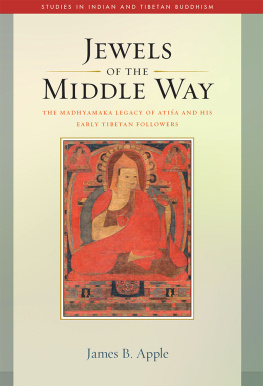

B UDDHIST TRADITIONS are heir to some of the most creative thinkers in world history. The Lives of the Masters series offers lively and reliable introductions to the lives, works, and legacies of key Buddhist teachers, philosophers, contemplatives, and writers. Each volume in the Lives series tells the story of an innovator who embodied the ideals of Buddhism, crafted a dynamic living tradition during his or her lifetime, and bequeathed a vibrant legacy of knowledge and practice to future generations.

Lives books rely on primary sources in the original languages to describe the extraordinary achievements of Buddhist thinkers and illuminate these achievements by vividly setting them within their historical contexts. Each volume offers a concise yet comprehensive summary of the masters life and an account of how they came to hold a central place in Buddhist traditions. Each contribution also contains a broad selection of the masters writings.

This series makes it possible for all readers to imagine Buddhist masters as deeply creative and inspired people whose work was animated by the rich complexity of their time and place and how these inspiring figures continue to engage our quest for knowledge and understanding today.

Preface

G ESH L HUNDUP S OPA (19232014) jovially introduced me to the life and teachings of Atia in the early summer of 1992 while I was on retreat at Deer Park Buddhist Center outside of Oregon, Wisconsin. Around the same time, I acquired a used copy of Phabongkhapas Liberation in the Palm of Your Hand from an old bookstore on State Street in Madison, Wisconsin, and read Atias life story in English as well.

When I returned to Indiana after the summer to finish my undergraduate degree at Indiana University, I worked during the 1992/3 academic year as a book shelver on the ninth floor of what was then Memorial Library. The ninth floor of the Memorial Library (now Herman B. Wells Library) at Indiana University has one of the largest collections of Tibetan books in North America. I would often look at the Tibetan books in between shifts of shelving regular bound books. One time while perusing Tibetan books, I spotted a Tibetan volume that was entitled Writings of Lord Atia on the Theory and Practice of the Graduated Path. After my summer retreat at Deer Park, I was excited to see a work by Atia, so I unpacked the bound volume and began to flip through the Tibetan folios. My initial excitement became disappointment as the text was in a difficult to read handwritten script, which I was not yet able to read. I carefully put the volume away and explored other Tibetan works. Now, over two decades later, I have translated the works in that volume of Atias writings, and a selection is found in chapter 12 for the first time in modern publication.

I returned to Wisconsin as a graduate student at the University of WisconsinMadison in the fall of 1994, and in the spring of 1996, Gesh Sopa led my graduate school classmates and I through Atias biography in a second-year classical Tibetan class. The following academic year we read Atias Open Basket of Jewels (excerpt in chapter 4).

I did not intend to research Atia, as I was interested in Tsongkhapa Losangdrakpa (13571419). When I landed a tenure-track position at the University of Calgary in 2008, and having published a book related to Tsongkhapa (Stairway to Nirva), the works of Izumi Miyazaki on Atia came to my attention. I immediately found my class notes from Gesh Sopas class, revised the English translation and annotation of Miyazakis paper, and published this in 2010 as Atias Open Basket of Jewels: A Middle Way Vision in Late Phase Indian Vajrayna. At the same time that I arrived at the University of Calgary, the availability of the Collected Works of the Kadampas, unknown to Tibetan scholars after the seventeenth century and published in fascimiles only recently, had been announced. Over the last ten years, I have focused on these manuscripts that contain the works and teachings of Atia and his early Kadampa followers.

Rather than a minor figure as some modern scholars might portray him, Atia emerges as a fully trained and well-educated Buddhist master who was subtle in thought and cagey in action. The Tibetans at the time were seeking an authoritative Indian teacher to revitalize the dharma in West Tibet. In coming to Tibet, Atia was a great Indian Buddhist master who fulfilled, and in a number of ways even exceeded, the expectations of the Tibetans.

In the study of Indian and Tibetan Buddhism, it is often said that the study of Sanskrit and classical Tibetan is like the sun and the moon. The two languages complement each other in the study of Indian Buddhist texts, reflecting the light of understanding. However, in preserved writings of the life and teachings of Atia, the scholar currently only has access to the Tibetan side of the story. As there are currently no surviving, or at least accessible, Indian manuscripts of Atias writings or accounts of his life, the Indian side of the story is not represented in Sanskrit or Old Bengali. Scholars cannot even be sure of the underlying meaning of his nickname, Atia. So, the reader should be aware that the life and teachings of Atia are in some ways filtered by the Tibetan accounts of his life and the Tibetan translations of his teachings.

