G. P. P UTNAM S S ONS

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

First published by Bonnier Books U.K.

Penguin is committed to publishing works of quality and integrity. In that spirit, we are proud to offer this book to our readers; however, the story, experiences, and the words are the authors alone.

I dedicate this book to my dearest grandmother, Vera May Tiley (ne Gow), who gave me much love, and taught me how to be brave in the face of adversity.

CHAPTER 1

Beginnings

Imagine, for a moment, that you are walking in a winter wood. The ground is soft beneath your feet; something catches your eyesomething untoward, something not quite natural, in a depression just off the beaten track. Perhaps you are here walking your dog (this is the way so many stories start). Perhaps the dog hurtles off into the undergrowth and whines. As you fight through the brambles to reach it, you have a moment of forebodingand, looking down, you realize why... for there in front of you where the dog has frantically scraped the soil, the lifeless hand of a body is exposed, its pallor stark against the black humus.

It was not so very long ago that identifying the culprit in a crime like this might have been possible only by the testimony of witnesses or the confessions of the accused. Within living memory, and in the absence of any clues to its identity or to connect it to a potential suspect, a body discovered in a shallow grave might have remained a mystery forever. But times move on. The world of forensic detection gathers pace.

We are all familiar with the idea of fingerprints, and they have even been found in prehistoric pottery. The ancient Chinese and Assyrians used fingerprints to establish ownership of clay artifacts and, later on, documents. Sir William Herschel insisted on having fingerprints as well as signatures on civil contracts when he was a British administrator in India in 1858. Fingerprint analysis was firmly established by the late nineteenth century and, in 1882, Alphonse Bertillon, a French anthropologist, was routinely recording fingerprints on cards in his academic research into variation in people and, by 1891, the Argentine police had started fingerprinting criminals. The field developed apace and, in 1911, fingerprinting became accepted by the US courts as a reliable method of identifying individuals. Fast forward to 1980 to the first computerized database of fingerprints, NAFIS (National Automated Fingerprint Identification System), established in the United Kingdom and the United States.

In the 1990s, another quantum leap was taken in forensic detection with the development of DNA profiling. This, like fingerprinting before it, enabled the unique imprint of an individual to be captured but by taking samples of blood, semen, body cells, or roots of hairs. This development transformed the world of forensic detection, making identifying unknown victims, like our body in the winter wood, or connecting a person to a crime scene, much easier. Make no mistake about it, these were seismic moments in the history of forensic detection. Murderers who might otherwise have gone free have been imprisoned because of these advances. Rapists who would have gone on to rape again were caught and put behind bars. So too were innocent parties exonerated for the crimes of which they had been unjustly accused. Step by step, and with plenty of backslides along the way, police work got closer to the truth.

Fingerprints are not always found at a crime scene, especially if that crime is being perpetrated by somebody who is forensically aware and wears gloves, or covers their tracks behind them. And neither is DNA evidence as omnipotent or omnipresent as many people think; there might be no trace at all of an offender left behind at a crime sceneno hair, blood or semen, nor any other body fluids or tissuesso that building up a genetic profile of an assailant is just not possible.

Yet... what if there was another way to connect people and places, to exonerate the innocent and indicate somebodys guilt? What if, aside from fingerprint and DNA evidence, there were other traces left on us that could corroborate one version of events over another? And what if it was so pervasive that, no matter how forensically aware a criminal was, they could never quite shake it off?

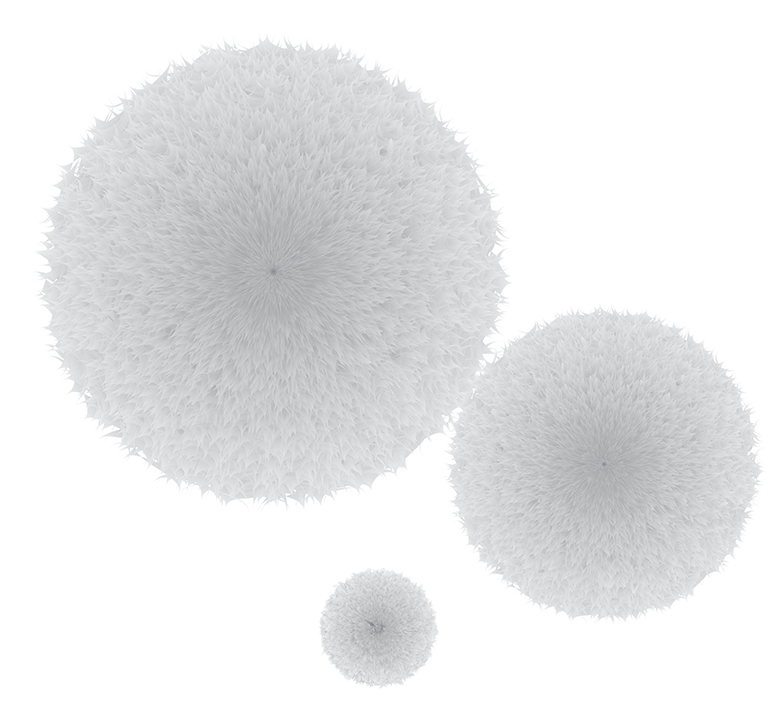

Imagine, again, that you are back in that winter wood. As you push through the brambles and overhanging branches to reach the body, the sleeve of your coat rubs up against an oak tree, collecting the microscopic spores and pollen that have become impacted in the crevices of the bark. As you scramble down the slope, your boots collect soil smears and crumbs in which are locked the pollen and spores that rained down on this patch of woodland recently, as well as in past seasons. That soil will also contain the multitude of living things that have made the soil their home, or fragments of the dead things that lived there before.

As you crouch down to make sure of your discovery, your hair brushes past twigs and leaves hanging over the body, picking up whatever pollen, spores, and other microscopic material have fallen onto their surfaces. Your traces on the landscapethe footprints you leave behind, the hairs and fibers you shedmight be easily obscured or overlooked. But what about the imprint the landscape has left on you? What if someone was able to retrieve and identify those microscopic traces, and visualize that place, or another even further afield, from the imprint it has left on your body and clothes?

Now imagine you are the killer. What traces of the landscape where you left your victim are you carrying with you, unwittingly, wherever you go?

This is where I come in, and where my own story dovetails with the history of forensic detection. In 1994, I was an environmental archeologist at University College London. Then, things changed.

It has been nearly fifty years since I began formally studying the world of plants, though the truth is, my love affair with the natural world reaches back much further. Even as a little girl, no matter how much I read about the natural world, I always wanted to know more. There is always so much more to be had; it is still the same for me now. This is frustrating because you can never reach the summit. Nobody can. The climb is grindingly hard, and it continues forever.