for Luke, Melanie, and, of course, John Henry

Contents

A Brief Word to the Reader

on How the Book Was Made

and Who Helped Me Make It

I GIVE AN ACCOUNT OF the genesis of The Dark Side of the Enlightenment in the introduction, which also attempts to lay out its principal subject matter. A long-standing interest in the English and French literature of the eighteenth century led me to its chief subjects. The reading of any work of literature becomes richer and more intelligible when conducted against the background of the intellectual climate in which it was created, but for the period of the Enlightenment the historical background is often indispensable. First in preparing to write the book and then again while actually writing it, I spent several years pursuing such apparently disparate topics as alchemy, epistolary culture, Renaissance Egyptology, Jansenism, Pietism, the spread of Freemasonry in France, and the rise and decline of the literary salon . I say apparently disparate because one at length discovers in the period of the Enlightenment, as of course in other historical periods, some convincing overarching unities.

This book, though necessarily founded in a wide reading of scholarly literature over many years, is intended for the educated general reader rather than the specialist. Accordingly, I do not supply the footnote citations and extensive bibliography appropriate for the genre of the academic monograph. However, I have appended to each chapter a brief bibliography. It gives the details of works on which I have chiefly relied and identifies most from which I have actually quoted. Some of the sources appear in specialized journals found only in research libraries. In the hopes that The Dark Side may stimulate the readers interest in this or that aspect of its materials, I also offer some general suggestions for possible further reading. I have tried whenever possible to direct the reader to materials written in the English language or available in English translation. I have also tried to exercise an option for the readable. Inevitably the best sources on European topics and persons are sometimes written in European languages, and I cite such foreign-language scholarship as has significantly shaped my book.

With a few rare exceptions, such as perhaps St. John the Divine on the isle of Patmos, authors rarely really write books on their own. Certainly I could never have written this one without the help of many family members, friends, colleagues, and professional collaborators in the publishing business. I want to acknowledge some of them by name here:

Most of the preparation of this book was done in the Firestone Library of Princeton University, but I also enjoyed the facilities of the American Library in Paris. My first debt of gratitude, as always, is to the librarians who work so effectively to preserve and make accessible the materials of humanistic study. Without the stimulating conversations of many professional friends and colleagues over the decades I would never have undertaken the project. Stimulation in genesis is not the same thing as approbation in result, and my sincere gratitude for the former comes entirely without any spurious claim of the latter. My family, typified by the young scholars to whom I have dedicated the book, have tolerated my foibles and indulged my enthusiasms for a long time, in some instances for more than half a century. I am aware of my great good fortune.

I have been fortunate, too, in the professionals I have worked with in the publishing world. The cheerful optimism of my delightful literary agent, Julia Lord, is an unfailing tonic. At W. W. Norton I enjoyed once again the expert help of Starling Lawrence, this time aided by his young associate Ryan Harrington. If I think of them as the Batman and Robin of New York literary editors, Ann Adelman, my copy editor, is beyond question the Wonder Woman. My wife Joan and my friend Eli Schwartz shared with me the inglorious labors of proofreading. Thank you.

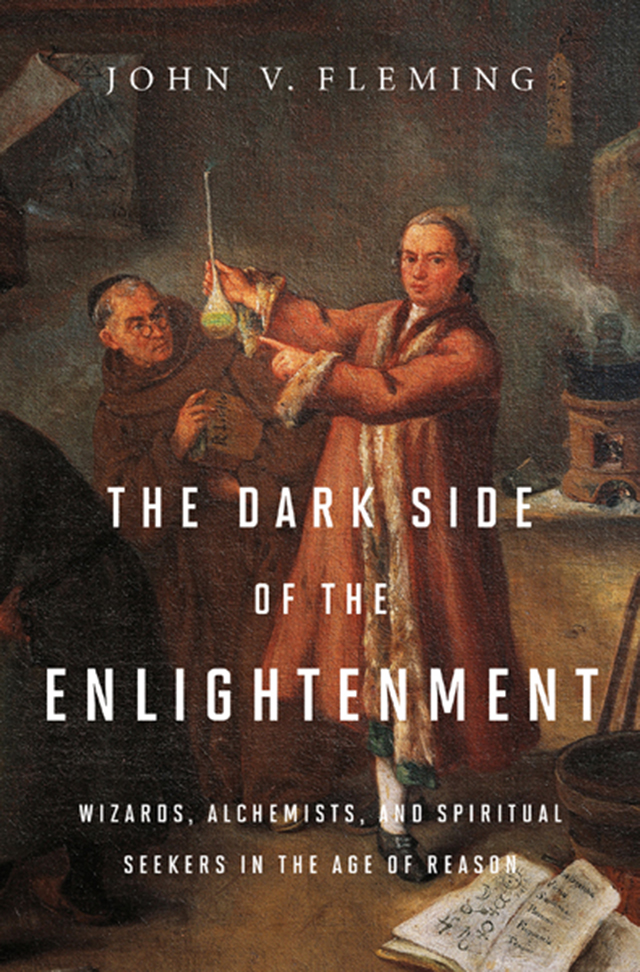

Introduction:

