Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

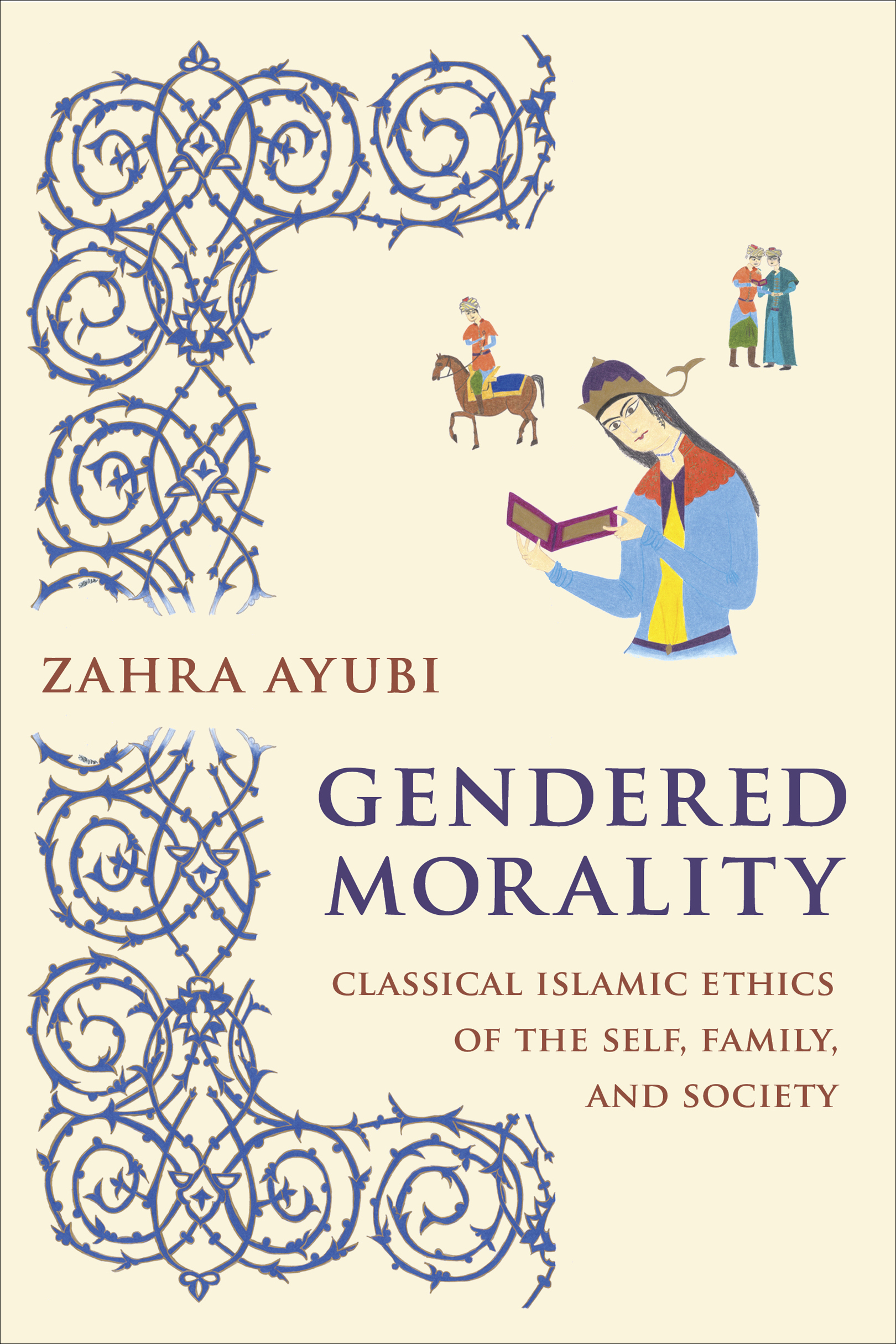

GENDERED MORALITY

Gendered Morality

Classical Islamic Ethics of the Self, Family, and Society

Zahra Ayubi

Columbia University Press New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2019 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54934-9

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Ayubi, Zahra, author.

Title: Gendered morality : classical Islamic ethics of the self, family, and society / Zahra Ayubi.

Description: New York : Columbia University Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018048958| ISBN 9780231191326 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780231191333 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Sex roleReligious aspectsIslam. | FemininityReligious aspectsIslam. | MasculinityReligious aspectsIslam. | MarriageReligious aspectsIslam. | Social ethicsReligious aspectsIslam. | IslamSocial aspects. | Islamic philosophy. | Religion and social status.

Classification: LCC BP134.S49 A98 2019 | DDC 297.5081dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018048958

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover image: Zahra Ayubi. Objection , color pencil drawing.

To my husband and our children,

with a prayer that we find our saadat

Contents

FIGURES

TABLES

Bism Allah ar-Rahman ar-Rahim.

My deepest gratitude goes to those who took on my share of family responsibilities, took care of me, and thus enabled me to write this book: my husband, my mother, my mother-in-law, my niece, my father, and the director and teachers at DCCCC. My gratitude then goes to my late father in law, who was fond of the Kimiya-i Saadat and the Akhlaq-i Nasiri . He introduced me to the classical world of akhlaq in the brief time that I spent with him before his passing.

