The ragama Stra With Excerpts from the Commentary by the Venerable Master Hsan Hua

On Respecting Sacred Books

In the Buddhist tradition, sutras are understood to contain the teachings of Buddhas and greatly enlightened masters. As guidebooks to the path to awakening, sutras are treated with reverence. It is customary to keep sutra volumes in a clean place, either above or apart from secular works; to handle them with respect; and to read them only while sitting upright or standing.

The ragama Stra.

Newly translated from the Chinese by the ragama Stra Translation Committee of the Buddhist Text Translation Society: Rev. Bhiku Heng Sure (certifier); Bhiku Jin Yan, Bhiku Jin Yong, Novice Jin Jing, Novice Jin Hai, Ron Epstein, David Rounds, Joey Wei, Fulin Chang, and Laura Lin.

Copyright 2009 by the Buddhist Text Translation Society. All Rights Reserved.

The Buddhist Text Translation Society is an affiliate of the Dharma Realm Buddhist Association, 4951 Bodhi Way, Ukiah, California 95482 (707) 462-0939, bttsonline.org.

| ISBN | 978-0-88139-962-2 (hardcover) |

| 978-1-60103-017-7 (ebook) |

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in Publication Data:

Tripitaka. Sutrapitaka. Surangamasutra. English.

The Surangama sutra : a new translation / with excerpts from the commentary by the venerable master Hsan Hua.

p. cm. Translated from Chinese originally written in Sanskrit.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

I. Hsan Hua, 1918-1995. II. Buddhist Text Translation Society. III. Title.

BQ2122.E5B84 2009

294.3'85--dc22

2009002694

09 10 11 12 13 / 5 4 3 2 1

Printed in the United States of America.

Table of Contents

The Buddha kyamuni in meditation posture, Gal Vihara, Polonnaruwa, Sri Lanka, twelfth century. Photograph copyright by John C. and Susan L. Huntington, reprinted by permission of the Huntington Archive of Buddhist and Related Art.

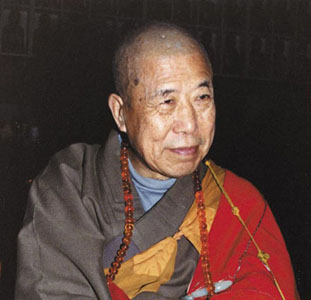

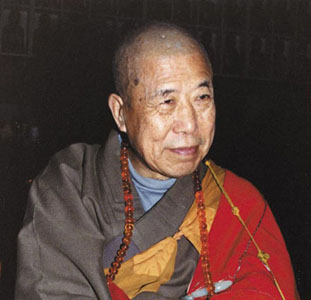

The Venerable Master Hsan Hua on the occasion of kyamuni Buddha's Birthday, in the Buddha-Hall at the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas, Talmage, California, May 1990. Photo courtesy of Soohoong Liung.

The Thousand-Hand Thousand-Eye Bodhsattva Who Hears the Cries of the World, at the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas, Talmage, California. Camphor wood, twentieth century. Photo courtesy Dharma Realm Buddhist Association archive.

A Buddhist disciple kneeling, probably the Venerable nanda. Lacquer on wood, Burmese, nineteenth century. Photo by Christian Maillard

Acknowledgements

The members of the ragama Stra Translation Committee would like to gratefully acknowledge with special thanks the important work of Bhiku Heng Chih, who was the primary translator for the Buddhist Text Translation Society's first edition of this Sutra. Her translation opened the way for this new translation and made the task much easier than it would otherwise have been.

We would like further to thank Bhiku Heng Yin, Madalena Lew, Martin Verhoeven, and Doug Powers for their advice; Bhiku Jin Xiang for proofreading the Sanskrit; Anne Cheng for her work in assuring the publication of this book; Stan Shoptaugh for book design; Laura Lin for copyediting; Dennis Crean for book and cover design, pagemaking, copyediting, and advice; Roger Kellerman and Susan Rounds for proofreading; Ruby Grad for indexing; and Mark Vahrenwald for his rendering of the Wheel of Dharma.

Foreword

When Tripitaka Master Hsan Hua moved to San Francisco to teach the Dharma to Westerners, his first project was to explain the ragama Stra in detail. During the summer of 1968, he convened a ninety-day meditation retreat that focused not only on meditation but also on the ragama Stra.

