were two authors Jacobus Sprenger and an unnamed collaborator whose respective roles in the composition of it are not specified. In the public declaration that constitutes the Approbation of the work, Henricus Institoris indicates that he and his colleague as inquisitor, Jacobus Sprenger, wrote the Malleus . There is some dispute about this joint authorship in modern scholarship, but, before turning to this, we should look at what is known of these two men.

As both men were Dominican friars, a few words about this institution may be helpful. The Order of Preachers (the official name of the order) was founded in the early thirteenth century to combat heresy. Though Dominicans took the same sort of vows of poverty as monks, these friars did not withdraw from the secular world by joining a monastery, but lived in society as part of their mission to root out heresy and enforce orthodoxy among the laity. Since the Order was intended to subvert heretical opposition to Church teachings, the Dominicans soon became involved in theological studies in order to sharpen their skills in spotting and rebutting heretical views. Hence, there was often a close connection between the local Dominican convent and the theological faculty at a neighboring university. These skills made it natural for the papacy to appoint Dominicans as inquisitors into heretical depravity.

Jacobus (the Latinized form of Jacob) Sprenger was born in about 1437, and presumably came from the area of Basel, as he is first attested joining the Dominican convent in that city in 1452. He went on to become an important figure in the Dominican Order, and was mostly associated with the convent of Cologne and the university of that city. Sprenger eventually became a professor of theology, serving as an administrator in both the theological faculty and the university as a whole. Sprenger was also interested in practical piety. He actively promoted the reform movement within the Order, which advocated a return to a simpler way of life among the residents of Dominican convents, and he was assigned the task of imposing reform in a number of these, even in the face of opposition from the residents. Sprenger would have been most famous in his lifetime for playing a prominent role in the spread of the practice of reciting the Rosary. Though he was appointed as an inquisitor in the Rhineland in 1481, there is no evidence for any active participation in this activity on his part (he is attested as being consulted in a few cases). Sprenger also showed little inclination for writing. Apart from an unpublished theological commentary written in connection with his early academic studies, his only composition was a short work about the society he founded to promote the Rosary. He died in 1495.

Henricus Institoris (the Latinized form of the German name Heinrich Kramer) was born around 1430 in the Alsatian town of Schlettstadt (modern Slstat). He joined the local Dominican convent, but went on to be attached to a number of other convents in the southern German-speaking lands. Like Sprenger, he became a professor of theology, but unlike Sprenger he did not pursue an academic career. Instead, Institoris was more interested in missions among the laity, and he tended to work on his own. He was deeply involved in the sale of indulgences, and in particular he undertook a number of tasks connected with the defense of papal privileges and the enforcement of orthodoxy. He spent his last years combatting the Hussite heresy in Bohemia, where he died in 1505.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Hammer of Witches»

Look at similar books to The Hammer of Witches. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Hammer of Witches and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.