While researching and writing that earliest version of this project at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, I greatly benefited from the mentorship of Kecia Ali, Carl Ernst, Juliane Hammer, Omid Safi, Randall Styers, Bruce Lawrence, and Ebrahim Moosa. Since then, I was able to strengthen this projects contribution thanks to many fruitful conversations with generous colleagues and peer and senior mentors. In particular, Kecia Ali modeled scholarly mentorship for me when she generously commented on multiple drafts and pushed my thinking each time. Several scholars helped me crystalize this books argument through their feedback on parts or all of it at conferences, writing workshops, or lunch meetings: Jamie Schillinger, Travis Zadeh, Kathryn Kueny, Mary-Jane Rubenstein, Dhananjay Jagannathan, Laura McTighe, Holly Shaffer, Laury Silvers, Zayn Kassam, Etin Anwar, and Danielle Widmann Abraham. Thanks also to Aysha Hidayatullah, Amanullah De Sondy, Fatima Seedat, Ilyse Morgenstein Fuerst, and Saadia Yacub for our discussions at conferences about our respective projects. Thanks also to friends who served as writing partners at various points: Lilu Jessica Chen, Rose Aslan, Nisha Komattam, and Farah Zeb.

At Dartmouth, thanks to my religion department colleagues Susannah Heschel, Devin Singh, and Kevin Reinhart, who read drafts of some of the chapters, and the rest of the religion department colleagues for their feedback at a faculty research colloquium. And thanks to religion department administrators Meredyth Morley and Marcia Welsh. I appreciate my students, in particular Iman AbdoulKarim, who read versions of chapters from this book and always engaged me in thoughtful conversation about them. I am grateful to my research assistant, Jessica Kocan, who swooped in to help with library sources and citations. I would also like to acknowledge the support of Imam Khalil Abdullah and Rabbi Davin Litwin at the Tucker Center, Cristen Brooks at the Womens, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Program, and the Ethics Institute at Dartmouth College.

Thanks to Olga Davidson for introducing me to the richness of the Persian context of feminist inquiry. Thanks to Eric Goodson for teaching me to reexamine conventional historical narrative and Alexandra Siemon for introducing me to the academic study of Islam. Special thanks to Islamic art history professor Glaire Anderson and tezhip artist Zuhal Karamanli, who taught me how to appreciate the fine elements of miniature paintings. Thanks to my various studio art teachers, especially Jim Misner, Suzette Jones, and Gene Scattergood, who helped me develop the skills that ultimately enabled me to create the cover art for this book.

Sincere gratitude goes to my beloved mentor in memoriam, the late Tayyibah Taylor, who celebrated my scholarly pursuits, reminded me to remain humble in sharing my knowledge, and demonstrated to me how to be a strong yet spiritual Muslim woman. Although she was not a scholar, she was among the most learned and wise women I have ever known. Another tribute goes to my late uncle, Dr. Zobair Ayubi, who expressed great understanding and encouragement for my scholarly pursuits. I wish they had both lived to see this books publication.

Finally, I dedicate this book to my husband and children. We have many privileges, but we are simultaneously oppressed along many planes of our individual and collective identities. We have a claim on flourishing, and I pray that we can achieve it.

In the climactic scene of the dramatized documentary al-Ghazali: The Alchemist of Happiness (2004), the eponymous twelfth-century jurist, theologian, mystic, and ethicist stands with his family in the street outside their Baghdad home, a few simple possessions strapped to his donkeys back. He is preparing to take leave of his wife and two children, perhaps permanently. Up to this point in the film, director Ovidio Abdul Latif Salazar presents a dramatic recounting of Ghazalis illustrious career in Baghdad, tracing his increasing disillusionment with the citys corrupt political climate. Ghazalis departure marks the culmination of his crisis of faith and conscience. Throughout the film, he is depicted as a troubled genius, contemplative about the nature of true happiness, living out his public life against a backdrop of domesticity. His beautiful wife and his young son and daughter appear in the film intermittently, though always silent. In this climatic farewell scene, partly based on a passage in Ghazalis autobiography, he has resolved to embark on a long journey to Damascus, Jerusalem, and Makkah. He embraces each of his children and pauses briefly to glance at his wife. Without speaking a word to her, he then turns toward his brother and says, You understand that I have to leave. The third item in Nasrs list of Ghazalis lofty sacrificeshis familyremains curiously submerged from our attention throughout the film.

Ghazalis wife, played by famous Iranian actress Mitra Hajjar, appears several times over the course of the film. She is shown praying at home, receiving visits from Ghazalis doctors, and delivering and picking up trays of food for Ghazali. Yet the filmmakers do not give her a single line of dialogue, as though such an omission were necessary in order to stay true to Ghazalis biographies, which do indeed omit mentions of his wife. Whatever the reason for such a flattened depiction of Ghazalis wife, her near-erasure from the films climactic departure scene is striking. But what, precisely, is being erased? What might Ghazalis wife have said to him when he left? Did he ever have a private conversation with her about his planned journey? Did she ask when she could expect him back at home in Tus, or how she should rear the children and run the home in his absence, or what she should do in case of his death? What, more broadly, was her role in Ghazalis intellectual and spiritual pursuits? What were her own spiritual goals? The film does not raise these questions, much less answer them.