For my mother

what can we bequeath

save our deposd bodies to the ground?

RICHARD II, III , 2

Preface

PHILIPPE MENNECIER, THE DIRECTOR OF CONSERVATION AT the Muse de lhomme, the great anthropology museum in Paris, is a tall, narrow man, thin of hair, with wire-rimmed glasses and the aspect of a bird of prey. Suitably enough, his office is something of an aerie, a low-ceilinged, rectangular box built as an afterthought on the roof of the museums headquarters, which you get to by climbing a portable metal staircase. Up here, he has surely one of the grandest workplace vistas on earth, taking in much of the Paris skyline. The view also gives a metaphorical frame to the work that Mennecier and his staff do: on one side, so close you cant get a full picture of it, is the Eiffel Tower, that nineteenth-century obelisk to reason and order; on the other is the Passy Cemetery, one of those wondrous Parisian cemeteries that, with their tangle of paths and tombs and high surrounding wall, resemble medieval cities in miniature, but ones populated by the dead rather than the living.

Death and order: that sums up the work that goes on here. The museum is not on the standard tourist itinerary, but its a place for which the French have a particular fondness. It was founded in the early nineteenth century, as part of the first burst of enthusiasm for the search for human origins, when explorer-scientistshale, moustachioed, fanatically dedicatedcombed the far reaches of the earth for anthropological specimens and human remains. Reflecting those origins, the museum has a retro feel. You might think of it as a temple devoted to the cult of evolution, which brings reason to bear on the conundrum of life and death by using bones to tell the modern story of who we are and how we got here. The cemetery below, meanwhile, with its mute stone crosses, gives another version.

Echoing the views and their bookended representations of reason and mortality, Menneciers office is cluttered with computer equipment and human remainsa tray randomly placed on a shelf neatly holds six human skulls, as if six were a standard set. But Mennecier is not himself an anthropologist but a linguist, as he made a point of noting when we first met. And what languages are his specialities? Esquimau et russe, he declaimed with a flourish: Eskimo and Russian. To properly appreciate this response you should know that it had already been established that he didnt speak English. What could be more exquisitely right for a French linguist than that he profess no working knowledge of the worlds dominant language but be one of the leading experts on the Eskimo dialect spoken exclusively in eastern Greenland and author of the only Tunumiisut-French grammar? On top of which, his pursuit of Inuit language variations around the earths northern reaches eventually led him to Siberia, so that he became fluent in Russian and now, as a sideline, translates contemporary Russian novels into French.

All of which is to say that Mennecier is a French intellectual. To many people in this age of universal dumbing down, that would be considered a slur, suggesting things like arrogance and a focus on narrow, cerebral, navel-gazing concerns. But the term can also encompass a way of looking at the world that is becoming sadly rarecall it a serious commitment to idiosyncrasy. People who are configured this way can give you a headache, but they can also delight you with their inexorable weirdness. They work the way a joke does, pulling you unexpectedly off the easy chair that is your customary vantage point. They make you remember, if only for a moment, what a wild place the world really is. So I was happy to ride this wave for the next few minutes, to listen to a little discourse on the seven Eskimo dialects, how they divide into two families, what linguistic markers separate them, and the efforts to preserve the dialects and their cultures.

Eventually, we clattered back down the metal staircase to the floor below. Here, two women in lab coats sat at a table handling human bones: long leg bones with porous, knobby joints; skulls of a slightly sickening orangey-brown hue. In the next room we passed a group of maybe four dozen complete human skeletons hanging on hooks, with a single gorilla skeleton standing in front of them like a short, thick sergeant drilling a lanky squadron. As we went back out through the entry to this area, we walked by a bust of Pierre-Paul Broca, the nineteenth-century anthropologist and pioneer of brain study. We headed downstairs, passing the main exhibition floor of the museum, with its quaint permanent exhibition, an almost aggressively confident display devoted to human evolution, in which a succession of dramatically lit dioramas hit the milestones in the march of bipedalism, from Australopithecus, with its wide arching plates of bone across the eyes, to Cro-Magnon, with its voluminous cranial capacity and frontal bulge, to their more delicate modern cousins.

Finally we could descend no further. The basement was in the process of being remodeled, and the fresh plasterwork and exposed bulbs gave it the pleasingly appropriate feel of a catacomb. My host produced a set of keys and opened a storage room door. Once we were inside, he unlocked a wall cabinet and pulled out a finely polished, curiously elegant wooden box whose lid was fastened with metal hasps. He unsnapped these; there was a flourish of gauzy white paper, then he reached in and extracted the object I had come to see.

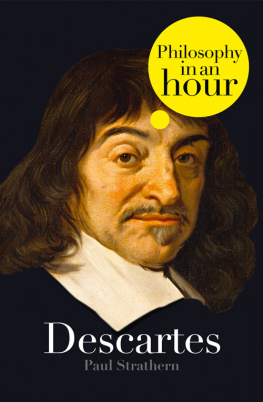

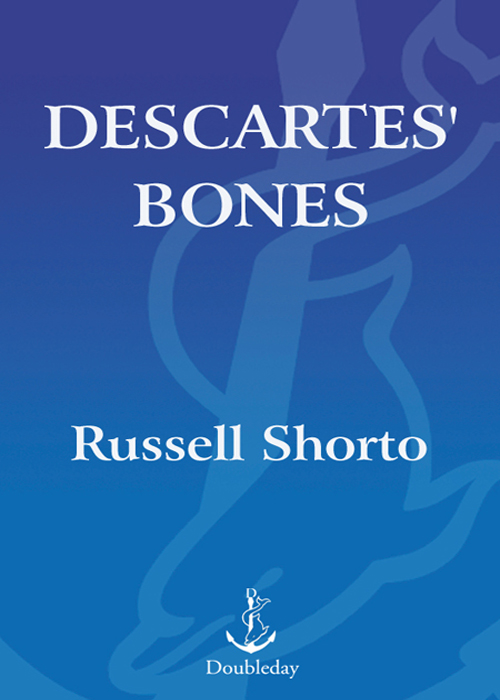

It was small, smooth, surprisingly light. The color varied: in places it had been rubbed to a pearly gloss while other areas were deeply grimed; but mostly it had the look of old parchment. And indeed, it was an object with stories to tell, not only figuratively but literally. More than two centuries ago someone had written a lofty poem in Latin on its crown, the letters of which were now faded to a watery brown. Another inscription, right across the forehead, hinted darklyand in Swedishof a theft. Tightly scrawled signatures of three of the men who had owned it through the ages were faintly visible on the sides. It was the skull of Ren Descartes, the so-called father of modern philosophy and one of the more consequential humans who ever lived. Mennecier set it on a table before me. Voil le philosophe, he said drily.

T HREE YEARS EARLIER, while sitting in the Main Reading Room of the New York Public Library plowing through a volume of seventeenth-century philosophy, I had chanced upon the fact that, sixteen years after his death in 1650, Descartes had suffered the indignity of having his bones dug up, after which people began taking pieces of his remains.

Why do certain thoughts stick in the mind? They seem to have no practical value but stand out from sheer strangeness. Typically youll entertain them for a while, like a childs toy found between sofa cushions, then forget them, uselessness having defeated novelty. Certainly this item about Descartes bones seemed a pristine example of a useless piece of information. And yet I fell in love with it, the way you can only fall in love with something truly odd that you find buried in a very old book. It has happened to me only a few times: you have the feeling, improbable but strong, of having uncovered a dormant seed, one that was planted in just that spot by someone now long dead who knew, or hoped, that one day you would find it, water it, and bring it to life.