The Light and the Dark

T HE DARK SIDE OF THE ENLIGHTENMENT is a work of cultural and literary history. Its subjects include certain historical phenomena of the Enlightenment period (the awkward persistence of miracles, learned occultism, Rosicrucianism and Freemasonry, among them) and certain personages (Cagliostro and Julie de Krdener most prominently) presenting challenges to the generally held views of what the Enlightenment was, and what it did. My book does not pretend to present a sequential argument, let alone a new definition of Enlightenment or a fresh interpretation of it. It does, however, argue for a more capacious examination of what was enlightened.

One of the first things that strikes the interested reader who approaches the large literature of eighteenth-century intellectual history is that the very term Enlightenment as used by scholars is elastic if not protean. Thus we have political Enlightenment, radical Enlightenment, classical Enlightenment, scientific Enlightenment, and many more. We have local Enlightenments galore: the Scottish, the French, the Baltic, and the Bavarian. They are joined by Counter-Enlightenment, an anti-Enlightenment, enemies of Enlightenment.

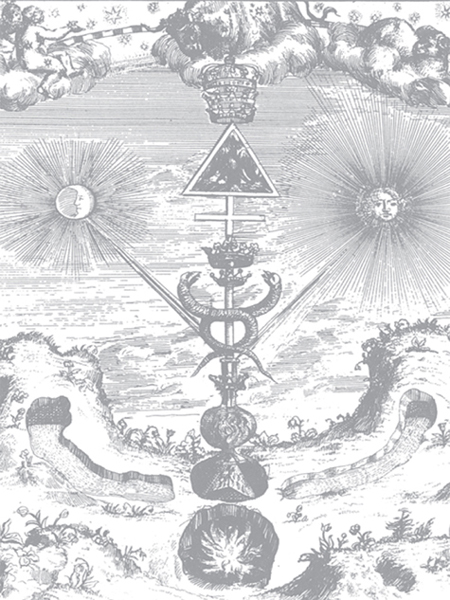

It is not going too far to say that many scholarly definitions of the Enlightenment have been designed in part to exclude important phenomena uncongenial to the definer. Thus historians of the Age of Reason have often taken a more restrictive definition of reason than did the thinkers and writers of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Henry Stubbe was, in his view, a scientist. His defense of the miracles wrought by Valentine Greatrakes was based in a rational and scientific mentality, though one of a different sort than that exhibited by some of his antagonists in the Royal Society. It was likewise an increasingly augmented and enlightened confidence in the power and potential of natural philosophy that encouraged the natural magicians and the alchemistsalchemy being, indeed, the Queen of Enlightenment Science.

Each of the chapters of this book deals with topics or personages enabled and defined by the Enlightenment context. Sorcerers had existed since the time of the Bible and before. But a sorcerer like Count Cagliostro was made possible only by an essentially new social context, the features of which included extensive and rapid international communication of ideas in a functioning Republic of Letters, and a self-conscious and well-organized international intellectual elite of Rosicrucians and Freemasons. There seems to me no good reason to divorce from the Enlightenment the focus on personal emotion and artistic sentiment of a Julie de Krdener. Romanticism was not always the rejection of Enlightenment, but oftenat least in the minds of the Romanticsits expansion and refinement. The origins of Romanticism are intimately connected with hermetic and occult traditions nurtured by an Enlightenment elite.

I CHOSE THE TITLE The Dark Side of the Enlightenment, which is meant to be good-humored as well as lighthearted, for probably obvious reasons. It seems rather catchy. It plays against the flattering idea of intellectual and spiritual illumination that gave birth to the word Enlightenment, as well as its principal European equivalents, the French Lumires and the German Aufklrung . Since the period of the Enlightenment witnessed, among other things, a remarkable efflorescence of occultism and mysticism, and since such topics occupy much of my attention, the title seemed to me not merely appropriate but inevitable. Only when I was well into my researches did I come across a German book (Thomas Frellers Cagliostro: Die dunkle Seite der Aufklrung, 2001) that anticipates it in its subtitle.

Next page