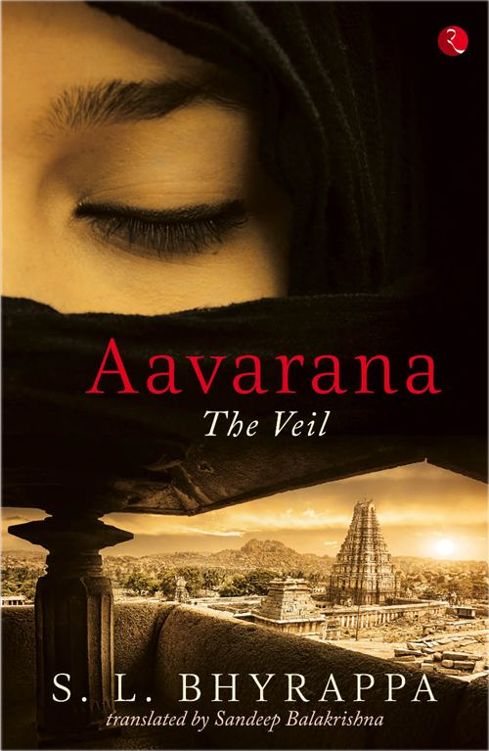

AAVARANA

Dr S.L. Bhyrappa is widely regarded as the greatest living novelist in Kannada. In a literary career spanning over fifty years he has authored twenty-two novels, which have been translated into most of the major Indian languages, including Urdu. His works have run into several reprints and have been the subject of numerous scholarly studies, as well as heated public debates. Of his books, Daatu won the Sahitya Akademi award while Mandra won him the prestigious Saraswati Samman. He lives in Mysore.

Sandeep Balakrishna is a writer, columnist, translator and recovering IT professional. He is the author of Tipu Sultan: The Tyrant of Mysore and is currently engaged in researching the history of the Vijayanagar Empire. Sandeep heads IndiaFacts, an online portal that aims to restore balance and factual accuracy in the media and public discourse.

Published by

Rupa Publications India Pvt. Ltd 2014

7/16, Ansari Road, Daryaganj

New Delhi 110002

Sales Centres:

Allahabad Bengaluru Chennai

Hyderabad Jaipur Kathmandu

Kolkata Mumbai

Copyright S.L. Bhyrappa 2014

Translation copyright Sandeep Balakrishna 2014

This is a work of fiction. All situations, incidents, dialogue and characters, with the exception of some well-known historical and public figures mentioned in this novel, are products of the authors imagination and are not to be construed as real. They are not intended to depict actual events or people or to change the entirely fictional nature of the work. In all other respects, any resemblance to persons living or dead is entirely coincidental.

eISBN: 9788129131966

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated, without the publishers prior consent, in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published.

PREFACE

The act of concealing truth is known as aavarana, and that of projecting untruth is called vikshepa. When these occur at the level of an individual, it is known as avidya and when they occur at the level of a group or the world, it is known as maya. These concepts, propounded by the Vedantins, have found agreement even with Buddhist philosophers.

Indian philosophical schools have the distinction of elucidating the problem of truth and untruth by elevating it to the level of philosophy. One problem, however, has bothered me ever since I came of age. This had troubled me at a personal level when I wrote Saakshi (The Witness) a few years ago. The novel ends with the question, Lord, whats the root of untruth? Can it never be destroyed? Although this question marked the end of Saakshi as a novel, it didnt help assuage either my intuition or intellect. However, after I finished writing Aavarana, I feltand continue to feelthat this same problem of truth and untruth has assumed both social and national dimensions.

We cannot truly comprehend our own selves or the history of our nation or, indeed, the history of the entire world, unless we unshackle ourselves from the bonds of false knowledge, desire and action, and elevate the intellect to a state of detached observation.

~

I have no claim to originality as far the historical element in this novel is concerned. Every detail and behaviour of the characters described is backed by evidence and is an organ of the book without violating the boundaries of artistic freedom. Both creative writers and discerning readers will notice this aspect as the technique of the novel unfolds. The character who writes a novel within this novel provides the necessary historical evidence as a prerequisite to her writing. My only claim to originality is the form that I have given to it. If any literary merit has ensued in the backdrop of historical truth, I consider this novel to be a successful work of literature.

Anybody who embarks upon writing a historical work essentially needs to conduct concrete research to support even the tiniest detail. The authors responsibility is towards the historical truth of the subject on which his/her work is based. When truth and beauty are put on a scale, the writers fidelity must invariably be in favour of the truth. An author doesnt have the moral right to violate truth and take refuge in the claim that he/she is only a creative artist.

The reader, too, shares equal responsibility with the author in the quest for truth. He or she must comprehend the characters and situations in the light of objective truthboth factual and artistic. This sort of mental framework helps to actually savour the experience of reading a literary work, rather than getting agitated by reading it with personal prejudices in mind. We are not responsible for the mistakes committed by our previous generations. However, if we equate ourselves with them and regard ourselves as their heirs, we must then be ready to also share the responsibility for their mistakes. We wont attain maturity unless we cultivate the wisdom to discriminate which deeds of our ancestors we need to reject and which achievements we need to take inspiration from. If learning lessons from history is a mark of enlightenment, so is breaking free from it. This applies equally to every religion, caste, creed and group.

S.L. Bhyrappa

The cool evening breeze gently blew over Razias hair, fanning the strands in a caress as she sat looking out of the window. It wafted inside the room on the top floor of the government guest house that overlooked the Tungabhadra River and soothed her limbs, tired from the relentless, all-day wandering around Hampis ruins. Should I order tea? Amirs question was lost on her. He waited, unsure, when she didnt respond. Perhaps the breeze had drowned his voice, or she was just in one of her moods. And it wasnt the first time. He was familiar with her sudden, inexplicable silences. She was, like him, an artist, entitled to her quirks. But now the sight of the river undulating to the caress of the sundown breeze was markedly romantic. He had to talk. Do you have any idea how beautiful your hair looks, tinged by this twilight? You should have dyed it. The glow would be even lovelier! he said, his voice soft with love. She did not reply. The dye remark wasnt new. On several occasions in the past she had countered it with Im ready to dye my hair just the way you like it, but you need to dye your beard too. He had briefly considered it. A jet-black maulana beard would have posed no problem but his was the Marxist-intellectual variety, which needed weekly trimming at the hands of an expert. The hairstylist would anyway shear the dyed portion. On a man, white hair was a sign of attractiveness and accomplishment, even wisdom, but on women, it only meant old age. But she just didnt get his reasoning, and instead spoke about equal rights for men and women. Well, it was pointless to add anything further and risk raking up that old argument again.

The waiter who brought tea and biscuits awaited their order for dinner. She mumbled that she would be okay with whatever Amir ordered and stood up, teacup in hand, returning to the window, once again lost in her thoughts. This was completely unlike her. Whenever they went out, Razia typically took charge of the menu, carefully selecting the items to order. Amir spoke to the waiter, Chicken pulao if you have it, chicken biryani, if you dont.