Beginning in 1980, the Buddhist Text Translation Society published Master Hua's lectures from that summer session, and for the first time a complete Mahyna meditation manual was available to Western readers. Earlier English translations of the ragama were incomplete and often came without explanation. Master Hua's presentation placed the Sutra at the heart of the contemplative life, thereby opening a road into actual cultivation of the Dharma for those who desired to follow the Buddha's path. From Master Hua's perspective, the ragama is not obscure or intimidating, nor is it lofty beyond reach. He explained the text as a kalynamtra, a good and wise spiritual friend. He was not alone in doing so. Throughout the centuries in China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam, meditation teachers and monks such as Master Han Shan of the Ming Dynasty, Master Yuanying of the Republic era, and Master Hua's own teacher Master Xuyun respected and endorsed the ragama Stra's instructions and used the Sutra as a reliable yardstick of proper samdhi.

Over the years, when I have need advice in cultivation, I have referred to the ragama Stra for authoritative information. I go to the Fifty Demonic States of Mind (part 10) to check on strange states in meditation. I go to the Twenty-Five Sages (part 6) for encouragement on the path from the voices of Bodhisattvas. I go to the Four Clear and Definitive Instructions on Purity (part 7) for clarity on interaction with the world; for example, there I find the Buddha's reasons for advocating a harmless, plant-based diet.

In carrying on the perspective of the past, Master Hua emphasized the real-life interaction between the Buddha and his students. I am drawn to the Buddha's voice as it appears in the Sutra. His tone is at all times both wise and kind. For example, a noble king converses with the Buddha about his childhood alongside the Ganges River. After answering the Buddha's skillful questions, the king experiences the serenity of his intrinsic nature and loses his fear of death.

The king hears the Dharma and gradually understands; but even before that conversation, a young courtesan meets the Buddha and immediately wakes up. She has fallen in love with nanda, but upon hearing the Dharma, she adjusts her priorities, abandons the pursuit of pleasure, and discovers samdhi and wisdom. She becomes an Arhat on the spot, before Ananda does. Her story illustrates the lack of gender or class bias in the Buddha's teaching as found in Mahyna sutras.

In the dialogue between the Buddha and his cousin nanda, we find the framework of the narrative and the full expression of the Buddha's range of teaching skills. The Buddha patiently guides nanda through the landscape of his mind as he progresses from book-learning to actual experience.

The Buddha's teaching in the Sutra came alive for me because at Gold Mountain Monastery as a young monk, I observed Master Hua respond with the same measure of unerring kindness to the variety of faithful Chinese devotees, university professors, and truth-seeking hippies who passed through the door of the monastery. Each received the appropriate measure of Dharma-water to nourish their bodhi sprouts.

The Buddha kyamuni in meditation posture, Gal Vihara, Polonnaruwa, Sri Lanka, twelfth century. Photograph copyright by John C. and Susan L. Huntington, reprinted by permission of the Huntington Archive of Buddhist and Related Art.

The Buddha kyamuni in meditation posture, Gal Vihara, Polonnaruwa, Sri Lanka, twelfth century. Photograph copyright by John C. and Susan L. Huntington, reprinted by permission of the Huntington Archive of Buddhist and Related Art. The Venerable Master Hsan Hua on the occasion of kyamuni Buddha's Birthday, in the Buddha-Hall at the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas, Talmage, California, May 1990. Photo courtesy of Soohoong Liung.

The Venerable Master Hsan Hua on the occasion of kyamuni Buddha's Birthday, in the Buddha-Hall at the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas, Talmage, California, May 1990. Photo courtesy of Soohoong Liung. The Thousand-Hand Thousand-Eye Bodhsattva Who Hears the Cries of the World, at the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas, Talmage, California. Camphor wood, twentieth century. Photo courtesy Dharma Realm Buddhist Association archive.

The Thousand-Hand Thousand-Eye Bodhsattva Who Hears the Cries of the World, at the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas, Talmage, California. Camphor wood, twentieth century. Photo courtesy Dharma Realm Buddhist Association archive. A Buddhist disciple kneeling, probably the Venerable nanda. Lacquer on wood, Burmese, nineteenth century. Photo by Christian Maillard

A Buddhist disciple kneeling, probably the Venerable nanda. Lacquer on wood, Burmese, nineteenth century. Photo by Christian Maillard