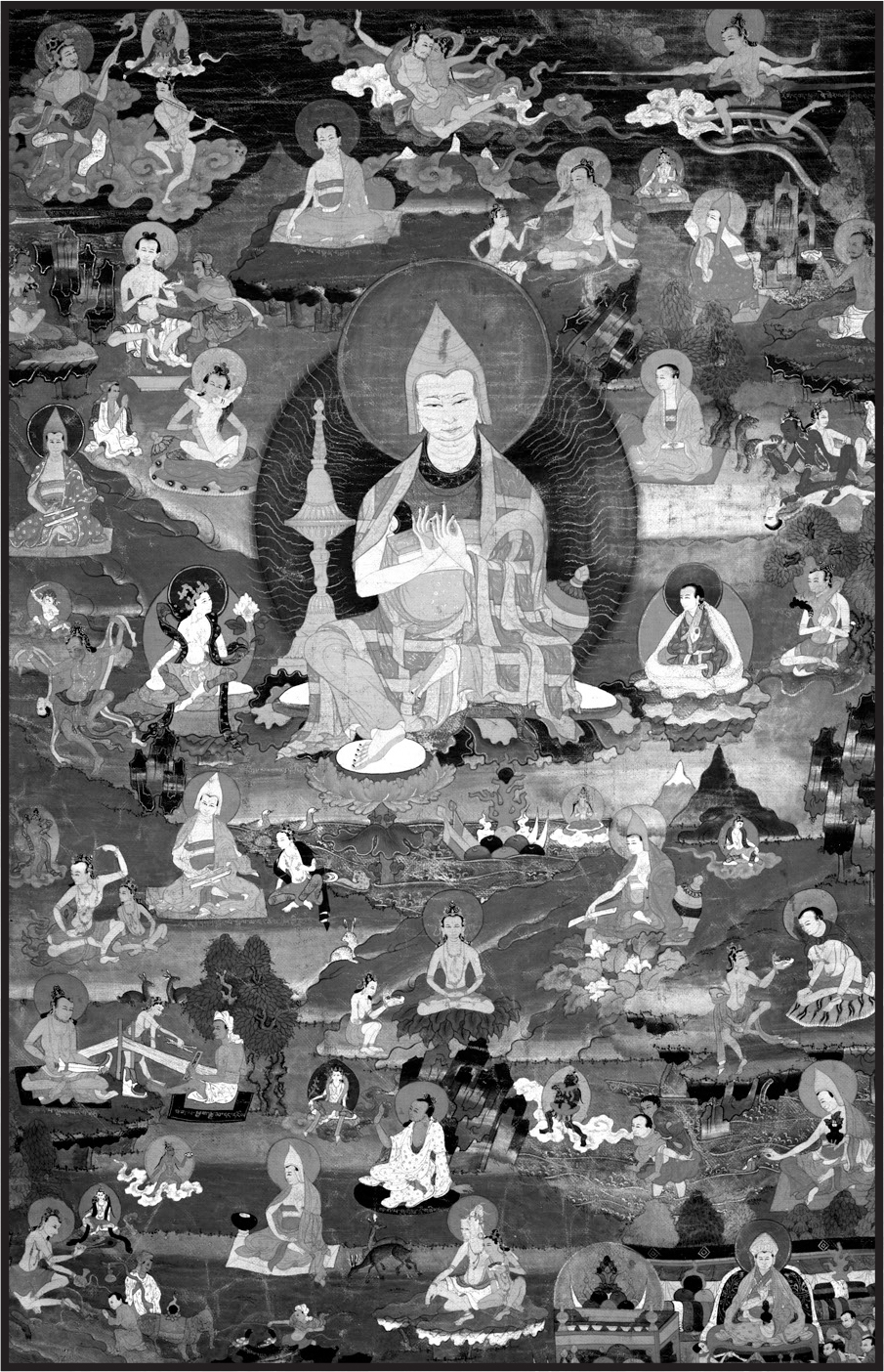

Atias life and teachings are a Tibetan story, and what an amazing story it is. Atias life is guided by dreams, visions, and predictions from buddhas and bodhisattvas, including the savioress Tr. In the story of Atias life, we enter a world of gold, sailing ships, palm-leaf manuscripts, and mantras, rather than credit cards, automobiles, social media, and cell phones. The story involves transactions in over two million dollars worth of gold and travels throughout maritime Buddhist Asia. The Tibetans have faithfully preserved what is known of Atia Dpakararjna, the vicissitudes of his life, the struggles in his travels, and the spirit and meaning of his teachings.